News

Interview

with Eddie Izzard.

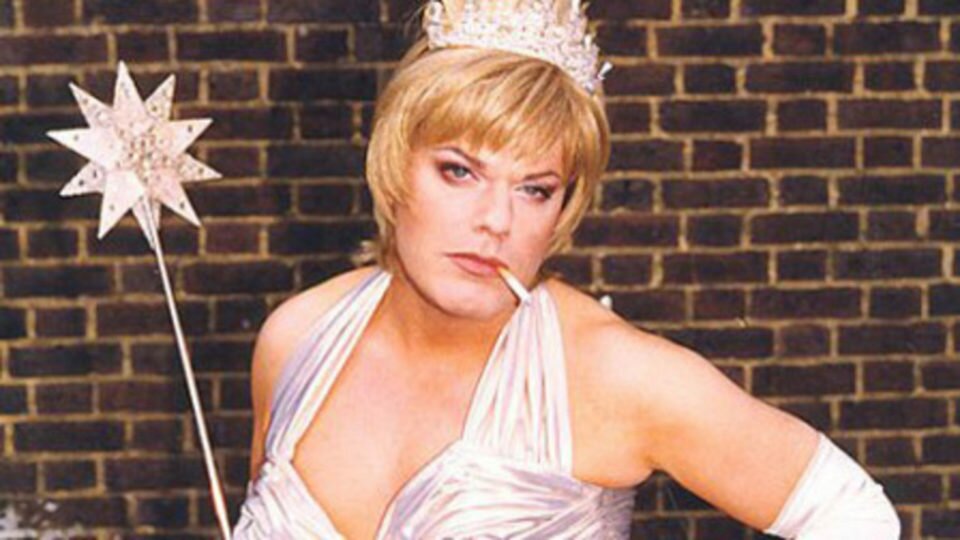

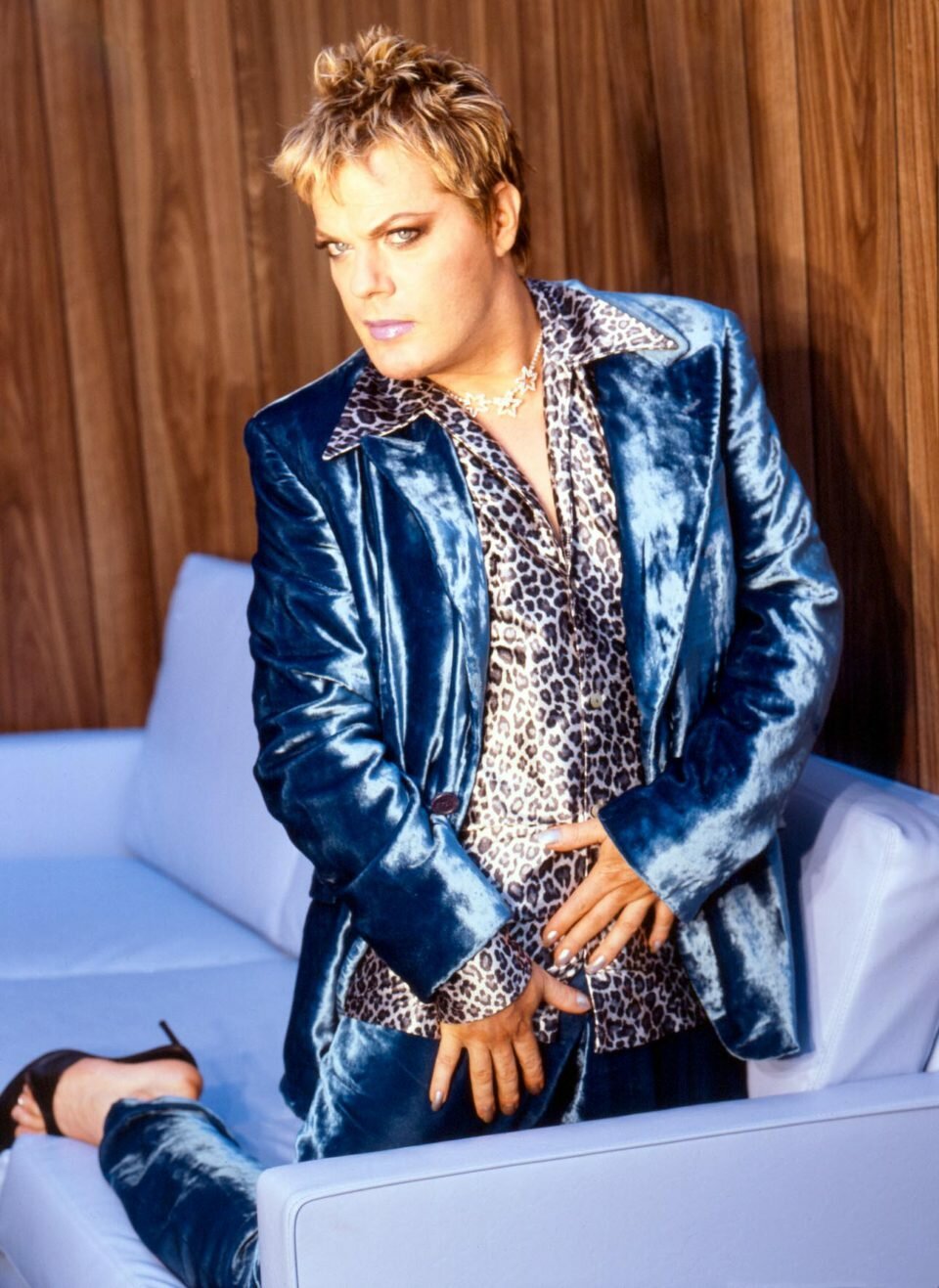

Eddie Izzard (Colony of Aden, Yemen, 1962) is an English stand-up comedian and actor who defines himself as transgender: he cross-dresses -the bottom part, mostly, like an upside-down mermaid- but he’s heterosexual. “I’m a lesbian trapped in a man’s body,” as he himself describes it. Izzard has been making us piss ourselves laughing since the eighties with extended monologues such as Glorious, Dress to Kill and Sexie, among others. He’s also appeared back there, with an unaffected rictus or clowning around, in mainstream films such as Valkyrie, The Avengers (the sixties camp series ones, not the superheroes) and the remake of the Ealing classic Whisky a Go-Go, to be premiered yet. Izzard is no short of work, and any time he has left he devotes to suicidal mad enterprises such as running forty-three marathons in fifty-one days (with no previous experience, just like that) for the charity organization Sport Relief.

Even though he’s a celebrity in his country, Izzard has been touring Europe for two years with his latest stand-up show, Force Majeure, both in big theatres and more modest clubs. Up to there, something plausible, but normal. The extraordinary thing is that stubborn Izzard has decided to perform parts of the show in the language of the country he finds himself in. Parts that keep on growing as the tour advances.

It was unforgettable to have Izzard ten inches from my nose at Teatre Llantiol a couple of months ago, delivering some of the greatest hits of Force Majeure (Caesar salad and Marc Anthony chicken, Darth Vader at a self-service…), and was even more so -I had to see it to believe it- an encore in Spanish. It wasn’t just a couple of “cojones” and three “mierda tío,” but twenty minutes of Eddie Izzard in a non-embarrassing (although somewhat stuttering) Spanish. I’m not sure whether something like this is highly recommended; but it can’t be denied that the thing takes guts. Next month he’ll be back in Spain to offer a dozen more shows in which he promises a full hour of Spanish monologues.

The almost unedited conversation you’re about to read took place in Barcelona, at a terrace of plaza Bonsuccés, during a mild Sunday morning of the beginning of November. With an Izzard clad in full Izzardian attire: pink beret with Union Jack and EU pins, perfecto leather jacket, high-heels, femme fatale nails and red lips. Like a cross between Captain Sensible and Ru Paul. It’s obvious that the expression “traffic-stopping” was coined for his sake.

You had an unconventional childhood: you grew up at the Colony of Aden, in Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and then moved to a tiny Welsh village. Do you think that wandering past made you the person you are and had some kind of influence in your comedy?

