Gudetama is the Bartleby of the emoji. An egg yolk that is an ode to idleness and to the maxim “I would prefer not to”. Víctor Navarro Remesal introduces you to this Japanese phenomenon.

Let’s play at

by Víctor Navarro

Playsam wooden toys: playing around with Scandinavian design.

In The 40-Year-Old Virgin, Steve Carell has to sell his action toy collection in order to mature and no longer be a virgin at forty-one. In Toy Story 2, the villain is a toy collector who wants to exhibit Woody in a museum. Fourteen years later, in the short film Disney Pixar’s Toy Story of TERROR!, Pixar retrieves the idea of a baddy who speculates with selling toys in eBay. Even The LEGO Movie, whose discourse about games and creativity is a lot richer and more subdued, makes Will Ferrell an antagonist for having forgotten how to play with his LEGOs and not sharing them with his son. Now that it seems that geek culture (careful, the culture, not geeks themselves) rules the world, we would expect the adult toy collector to be considered as someone with an enviable cultural capital, but it isn’t like that: Hollywood still presents him (it’s always a man) as an immature, obsessive and disconnected from the world type of guy, a solipsist who, on top of that, deprives the child of what belongs to him in his own natural right and commits the biggest crime possible: not taking toys out of their boxes.

Toys, as objects, don’t make things any easier. They have become an unavoidable and cynical part of merchandising, one of the faces of the most absurd and a-critical form of consumerism, and are a first-rate reason to laugh at this. It’s cool to make fun of Nicholas Cage’s action figure in Ghost Rider, of Bob Hoskins’ one in that horrible Super Mario Bros film or of those Chinese imitations that don’t even come near to what they try to imitate (my favourites: a Superman re-christened as Specialman or a human ninja with a ninja turtle head and an undecipherable name: Amicable Herculean). They’re pop’s most compulsive side: each character appearing on Star Wars, even if it’s in a single frame, has its toy, and that isn’t even the worst case of exploitation: did you know there was an action figure of the piece of meat that Stallone beats up in Rocky? And of the fog in John Carpenter’s The Fog?

Leaving aside the truth in caricatures, I’m afraid that the mockery of those archetypes (the obsessed collector and the money-wasting figures) has created a blind spot. Neither academia nor cultural criticism have treated toys as they deserve, and with that lack of attention the conversation is monopolised by selling numbers, psychological studies performed on children or the emotional discourses of adult fans. We have lost our train several times, like when or Weinstein cancelled the manufacturing of Django Unchained toys. We did better when toy companies ignored Rey from The Force Awakens, or the Black Widow, maybe because the gender question has gained an important place in our debates. But in general, we don’t pay any attention to toys, despite the conversation being there already: Who’s the target of those action figures? Can you collect them even if you’re not going to play with them? What makes them different from any other decorating and collector’s objects? Are they really that trivial? What do toys suppose as a cultural constant?

Luckily, some academics and critics have devoted hours and pages to answering these questions and from all of them we can extract some keys (apart from the most immediate one, playing) to come up with something like a toy textual analysis manual, which could include the following points:

Web site ChrisMcKenzie.com is a mysterious and addictive digital plaything.

Sylvanian families had love coded in their design.

Fiction

First question to study this thing we play with: what does it represent? A toy almost always refers to a second thing (a gun, a kitchen, Darth Vader) without having its shape or its function. That is, it’s a fake. Walter Benjamin, enthusiastic collector who wrote many texts about toys, referred to that representation as ‘imaginative masks.’ He thinks of those masks as fictional worlds: an Indian bow as containing all westerns in itself, Rocky‘s piece of meat not referring to a meat shop but to a whole film.

Marc Steinberg is a manga and anime expert who has written about Japanese toys and their relationship with the creation of characters (it isn’t a small matter: Japan is a country obsessed with adorable creatures, to the point that they have ninety-two yuru-kyara, or municipal mascots). Reading him it’s clear that toys are able to sustain their own fictional universe without having an origin in books, films or videogames: think of Hello Kitty or Rilakkuma. Cases such as the Transformers are now the norm: first the character, and then the franchise.

Of all these universes that have come out of toys, the one I find the most amazing is He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, built with bits and pieces from Star Wars, Conan the Barbarian and superhero comic books, with the only and honest goal of making kids mad about it. Without it being subjected to any kind of mythology or even a meaning, Eternia became the perfect space to synthesize the pop culture of the time. It’s camp, and even kitsch, but we have to admit that its personality is captivating. Not long ago, Dark Horse published two deluxe volumes, The Art of He-Man (including designs and illustrations) and He-Man Minicomic Collection (more than two-hundred pages including all the comic books that came with the action figures), so well edited that they seem Taschen books. They’re a commercial concession to nostalgia, yes, but also a way of capturing with care that anarchical and energetic universe: a world created only and exclusively for playing.

Object

After analysing what toys stand for, we should look at how they’re made. Benjamin paid close attention to their size (toys are the cousins of miniatures) and manufacturing conditions. It might seem obvious, but this perspective helps us to understand things such as the boom of tinplate toys in Japan after World War II: disarmed and occupied by the US (a country that had stopped tin toy manufacturing to devote metals to the war effort), Japan directed a great deal of its industrial energy to this field, with products thought for the American consumer, like Nikko Toys’ Newsboy. And from there to technology, videogames and the government’s strategy: that is, being cool as an economic and political strategy.

