Before T.Rex, Bowie or Roxy Music’s glam there were other musicians with a passion for make up and transvestism. Jaime Gonzalo rescues them.

I don’t like

By Jaime Gonzalo

In the same way that there are different calibres, there are opinions to suit every taste when it comes to the debate, not so much of whether popular music should or shouldn’t support the free possession of firearms, but whether through this it defends a culture of violence. At the end of the day, what’s real is legal, as Howard Devoto sang in Shot by Both Sides.

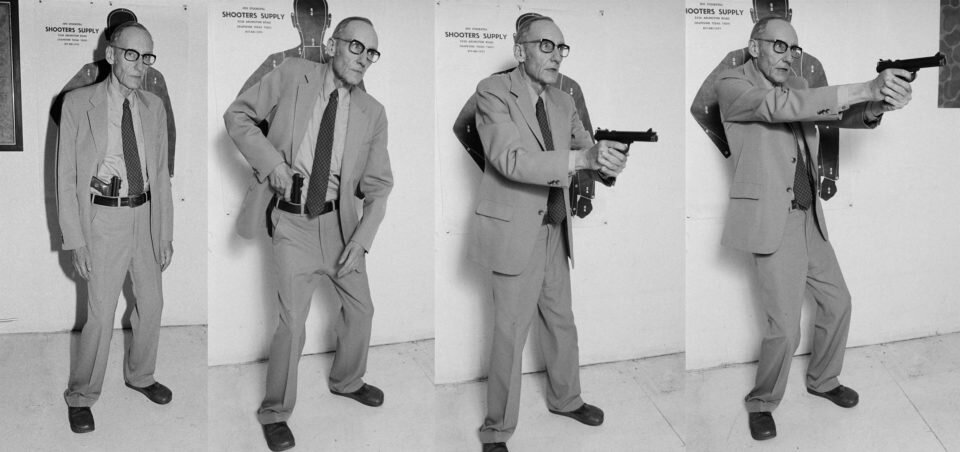

William Burroughs said so: “After a shooting spree, they always want to take the guns away from the people who didn’t do it. I sure as hell wouldn’t want to live in a society where the only people allowed guns are the police and the military.” It’s one of his most famous quotes, and it’s quite ironic that the political group Gun Owners of America used it for a on their Facebook wall.

In the same way that some need them so as not to leave people alone, Burroughs preferred using them tu buy his tranquillity. Executor of his own wife when his aim failed him whole they played William Tell, shooter since the age of eight, obsessed with them all throughout his life -he always slept with a 38 under the pillow-, Burroughs represents the opinion of millions of people, particularly in the US, where the Second Amendment guarantees “the private right of individuals to own and bear arms shall not be infringed.”

As usual, contradiction isn’t so much in the fact of possessing such arms, but in human nature. It might have vicious aspects, but armed self-defence isn’t but another created necessity, one that capitalism sponsors in favour of an industry, in this case the arms trade, and of that very human instinct by which the American collective subconscious is still living in Far West times, not willing to civilise completely. Inalienable since the American conquest, they interact with their soundtrack since the beginning of time, like drugs or sex, maybe because arms are both. And because when it comes to shooting, those balls that biology and education are always willing to make us males make use of as soon as a little spark appears have always been present. Alan Lomax said in Mister Jelly Roll that Jelly Roll Morton had enough with one of his musicians rejecting to play a note the way he had written it to extract them, the musician’s balls, leaving afterwards, on the lid of the piano, a black long barrel pistol.

Like many other jazzmen, Sidney Bechett always carried a gun. In 1928, while in Paris, he confronted another musician in a hail of bullets, it seems because of something to do with a woman; none of the two put the bullet where they had set their sight, but gravely injured three people and were condemned to a year and three months in jail. Sax player Frank Trambauer also carried a gun inside his instrument’s case. Trumpet player George Rock was never seen without his six shots Cold Frontier. Rock was right if we take into account the luck of fellow trumpet player Lee Morgan, shot dead by his wife, onstage, while he played at an East Village club in 1972.