It’s an interesting question [he thinks about it for a few seconds]. I think the unconventional nature of my childhood influenced me and my brother (who’s two years older than me, a language teacher and who comes with me in this tour), of course. You can be born very far away and somehow ignore that fact. I guess it depends on how you’re genetically structured and on what you inherited from your parents, but some people are born at the other end of the world and hate everything around them, becomes a racist and hates his adopted culture. We weren’t like that. We loved living in an Arabic country. I thought it very exotic and it still appears on my passport: Aden. “City of origin,” not even “country” (because it was a colony). The last thing I went back there in 2008 I showed it to everybody [he smiles]. My mother was an actress, and acting comes from her, she loved singing and sketches, and performed pantomimes in Aden, and after that she sang at the Albert Hall. She wasn’t famous, and in the photographs you can see her fighting to be recognized among all those men. And my father had this great sense of humour that my brother and I inherited. My brother shares this inheritance with me: sense of humour, a taste for languages and an international point of view. We’re half equal and half different, at 50%. Unlike him, I tend to grab whatever comes my way and I’m not much bothered by attention. Or maybe I’m desperate for that attention? Maybe it’s because my mother died when I was a child. Although she was also his mother, of course. But it affected us in different ways, that’s quite clear. I started acting because my mother died. That’s interesting: right before she died, when I was six, she made a crow disguise for me, for a school play.

It’s quite a Gothic choice.

[He smiles] It was a friendly crow, not a Gothic one. My mum sensed I was going to like the stage, so she made me a top hat, a beak… People laughed quite a lot, even though I wasn’t trying to be funny. I wasn’t trying to be anything because I didn’t really know what was expected of me. I watched my mother perform in January 1970. And I loved it. I guess that was the turning point.

Did you like standing out when you were a child? Because up to a certain age there’s that will of not standing out too much, of being like the rest… Fitting in. And being weird or different can make things difficult.

I think I did, I loved standing out. After that, “my first play,” I enrolled in any other school production. I didn’t like studying that much. I loved football, I lived for football, I was a total tomboy. A tomboy boy. I lost the love of my mother when I was six, my father was away two thirds of the year (I attended a boarding school). I guess I needed other people’s affections. I didn’t mind standing out, but I hadn’t realized the use of performing in a school context. I loved comedy, but I wasn’t conscious that I could do it. I started playing around with comedy at sixteen, and with the same teacher as my brother. He was a Chemistry teacher and left blanks for pupils to fill-in. “We have sodium, and we place it in _ _ _ _ _”. “In his ear, sir”, I said [he smiles]. He spoke very slowly and you could insert funny things in between what he said. And so girls started noticing me [he winks]. Because I made the classroom laugh. Being the classroom destroyer made me feel quite well. I had always wanted to perform, and it was then when the schism appeared in my brain: comedy or drama? I loved both, but I wasn’t good at drama, whereas I was good at comedy. I forgot about drama and started doing Python-style comedy. After a long time I decided to try and accept some dramatic roles. What I’ve done (spending so many years doing comedies and now starting with dramas) is quite weird, but no that much. Look at Hugh Laurie: he did absolutely absurd comedies. In Black Adder, when he was The Prince Regent, he was the king of clowns. And years later he did House, and I think that’s what he had always wanted to do, and now he almost never accepts any more comedy roles. I see myself that way, but for the moment I’m doing both things at once. What is, of course, very shocking for the people around me: studio owners, journalists, agents, managers… But I think it’s beautiful.

For what I see, you made very important decisions (being trans at four, becoming an actor at seven) very early in life. In that sense, you were really precocious. I mean, the most categorical affirmation my son has ever uttered is that he doesn’t like carrots.

