Gudetama is the Bartleby of the emoji. An egg yolk that is an ode to idleness and to the maxim “I would prefer not to”. Víctor Navarro Remesal introduces you to this Japanese phenomenon.

FILMS WITH STRINGS AND PUPAPHOBIA

Michael Redgrave, ventriloquist in Dead of Night, with his horrible and incontrollable dummy.

Who’s the scariest, the Muppets or the Guardian of the Crypt?

I suspect we have no more puppet films for the same reason for which Di Caprio won the Oscar imitating Bear Grylls or Jared Leto stalked his film colleagues to play the Joker: for our obsession with authenticity. That’s my first hypothesis. The myth of the method and of a badly-understood naturalism make us want everything to look real even in the making of, and that leaves no room for a doll being fidgeted by someone off-screen. And yes, I know that a great part of the campaign of The Force Awakens was based on the fact that they were retrieving the rubber dolls, but there the Muppet argument was defended because they looked realer than their digital versions. What I’m wondering here is whether there could be puppet films and not films with puppets, a filmography defined by its fearless exhibition of string puppets or hand dolls being animated live. The type of films that, except from the hundredth Muppet incarnation or rarities such as Danish Strings, have no stable production, distribution space or devoted audience. Its own definition is tricky: when the Seattle International Film Festival gave the Great Jury Animation Prize 2015 to The Mill at Calder’s End, the animator Tess Martin (author of The Lost Mariner, an adaptation of an Oliver Sacks text) made it to the headlines with her blunt declaration: Puppetry is not animation. Then, what is it? And what makes it so difficult to define?

The first puppet in the history of film already faced us with our bodily mechanics.

Puppet films are little consumed and discussed, and when they are it’s because of their artistry, as a courtesy to tradition: should we see them not as a minority, we would judge them differently. It seems that in the genealogy of representation we have left them behind, like we have done with the zoetrope, silhouettes or magic lanterns. Puppets seem old-fashioned, clumsy, and primitive; their movement is lively but a lot more limited than computer generated animation or stop motion. They require us to use a different concept of authenticity, maybe a Brechtian one: they undeniably exist before the camera, but are pure artifice, an artifice that isn’t hidden (in bunraku, each puppet is animated by several visible operators), and this is different from the usual film trick (in which the strings are erased in post-production), and probably incompatible with it. Puppets make no sense in films that only conceive them as ancient. It’s a good explanation, practical and reasonable, but I have yet another one: they are too disturbing.

The first proof of this comes to us through, obviously, horror movies. There’s a certain expression of emptiness on the faces of dolls, something inhuman in their movements, which the genre has exploited for decades. Apart from Chucky, we have the killing figurine of Trilogy of Terror or the recent and dull Annabelle; also, dummies that torture their ventriloquists in a couple of episodes of The Twilight Zone and in no less than five films, from The Great Gabbo by Erich von Stroheim to Magic by Richard Attenborough; and, indeed, killer puppets in the saga Puppet Master, with which the producer Charles Band, saint patron of video clubs, has been developing his career since 1989. The funniest thing is that most of them use, almost at all times, stop motion or animatronics, and very rarely move their monsters with strings. Horror with puppets, but which at the same time doesn’t use them as such.

The killer doll is a recurrent trope in modern fiction, and I sense there must be a specific phobia behind it. A quick search confirms this: ‘pupaphobia’ or fear of puppets, which is contained within the automatonophobia or fear of everything that looks like a human being (such as automatons, wax statues or mannequins). I don’t like inventing theories in hand (a way of imposing normativity through diagnostics), but the thing makes sense and fits in with the much talked about concept of the ‘uncanny valley’ that robotics professor Masahiro Mori proposed in 1970: the more the robot (or any artificial figure) looks like a human, the more we will look at what makes us different from it and, in consequence, the more scary we will find it.

There we have, thus, the key to this: puppets are sinister, Jentsch and Freud’s Unheimliche, something strangely familiar and at the same time inconceivable, and provoke a difficult to pinpoint repulsion. Horror films about puppets are a symptom of this, but the sinister thing is at the root of it all: any puppet makes us feel uneasy, even those in Team America and Spitting Image. In fact, the Parker and Stone comedy is constantly drawing from that uneasiness to create gags drawing from its intimate moments or a circus sex scene. Seen this way, it’s no strange to consider The Dancing Skeleton, a very brief short-film dating from 1897 in which the brothers Lumière shot the puppet of a skeleton that disassembled and assembled itself again while dancing, as the first puppet film. Not to talk about how terrifying some of Jim Henson’s creations can be, such as those in The Dark Crystal, Labyrinth or even Fraggle Rock, or the creepiest puppet ever, the guard animated by American puppeteer Van Snowden in the series Tales from the Crypt.