Bang Bang Blues

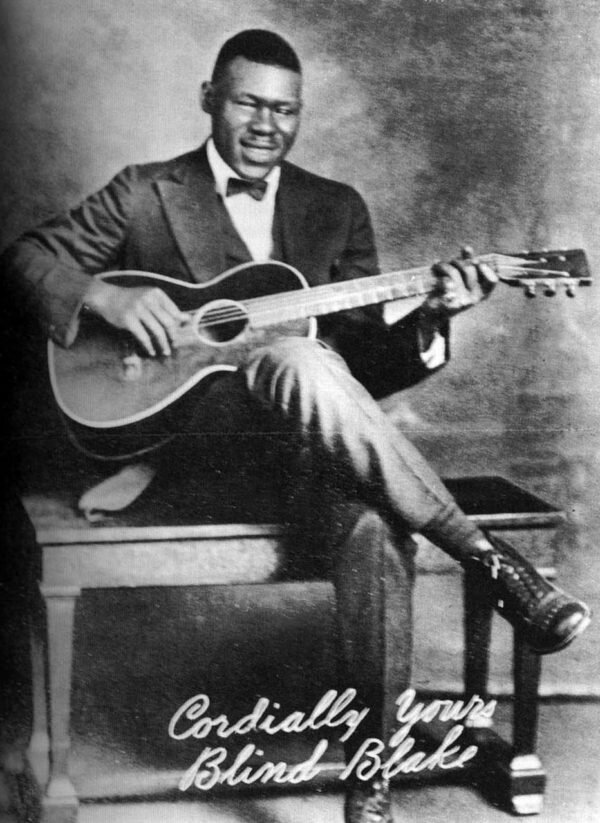

Chambers were emptied and charged at the speed of history, transversally, by all those black and white music forms that would give way to rock, blues being the most explosive one of that liaison dangereuse between arms and quick tempers. The world of twenties and thirties bluesmen breathed a climate of oppression and danger. Jealousy, debt, a few drinks, a suspicious look and… Bang! Bang! There was the Stager Lee myth, immortalised by the eponymous popular . In his case, a game of dice unchained the tragedy: “Stagger Lee went to the barroom/And he stood across the barroom door/He said, nobody move/And he pulled his forty-four/Stagger Lee, cried Billy/Oh, please don’t take my life/I’ve three little children/And a very sickly wife/Stagger Lee shot Billy/Oh, he shot that poor boy so bad/Till the bullet came through Billy/And it broke the bartender’s glass.” The smell of gunpowder permeates this genre, wrongly identified as crying and whiny… Blind Blake & Bertha Henderson’s , Skip James’s , Roosevelt Sykes’ …

Blues would build a new archetype of romantic song, granting license to kill right, left and centre in the name of betrayed love. In 22-20 Blues, Skip James invented his own calibre to express the inevitability of his gun, with which he threatened to “split (his rib) in two” should she reject going back to him. Robert Johnson also boasted about his calibre in 32-20 Blues to solve infidelity problems, but no one more obvious than Louisiana Red in : “I have a hard time missing you baby, with my pistol in your mouth/You may be thinking ’bout going north, but your brains are staying south”.

Gunfight at the Kingston Corral

A branch of US and European slavery, the African-Caribbean would be the extreme example of homicidal cultural colonialism and its reverberation through pop violence. Cult film The Harder They Come, from 1972, synthesised in one of its scenes the influence of spaghetti western in reggae not only as an aesthetic, and sometimes sonic, reference but in its sublimation of the character of the gunman. The film’s protagonist, played by Jimmy Cliff, was the alter ego of Vincent Martin, known among other aliases as Rhygin, a Jamaican amplification of Stager Lee, the original Rude Boy. A guy who at the end of the forties earned his status of legend with a vengeance, he was idealised in Jamaica at the same level as Bonnie and Clyde in the US or Mesrine in France. Two decades later, in the Kingston suburbs already packed with rural immigration, Rhygin’s “romantic” cowboy figure acquired political flavour. The so-called Dons, in a reference to mob capos, put themselves at the service of the dominating political parties, centre-right JLP or Jamaica Labour Party, and social democrat PNP, the People´s National Party. The fight for vote control in those poor and over-populated neighbourhoods derived in a war of bands, allowed by the government and armed by the CIA, the JLP, or Cuba, in the case of the PNP.

At the end of the seventies, the Dons got rid of political patrons to devote themselves exclusively to the more lucrative drug traffic. In its condition of ghetto product, reggae absorbed that eurotrash permutation of the Wild West in a kind of narcissistic gunfight at the West Kingston OK Corral. It opposed the Dons and the only ones able to undermine their influence and arrogance, reggae stars, many of whom could also express themselves through a language as universal as music: the language of guns. Save for a few exceptions, Bob Marley for instance, the list of musicians shot dead in Jamaica is longer than in any other art collective: Peter Tosh, Bogle Levy, Carlton Barrett, Charlie Ace, David Bingham, Dirtsman, Dwayne Haughton, Errol Scorcher, Free I, General Echo, Jah Lloyd, King Tubby, Major Worries, Mickey Wallace, Prince Far I, Style Scott…