[He laughs]. OK, I need to put those affirmations in context. In hindsight, I think that at four or five I started having trans feelings that I was obviously unable to articulate. I sensed I had a different sexuality, but I told no one because they would have punched me in the face. And in any case, as I said, I was quite the tomboy: I wanted to run, kick football balls and later I planned to join the army’s Special Forces. So I knew there was something going on, but I couldn’t name it and of course I didn’t talk about this to a single soul. I didn’t stand up in the middle of the class and said: “I define myself as transgender, even though…” [he smiles]. I wasn’t that mature at five. And when it comes to the acting thing, again I see this in hindsight. I remember a theatre play about a guy and his cat in which I managed to enrol, and the feeling that it was fun, but not much more. As years went by I kept on performing in plays, and the idea that it was meant for me crystallized in my mind. At sixteen, in particular, when I started doing job interviews, my father and stepmother insisted I should study a proper degree and find a proper job and I decided to pretend I listened and I was going to become an accountant or whatever. But it was only a façade. At sixteen I already knew I would have to accept studying a university degree to make them happy, but what I really wanted to do, and was going to do, was to become an actor. In my mind, this was articulated as follows: “I will become an actor, and fuck anything else.” I stand whatever it takes, and then I will follow my ambition. But I didn’t even stand university for a year, of course. Fuck it. I realized if I got an accountant title, my stepmother would use it against me.

Would you say that humour was for you a kind of weapon of self-defense? For many nerds that are quite useless in sports or completely devoid of testosterone, becoming the court’s joker has always been their salvation.

I see [he nods]. It wasn’t exactly my case, because even though I didn’t like fighting, I did like arguing and I stood for myself, I never let anyone pull my leg. I was too much of a problem for bullies because I always answered back, and in the end (out of sheer exhaustion) they let me be. I always tried to project that non-victim halo for them to know that if they decided to come for me, there would be chaos. In time they decided to look for someone easier to bully. At sixteen, the problem was girls. I was transgender, who hadn’t come out of the closet, and I liked girls, and that was very complicated. In my school, girls weren’t admitted between thirteen and fifteen, and then all of a sudden at sixteen they were there again, and there were twenty girls for a hundred guys. And at the time I still didn’t know how to joke, I hadn’t made that click. I loved listening to comedies and seeing them on TV, but for me they had nothing to do with what I did. One thing didn’t correlate with the other. I remember I was walking down the street and someone in front of a cinema shouted at me “ASSHOLE!” and I didn’t know what to reply. After that I thought it would have been wonderful to have a devastating sentence at hand to answer to that. Maybe that’s where the question of my inner desire resides. Because from then onwards I always know what to say to an idiot. Street theatre teaches you that, among other things. So when I was preparing my Science A-levels…

That’s also quite nerdy.

Yes. Totally. But I was a sporty nerd, as I said. Still, at the posh boarding schools I was sent after my mother died, football was banned because it was too “working class,” and they made you play rugby. And I didn’t like rugby, so that killed my sporty side. At the same time, it also seemed to finish with my opportunity to be the best at something, because I was top of the class at sports, so I had to look for something else to make me shine. And then girls came back, and they were only interested in handsome rugby players, of course. I was different, I looked really weird. And so comedy became a providential tool. I even wrote a play at sixteen. A shitty play, unfortunately. Everything copied from elsewhere…

Well, that’s the way, right? First copying the masters and then finding your own voice and stop copying.

Exactly, my friend. Isn’t there a sentence by Picasso that says something like that? “Good artists copy, great artists steal” [also attributed to T. S. Eliot]. If you’re one of the greats you can start stealing from others. I usually use other people’s sentences, but I say who they are and when they said them. Because they’re amazing quotes. But you need to mention the source, of course.

You’ve affirmed more than once that the death of your mother made you a stubborn guy, ready to do anything.

I’m not sure. The death of my mother left me empty and completely desperate, and at the same time that awoke my hunger to perform, as a means to replace her. I don’t know if that’s what made me determined. I think that was already in me.

You defined yourself once as a “tenacious bastard.”

I am. I’m getting involved in politics now and tenacity is proving quite useful. I came out of my very own closet thirty-one years ago and I feel perfectly ready to go out there, travel to different places, stand for things. I’m sure Barcelona is very modern and progressive, but people look at me funny here [he smiles]. The same happens in London, but here I’m not so tuned to the local spirit and I can’t read their looks yet. But I’m the kind of person who is going to join the arguments that will take place in the future. If a bloody dickhead as Trump is going to win, and the Brexit hatred is going to take place, I feel I need to counteract those negative forces.