Some of the delirious puppets in the Puppet Master saga.

In Strings, strings are integrated in the fictional world as mysterious (and Schopenhauer-style) sources of life.

I will go even further: puppets are sinister because they miss something to be like us, but also because they make us think that we, at the same time, are missing something. Heinrich Von Kleist explains that he attended a punch and judy show with a famous dancer, who honestly admired them and argued that dolls could dance better than any human, since they would “never do anything affected.” For Heinrich von Kleist, puppets were also free of “consciousness disorders,” and Barthes saw bunraku as the incarnation of an ideal clarity, swiftness and subtlety. The mechanisms articulating the puppet, Benjamin goes on, depurate their movement and prevent the operator from making any mistakes in the line that takes to the “path to the soul of the dancer”; thus, it can reach pure grace, presented “in the human figure that has no conscience whatsoever, or has an infinite one, in the action doll or in God.” It’s as if we suspected that, although operated by a master of puppets, in the string going from finger to figure there was some force we couldn’t grasp, and we can’t access it because we ourselves are the obstacle: Barthes said that bunraku didn’t imitate actors, but got rid of them.

There enters the picture reasoning over metaphysical and phantasmagorical questions. What moves the doll, really? Where has that life it seems to have arisen from? Again, horror stories present toys possessed by demons, psychopaths or sorrowful souls. It’s dual anthropology taken so far that it becomes a nightmare: nothing distinguishes our body from a puppet’s, and if we’re flesh and blood puppets, how to be sure that we have control over the strings? In Kitano’s Dolls, the apathetic faces of the puppeteers contrast with the liveliness of artificial figures. Writer Zadie Smith talks about the eyes of the puppets (animated, though, with stop motion) in Anomalisa as , a reference to Schopenhauer and his idea of a vital force permeating everything that pushes us to live. For Schopenhauer, human beings are “puppets set in motion by an internal clock”, by a will that acts as a puppeteer without us noticing. Smith highlights that the Anomalisa dolls are clearly artificial except for those realistic and detailed eyes: they turn them into a new type of puppets that “can see, feel pain, suffer!”, that is, into us?

For that reason, and although I buy the first hypothesis of a cultural development that rejects them, I think puppets have not earned a place in film because they make us feel uneasy, an uneasiness that has less to do with irrational phobias and DSM traumas and more about suspicion of our own existence: we’re so terrified of them being human as of us being puppets, missing something to explain our own movement. When we face a puppet dancing, I suspect we fear it will make us understand the well-known sentence Doctor Manhattan utters in Watchmen: “we’re all puppets, but I can see the strings.”

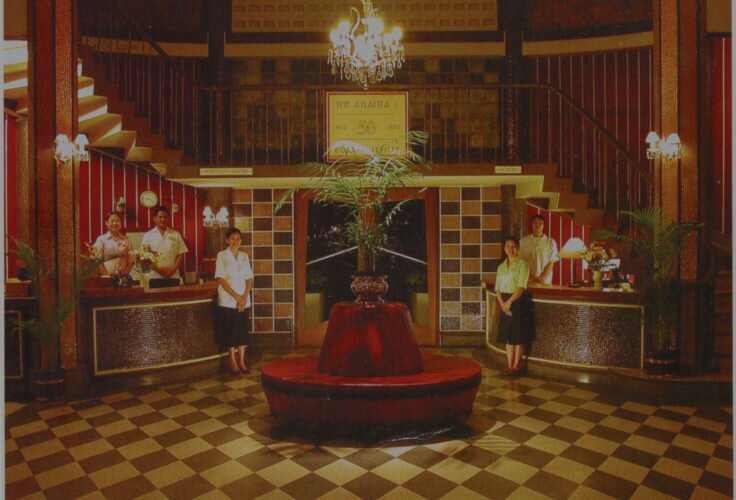

Hong-Kong series Pili combines hand puppets with martial arts.

The skeksis and gelflings from The Dark Crystal: all able to scare you senseless.

The wuxia puppet goes on in The Arti: The Adventure Begins.

The orthopaedic puppets of Team America are the worst possible action heroes.

In Dolls, Kitano pays homage to bunraku by humanising his puppets.