Musicians who don’t want to show their faces: shyness, mystery and anonymous ethics. Gerard Casau unmasks the Salingers of music.

Mise-en-scène

*

*

01. Raúl Castro: centrality, references and noble wood

By Gerard

Casau

On the 25th of November, 2016, the evening broadcast of Cuban television was interrupted by the sudden appearance of the president of the Consejo de Estado y de Ministros, Raúl Castro, who appeared to inform the nation of the decease of Fidel Castro, his predecessor and brother (although this family link was excluded from the official speech). The scene showed Castro in an office with wooden walls that created an almost monochrome brown set, surrounded by photographs and portraits of famous people in the history of Cuba, like the “apostle” José Martí Pérez, which was hanging on top of his head. We are still unaware of the preparation of this emergency shooting, but be it accidental or planned, the composition showed Raúl Castro belittled almost to a ridiculous point, like an old child crushed by circumstances and by the History around him, confirming the version of those media who have wanted to see him as a secondary, or transition, actor in the future of Cuba.

In a season marked by the disappearance of many 20th century icons, the death of the Cuban Revolution Chief Commander seemed a logical event (as was, obviously, due to his nonagenarian condition), but the way in which his decease was announced was quite surprising: after years of speculations around his health, disclaimed time and time again through images of him in colourful tracksuits, his death came suddenly and in a seemingly natural way, without the previous noise and morbid countdown that accompanies the agony of some celebrities. We found out we should start talking about Fidel Castro in the past tense through the State’s communication means, with an Official and rigorous message. In this decade, only the death of Kim Jong-il possessed similar characteristics; even if between the two broadcastings there are several details that make them different. Before the briefness and vigorously anti-sentimental tone of the Castro announcement (even more shocking should we bear in mind the brotherly blood link uniting deceased and messenger), the Korean Central Television used a forest background for the crying presenter Ri Chun-hee (the same that communicated the death of Kim Il-sung in 1994) to tell the people that the moment to shed tears for their beloved leader had come. Between sobs, Ri rigorously told the list of ranks Kim Jong-il accumulated –as if the speech tried to delay the demise as much as possible– to, finally, affirm that he had suffered from a “sudden illness” that caused death in a train while he conducted one of his . The message finished with a transfer of powers that linked the future of the nation to its new leader, Kim Jong-un.

*

*

02. Ri Chun-hee: tears from the forest

As paradoxical as it may seem, this kind of funeral communications represent the ultimate triumph of power since through them it manages to even control such an invincible event as death, channelling it in the way the System finds best.