Let’s go back to Brexit. I guess what I wanted to ask when I mentioned your determination was that it seems you always get what you want. I wonder whether you have ever failed at something. And I mean an epic fail.

Oh yes. I think I’ve failed quite a lot. I started becoming popular as a comedian at thirty, and I left university at nineteen. That’s eleven years of failure, depending on how you look at it. I did twelve shows at the end of a festival, and the first were a complete fiasco. That’s how you define a failure: like something that doesn’t work. The kind of club where I performed for the first time told me not long ago that my show back then was “a piece of shit.” He could recall it perfectly.

That’s not exactly the nicest thing you can say to someone.

No [he laughs]. But after failure I’m relentlessly positive. When I created those first shows, what I thought was that it was incredible for someone like me to have written and performed a whole show. No one in my university had done anything like that. That seemed to me quite brave at nineteen (I’d left my degree merely a year earlier), even if the shows by themselves weren’t great creative achievements. In summary: I’ve had my deal of failure. Four years ago I had to stop my challenge of running twenty-seven marathons on twenty-seven days [for Sport Relief, commemorating the twenty-seven years of imprisonment of Nelson Mandela] after only four days. You see, four marathons in four days is not that bad! Some people would consider that a success. But that wasn’t my goal. I failed. But the trick is how you take things. I’m always positive: I took it as training for the following challenge, which I managed to complete.

Success should come late in life. Kurt Vonnegut used to say that no writer should write before he’s thirty-three or so because he hasn’t lived enough.

I think that’s true. That happens a lot in the world of pop music, when someone very young becomes very successful, and they start to think: “if I’ve made it here so early must be because I’m really brilliant. I must be THE BUSINESS.” And then success goes to his head and ego problems appear, and the incapacity to deal with failure… The thing is that I have refined this along the line, for many years, and if I ever become really good will be because I have analysed it and mixed it with my instinct and mixed it all up and, BOUM, it works. What I’m doing it in this series of shows is giving them in English, but with a ten minute encore in Spanish that will be increased as the tour progresses. This provokes an unusual reaction, because when I’m back onstage the first thing I say is: “Entonces, me he dado cuenta de que todos los animales salvajes están en forma…” And I say this very quickly, without warning anyone. And there’s a moment of general confusion [he smiles]. Then I go on, making lots of mistakes, no doubt, but I like it. Because it’s fun. Wait a minute: what was your question again?

Whether it’s important to become successful late in life.

I think it is, although when I was young I didn’t want to become successful later in life. I wanted it NOW. At twenty-five, tops. And when I saw I was twenty-four and a half and things weren’t working I thought: “shit!” What happened is that my material wasn’t good enough. I had the rest: presentation, image, promotion… but jokes weren’t up to scratch. So I let go of anything superfluous. I stopped worrying about promoting the show and started refining the jokes time and time again. And that’s what made the difference. Remember that beautiful Kevin Costner film, Field of dreams? “If you build it, they will come.” That’s the motto. If I refine the jokes, they will come. So I worked non-stop and started performing almost with no promotion and I saw how more and more agents asked my number after each show. I remember one time I performed in Edinburgh, on the street, and I was setting up my stage when a guy looked at me and started running in the opposite direction [he smiles]. I thought: “this doesn’t look very promising”. But after a while the guy came back. With his whole family! Because he’d seen me before, and that’s when I knew. I used to do the same when I was a spectator of the comedians I really loved. Then I saw I had “it”. The lightbulb went on. Because it’s something you don’t control, you don’t know you have it until you see people’s reactions.

Shit-swallowing times are very important for any artist. The Beatles wouldn’t be the Beatles without the Hamburg years, playing hours and hours for whores and drunken sailors.