Manufacturing also leads us to thinking about authorship (or the lack of it), and from there we move on to toy-art, or designer toys. Maybe the best known among these are Takashi Murakami’s, with statues that he afterwards turns into commercial toys and vice-versa, and Tatsuhiko Akashi’s, whose bearbricks are almost the movement’s icons. Though cool, these urban vinyls seem somewhat tricky, since they grant value to toys by transferring to them the cache of institutional art. A bit more interesting are the fighting robots that Tomohiro Yasui makes with paper, because the contrast between the figure and the material it’s made of, and for uniting technology and origami. And at the other end of mixing authorship and materials, there’s the democratization that 3D printers and DIY toys might bring.

The art of He-Man was an even more pulp Frazetta, an invitation to imagine, play… and buy.

Akashi’s bearbricks.

Skeletor visits Mo-Larr, Eternia’s dentist, in a Robot Chicken sketch.

Before The LEGO Movie, Lord and Miller already played around with toy conventions in sketches such as this one.

Love

After representation and manufacturing, the loving thing: for Benjamin, toys are also defined by love, and it’s love what gives an ‘aura’ (what we feel before an unrepeatable work) to mass-produced objects, what makes a toy different from all its equals. That’s why toy-art ends up being redundant.

Love, at times a-critical and unconditional, is one of the main characteristics of the fan. We love our toy, but I’d also add that we love the character or franchise it represents (something not too strange in this our brand love and Apple sect times), or even the idealised memory of the past it triggers. Is love the reason why collectors don’t play? Does nostalgia justify our missing such horrible creatures as Trolls or Tacky Stretchoid Warriors, a mixture between the Knights of the Zodiac and the sticky hand? Is leaving the box intact like taking care of a time capsule?

Be it as it may, we always love our toys, and this makes talking about eroticism (here we go!) unavoidable: there’s German Bild Lilli, the origin of Barbie, a figure for adults taken out of adult erotic comic strips. And yes, there’s also a paraphilia: agalmatophilia, both the sexual attraction towards toys and the fantasy of becoming them. When you think of it, this love could be the reverse and needed condition for the fear of puppets and dolls (pupaphobia, automatonophobia) I talked about it in a past article: is it not precisely because we see in them something we love and desire that we fear they might turn against us? Do we feel uneasy before the realism of ? Wouldn’t it have been better for Aphrodite to leave Galatea alone?

Let’s be honest: there’s something magnetic about sad toys.

Shakespeare, Freud and Jane Austen have their own action figures. Has anyone actually played with them?

Transgression

Finally, there’s no toy that doesn’t invite us to transgress, since both games and love imply breaking some norms, logic and meanings and transforming things: now this shoebox is a treasure chest, now this figure is alive and is my best friend. Game academic Miguel Sicart (who devotes a whole chapter of his book Play Matters! to toys) insists on it and also talks about those mobile apps, simpler and more anarchic than a videogame, that turn machines into playful objects. Sicart gives Noby Noby Boy, by genius Keita Takashi, as an example, a bunch of silly applications for iPhone with no goal or end whatsoever. Those are the best transgressions: turning something useful into something non-productive… and improving it!

Toys seem to carry with them, in their form and fiction, their own instructions for use (and in this sense, I’m fascinated by the concept of toys-to-life, such as Amiibo, physical objects with videogame codes), but at the end of the day, those who play have the last word on the matter: what if that bow is really a laser gun? And if Optimus Prime has self-assurance problems or Skeletor can’t pay the rent?

That’s what Robot Chicken does: a sketch show animating with stop motion techniques real toys such as the Masters of the Universe, G.I. Joe or Strawberry Shortcake dolls to subvert them and introduce them in the world of adult misery. How is Eternia’s gym? What would happen if cartoon villains had to share a car? Robot Chicken (created by the magazine ToyFare team, who already experimented with photonovels and set-ups) is the definite pop mischief, but it’s not against toys, it only exaggerates their essence: when the meaning the toy proposes meets the meaning we want to give it, we’ll always end up winning. As a final demonstration of this, look at what a Twitter user achieved with a in which her Ghostbusters dolls came to life (you see!?) and abused, as cruel Nazi feminists, all of her male toys, making Kylo Ren cry and stealing the Batmobile from Batman. With such a degree of imagination, how could the adult collector ever be the baddy in the film?

Only Star Wars could turn an extra with an ice-cream maker into an action figure.

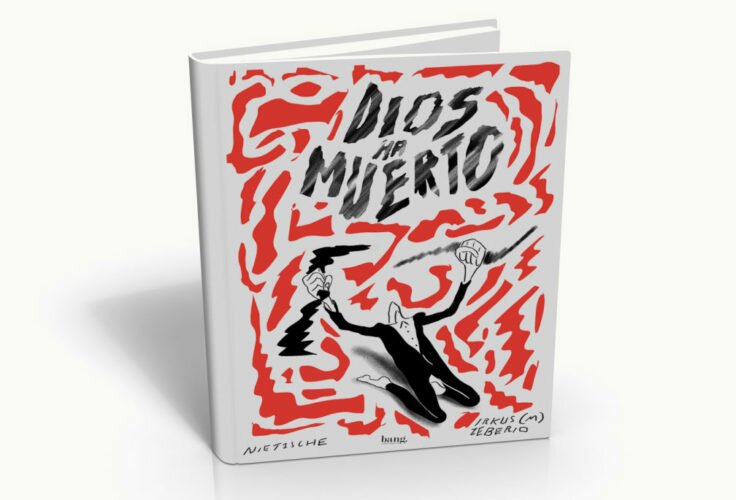

Is it a tangle of grey hair? No! Carpenterian cult as action figures’ last frontier.