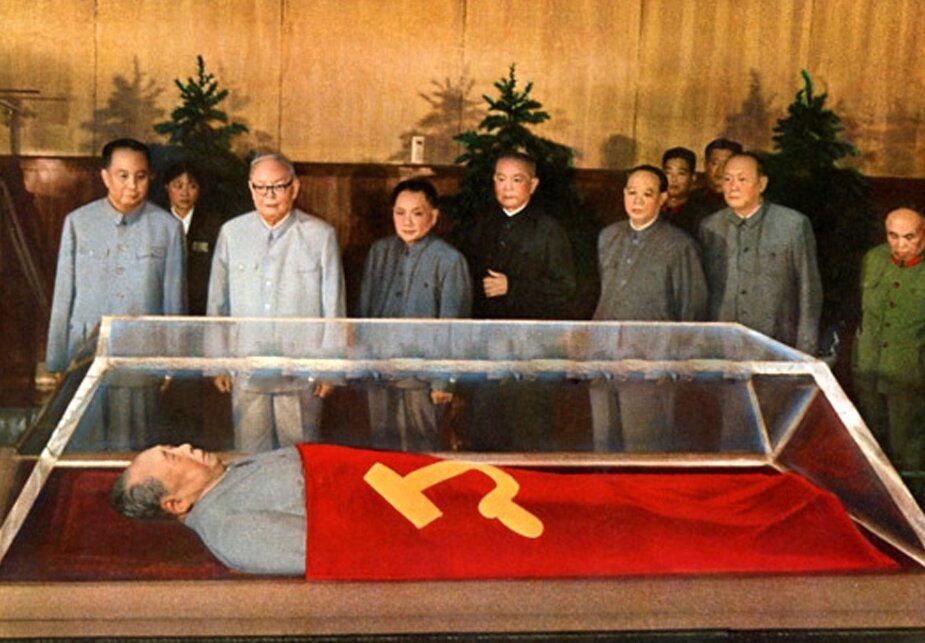

And making sure, on top of the existence of a corpse, although not young and beautiful, admirable and, in some instances, as miraculously incorruptible as a wax statue. The former can also work the other way around when the government uses the breaking news chyron to proclaim the victorious death of an enemy. Obama did so with Bin Laden, in a discourse that quickly announced the news to soon after lyrically evoke September 11th and its dramatic consequences (“an empty chair at the table,” “parents who will never know their children’s embraces”). In this case, and far from casually, the White House made sure that the body of the nemesis disappeared from the face of the Earth, denying him an image.

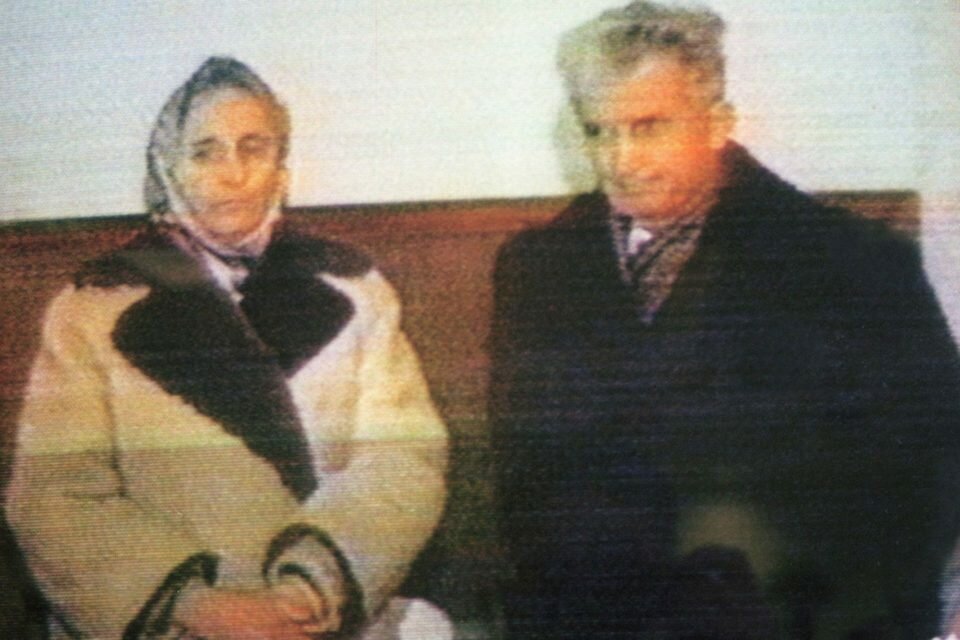

If we say that high rank death statements seem a rarity is because, in good measure, the media have accustomed us to witness the death of power through indignity: from the photographs showing Mussolini’s corpse, corrupted, beaten up and hanging upside down, to the digital, nervous and low-fi videos that captured the last instances of the life of Saddam Hussein and Muammar al-Gaddafi, we see a literal snatching of power that dirties the portrait of those straps that had their statues made. Among all these instants, none is as shocking as the long trial and subsequent execution of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu, on Christmas day 1989. In an enclosed and miserable space, we see a military jury determined to condemn the Romanian dictator and his wife. The clothes, the lighting, the room… it all transmits an improvised feeling of cold and dampness that turns into pathetic anger when the couple protest, aloof, facing their judges and executioners and requesting not to have their hands tied (a moment in which the camera reveals a will not so much of a neutral registration of the event as of humiliating inquisition, zooming in to reveal their tied extremities), to later on directly cut to the infamous image of the executed corpses. This event inspired Chris Marker to create a caustic piece, Détour Ceausescu, that remixed the document to reveal its condition of media show, including commercial breaks.