[Convinced] I totally agree with the Hamburg thing. Yes. My London years are my Hamburg. Everybody should be made to leave his or her comfort zone, made to feel uneasy. Spanish stand-ups should go to London. Because I’m doing the opposite and I’m ready to swap seats [he laughs]. Not only for creative reasons, which are fundamental, but for all the shit going on and the walls they’re trying to build, and their “hate this one, hate that one”… In politics, I’m a “moderate radical.” That’s my thing. I do radical things with a moderate message. That’s why I would like to push Spanish or Catalan artists…

Us Catalans are obsessed by language, I don’t know if you’re aware of it. If you say something in Catalan at the theatre you’ll probably be on TV.

I totally understand. What should I say?

If you say “independence” you might get your own stature here.

Mmm, no, then it will seem as if I’m taking sides. I need something less divisive. Like a swearword. Swearwords always work.

Bill Hicks, now you mention it, used swearwords and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, while one of the shticks of your shows is history: prehistory, biblical history, Victorian age, World War II…

I don’t really like the word “shtick”. Let’s call them my “topics.” I cover all periods: Middle Age kings, Stonehenge, the day before fire was discovered… It’s a human thing. I try to be a student of humanity. There isn’t a single period I’m not interested in. The key is to distil them. No matter whether you’re a journalist or a comedian, the main thing is to look for the core in anything. Analysing. Distilling. And if I distil humanity I can extract repetitions. The failures we repeat time and time again. The charismatic bastard who appears in every age, appeals to people’s lowest instincts, and shows them something to hate and everybody follows him. And that’s a disaster, and it just happened again, both in my country and in the US. But other people try to mobilise people to do good things. Like Bob Geldof. Let’s move together in the same direction. I’m proud of my country but I want to lend a hand to other countries, let’s learn from each other in an equal-to-equal state, without anyone being more than anyone else. I don’t want to be the #1 country. Fuck #1! Humanity should be #1 [he cheers imitating a crowd] “Human beings, number one!” Because the other thing doesn’t work. I love that you mentioned Bill Hicks. I saw him live once and I admired him, but it wasn’t my thing. He went to the dark side, I don’t. When I recently campaigned for remain what I told young people was that we should move forward, not backwards, to the future.

Do you think we’re going backwards? I’m talking about a World War II scenario. That seems to me a bit catastrophic.

I think so, I think we’re going backwards. Just think of what a loony like Trump could do, his fingers pushing the buttons. There should be a force opposing that. We called World War I “the war that would put an end to all wars.” And then we had another. Another guy appear to sow discord when things started to go better. Unemployment was reduced, industries progressed, but then there was the crack of 1929 and a guy took advantage of the catastrophe. Only an idiot could look back and not realise that something like that could happen again. We must learn from it.

History is really good for humour. Because the history of humanity is just grotesque. Mark Twain said that “tragedy + time = humour”.

Us humans do many stupid things, that’s undeniable. In the show I talk about Bad King John, who had no idea where France was and that’s why he lost his land there, and of his brother Richard the Lionheart, whom we consider the greatest of all English kings, but spoke only French, and who was fooled because I got to England saying, “What? ¿Pardon? Je ne parle…” This isn’t what happened, but the comic version. People learn things in my shows. I also talk about how the Caesar wouldn’t be very happy to know his name is basically used nowadays only to describe a chicken salad. Unless his minister of war was a chicken, which is what I imagine at the show. This isn’t true. But it could well be [he laughs]. I impose my analysis and humour over real political scenarios. When the chicken tells Caesar how to lead the battle of Alesia, what I describe is the real battle of Alesia. What isn’t real is the fact that Marc Anthony was a chicken.

Of course. But leaving Marc Anthony the chicken aside, the rest gives the impression of having been studied in depth.

It was. Dates are all correct. Also the changes in the English language and the influence of French. For three hundred and thirty-nine years (between 1066 and 1399) the language of the dominant classes in England was French. What I do is to imagine two Saxon waiters that get all mixed up when writing down their orders and make the transcendental decision of dropping gender with names: masculine, feminine, neuter or “just a fucking spoon.” Their action freed English in its way to world domination.

Some things shouldn’t be funny, but they are, and quite so. Like the Nazis, probably the scariest ideology of all and at the same time the most laughable that ever existed.

It’s true. Everything can be funny. If you say a Nazi has killed someone, that isn’t funny, obviously- But Nazis were very stupid. Behind their thinking lied an essential stupidity. Like the idea that if we cross Nazi families we will get a better race. No: that will be endogamy and thanks to the British Royal Family and to dog breeding we know what comes out of that: idiots. And besides, the Nazi high ranks didn’t look exactly Aryan.

Well, except Heydrich. He was tall, blond and had blue eyes. But, unfortunately for him, he was also half-Jewish.

That’s true. I was forgetting Heydrich. Was he really half-Jewish? It seems Hitler was a sixteenth per cent Jewish. The thing is that hatred towards Jews was something as stupid as hating Methodists, or Austrians. And was very bad for the country. Should Hitler have accepted them he would have kept all those scientists and intellectuals: Germany would have had the hydrogen bomb before anyone. And wouldn’t have had to kill all those people. Who would have fought on their side on top of that, because they were German after all. You just can’t be more stupid than that. But there was something in what Hitler preached that eased the lower instincts we mentioned earlier: hate the neighbour. The greatest disgrace for the Nazis was that they were dumb and at the same time very well organized. I would love modern Germany to save the world, because they have a democracy that works, a powerful economy and because they’ve been to hell and don’t think they should ever go back there. I think the Trump thing was rejected by Germany, and that’s a hopeful thing to see.

I’m forty-five and I’ve seen Reagan and Bush father and son in the White House. Can Trump be worse than Reagan, I wonder? Is he even madder than Bush Jr., who really believed in the existence of hell?

It makes you think. Hitler had a “moderate” phase. He pretended he was a cool guy. There are pictures of him in a meeting with the first cabinet, offering a chair to someone and holding the door when coming in [he smiles]. But then some things happened and he entered a radical phase. Bush Jr. also pretended he was a good guy until September 11th, and after that we entered a new destructive phase. Brexit and Trump are two very bad news, in any case.

The Brexit thing must have caught many English people off guard. It seems nobody expected it really, not even its supporters. I bet they hadn’t even written their speeches!

Look, in 2008 we had a crisis because a few greedy guys took advantage of Reagan’s and Thatcher’s policies to fuck the rest of the world. That happened and the government decided that austerity was the way o get out of it, and the poorest were affected again, and so when voting time came, right-wing newspapers blamed Europe for unemployment. What was to blame was the crisis, not Europe. They said they were going to invest three hundred and fifty million pounds in social security, and the morning after they issued a disclaimer.

I’ve got to say that I’m surprised you still support Labour, after Blair’s deceptive policies.

You have to look at all we did, from the Olympic Games to money invested in schools, and all that was thanks to Tony Blair. We were in three wars: with Milosevic in former Yugoslavia, in Sierra Leone and then Iraq. Two of them ended up well after the British intervention, but not Iraq. What happens is that everything colours Blair’s policies with Iraq and nothing else. I think everything should be remembered. I’m with Corbyn, and Labour is stronger than ever. As I said, I’m a moderate radical. I don’t reject businesses, if the principles ruling them are ethical, and I defend the trade unions if what they demand is fair. A positive thought: we’re not in 1939. We’re not in 1940 France. That must have felt quite hopeless. But in the same way in which a single person can destabilize the scales towards negative thinking, I think that a single person can do the opposite and redirect people towards positive goals. I’m part of the Labour congress, I got seventy thousand votes, and I will try again in two years. I want everybody to be OK. As you mentioned earlier, I’m a “tenacious bastard”: I want to go on with this show, travel to more countries, learning more languages… I’m competitive, although I hope in a healthy way.

What you do with other languages is amazing, taking into account how gloriously bad English-speaking people are when it comes to speaking any other language in the world.

We’re lazy. Very lazy. While the rest of the world learns more and more English. English is the second language of half of the planet, a way to connect. And that’s beautiful. Because we never invaded with this language.

Well, except in India. And North-America. And Africa. And part of China.