04. The blurry last minutes of the Ceausescus

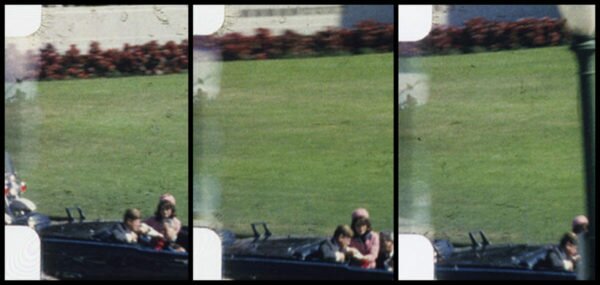

05. The Zapruder film: death recorded live

In all these cases, the hand that held the wise camera knew (or, at least, sensed) the destiny of the protagonists. But the political death that has acquired the most notoriety was captured in an amateur and accidental way. I’m talking about, of course, of the Zapruder Film, a few seconds of celluloid that register the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas, turning a home video into a piece of History, susceptible of being edited, manipulated, restored and observed from all the possible angles that the conspiranoid theory allows, so much so that it can be hoisted as much by an anonymous blogger from his basement of the deep web as by Oliver Stone, who gave the Hollywood stamp to the counter history by obsessively inserting in his JFK the frame in which Kennedy’s head fatally explodes. In a less solemn (or directly iconoclastic) style, John Waters also referred to Zapruder’s film in one of his first medium-length films, Eat Your Makeup, which reproduced the fatal sequence with Divine as Jacqueline Kennedy.

Despite the abyss of intentions that separate Stone from Waters, both filmmakers perfectly understood that a political corpse is never a mere dead body, but one that encapsulates a whole series of resonances susceptible to feed the background of a story. That’s why the works of fiction trying to recreate the last hours of a leader, or the exhibition of his corpse, are always quite interesting. For instance, the pulse of Pablo Larraín doubts between shyness and sensationalism when it came to showing, Post mortem, Salvador Allende’s autopsy; a moment characterised by a chilly mood in which the forensics undertake their tasks in front of the members of the new Chilean government and coup d’état. And in ¡Buen viaje, excelencia!, a failed film in many aspects, Albert Boadella and theatre company Els Joglars wanted to imagine the last days of Franco with a frame of rottenness that translated itself into the physical and mental decadence of the caudillo, and which ended with a bloody harsh remark that sorted with some grotesque virulence the little humour of the whole play, but which couldn’t surpass Joan Brossa’s solemn verses in Final!, a poem written right after the much parodied announcement of the death of Franco by (“Rata de la més mala delinqüència, / t’esqueia una altra mort amb violència, / la fi de tants des d’aquell juliol. / Però l’has fet de tirà espanyol, / sol i hivernat, gargall de la ciència / i amb tuf de sang i merda, Sa Excremència!”). With similar transgressive spirit, Quentin Tarantino “improved” the death of Adolf Hitler in Inglorious Bastards, having him repeatedly shot at a burning cinema erected as tomb of fascism and allowing cheap fiction to beat official history.

The last author to imagine the tragic minutia of power has been Albert Serra, who has travelled in time, helped by the memoirs of Saint-Simon, to let us witness La muerte de Luís XIV [The Death of Louis XIV], an agonic and extremely intimate decline that the director shoots without any kind of irreverence, establishing a respectful and peculiar distance with the monarch. We could almost say that he observes him with certain affection, maybe in the sought-after confusion between character and actor playing him, Jean-Pierre Léaud (another body that is more than just a body, as it contains many images and sentimental memories). Finally, as the title anticipates, death beats the king’s body and its subsequent autopsy reveals a gangrenous organism that neither absolutist power nor medicine or faith have been able to save, turning his dead flesh into the full stop of a chapter in history.

06. Post mortem: a traumatic autopsy