Well, yes, yes [he smiles]. We had en empire, but we lost it all very dramatically. It was both Hollywood and rock ‘n’ roll what made English conquer the world. In an non-imperialist, non-abusive way, as far as I see it. We left it there for anyone to use. For people to understand each other. I want to believe that people will end up understanding each other. That’s why I do shows in Spanish.

There’s an elementary truth, and that is that most people just want to be left alone, and to feel safe, and have a roof over their heads and food and love. There’s only two or three nihilists out there. But those three are really the worst sons of a bitch.

Of course. I resort to that, precisely. To achieve a whole world in which we have the chance of leading a good life. Seven thousand millions of people. And we need to manage it in this century, it can’t wait no longer. We either do it or we’ll all die. Dynamite was invented in 1860, and the H-bomb in 1950. Within ninety years of each other only. What’s next?

I don’t know, but I sometimes think that us humans only learn through trauma. The New Deal and the welfare state were a direct consequence of the sixty million people dead during WWII. I’m not sure you can convince people of anything just by talking.

I think you can, you must! The people that say that can’t happen again is wrong. The Great War, as we used to call it, was meant to be the last, and in less than nineteen years there was a worse one.

The Treaty of Versailles wasn’t of great help, one might say.

Wait a minute, everybody blames the Treaty of Versailles, but no one remembers the treaty that Germany signed with Russia in 1917 [he means the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, from 1918]. Then, Germany was quite happy to humiliate Russia and to take a great portion of its territory and money. So the thing about the “humiliation” that Germany suffered should be considered with some caution. I don’t mean it was optimal, and policies such as the Marshall Plan were way more adequate, but saying that Versailles was abusive is bullshit.

Do you feel optimistic, in general?

You know the thing about the glass half empty or half full? Mine is full up to two thirds. Thirty-one years ago I came out of the closet and now I’m here. I have great trust for the good things to come, and in the centre of that confidence is the 1985 day I decided to get out of the closet. Because it was really tough. I could have spent years asking everybody what that “cousin” of mine should do, the one who was a transvestite but liked women, and one hundred per cent of them would have told me “stay well inside your closet.”

Now I’m curious: how did you get out of the closet? Onstage?

No. You have to realise that this [he points at himself] is my real life. I don’t dress up for the stage. I go about like this. I only incorporated this to my stage act six years after coming out of the closet, and because I thought it was logical. There was a help group for this kind of thing, one of the only ones in England in the eighties, and it was half a mile away from my house. Ten minutes away. So I thought: destiny has placed it here. It’s too much of a coincidence. So I we t up there, because I’m bloody stubborn, and then I came out of the closet with everyone. Except my father. With my father it took me a bit longer, because all my friends told me it was going to kill him. But it didn’t. And soon after getting out of the closet I told my first joke about it, live.

Tim O’Brien, one of my favourite authors, says that laughter doesn’t deny grief, but it’s an answer to grief. How do you see it?

[He thinks about it for a while] I believe the same thing. It’s an answer to grief. It’s self-therapy. In my first shows there were pieces about first girlfriends, and ejaculation problems, and it was very useful to reveal them in public. That gave me strength. It taught me to not give a shit, and to not give a shit about everybody knowing. I lost my virginity very late, at twenty-one, something I don’t recommend to anyone. If you’re a guy, the normal thing is to lose it at fourteen or something. But fuck it: I told it, and got rid of it, and now I hope if a guy who’s gone through the same thing sees my sketch he can think: “I’m not the only one, for fuck’s sake.” I met a protestant pastor from the US while we were shooting a film in Glasgow, and it turns out his daughter identified herself with a boy, and when they saw me they jumped over me to tell me that my story had helped them to quietly accept their daughter’s gender issues. That made me happy, because I don’t go about waving the trans flag all day. I never tried to be the spokesperson of transgender (by the way, we really do have a flag, and it’s quite sweet: pastel blue and pink). The only think I’ve done is to set an example: building a career while being transgender. And I believe in what a trans lawyer told me once: that this is a gift. And I consider it so.