The big iron

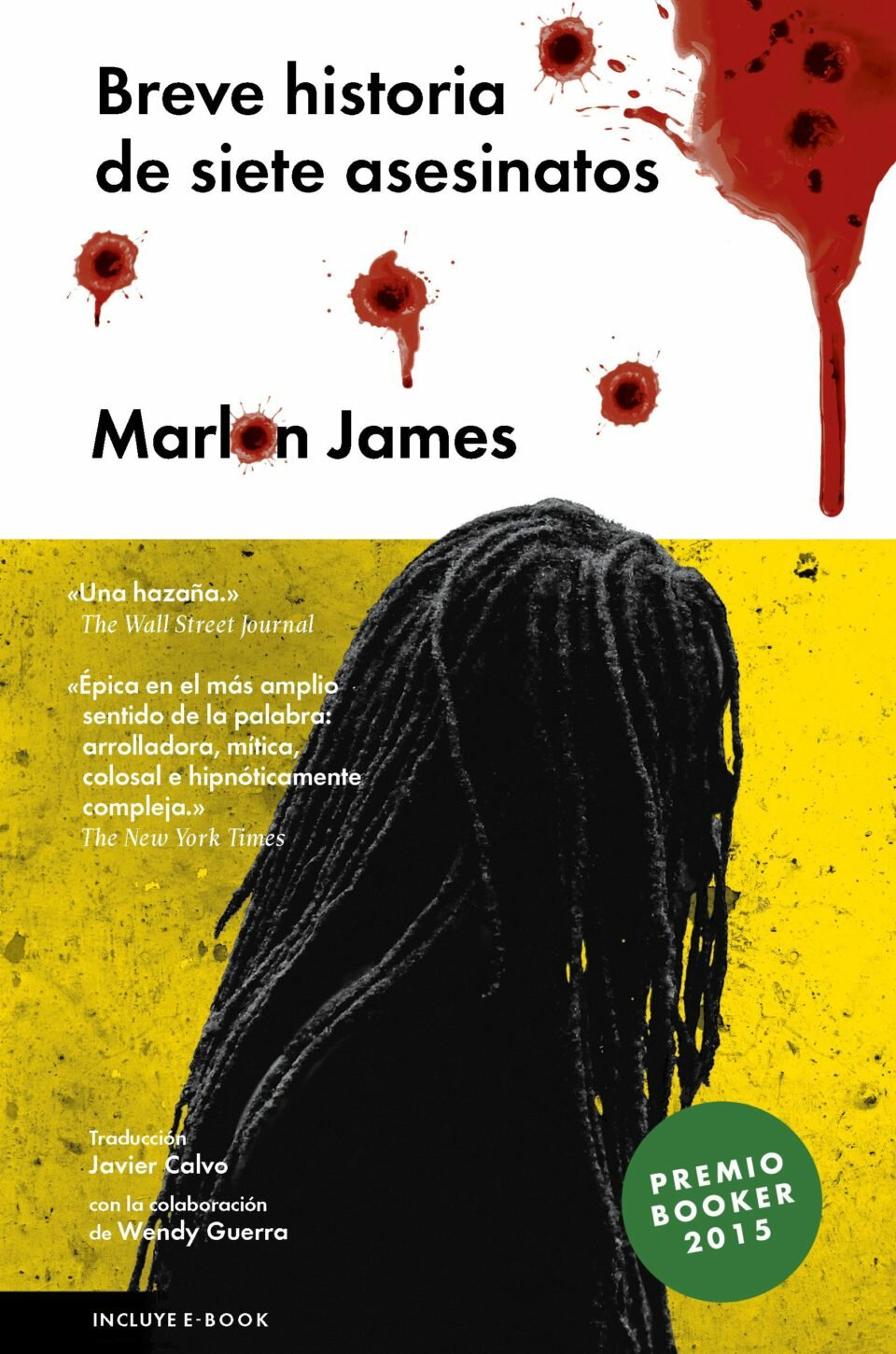

Gun songs and anti-gun songs abound in reggae and close genres, and with both we risk falling into the trap of consuming violence because around it has arisen a culture, be it pop or any other kind, industrial culture after all. Author of Brief History of Seven Killings, a novel inspired in the attack suffered by Marley, Marlon James pointed out that giving violence a cultural consistency was to simplify it way too much: “It’s politics, it’s money, it’s extortion, it’s crime, it’s an economic problem.” As happens with real westerns versus those shot in the Almeria desert, the source of that transfer of gunman imagery to the codes of popular music resides naturally in country. The Nashville industry never tires of pointing out that country doesn’t defend firearms. Its songs only celebrate guns “as a means of protection or with recreational purposes.” All throughout the present century, the links that give a different sense to the binary country & western have intensified; and its messages, even in alt country, don’t leave much room for imagination: citizens sick of urban crime decide to take action; beaten up wives ready to put an end to their problem; fathers who can no longer take the abusive behaviour of their daughters’ boyfriends… All seem firm as rocks when it comes to their right of keeping firearms. “I’m gunna tell once and listen son” said Justin Moore in , “As long as I’m alive and breathing/And I’m still breathing, You wont take my guns.”

Marty Robbins, typical seventies country star, holds the record of having published no less than three monographic albums on the subject. In fact framed within cowboy narrative, Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs and Return of the Gunfighter granted the Arizona singer his highest peak of popularity. The first is a classic, from the cover showing Robbins dressed as a cowboy, a man in black about to pull out. Among other titles, it includes : “To the town of Agua Fria rode a stranger one fine day/Hardly spoke to folks around him didn’t have too much to say/No one dared to ask his business no one dared to make a slip/or the stranger there among them had a big iron on his hip”. The stranger in question was a ranger looking for outlaw Texas Red. The duel would take place at sunset. “There was forty feet between them when they stopped to make their play/And the swiftness of the ranger is still talked about today/Texas Red had not cleared leather fore a bullet fairly ripped/And the ranger’s aim was deadly with the big iron on his hip”.

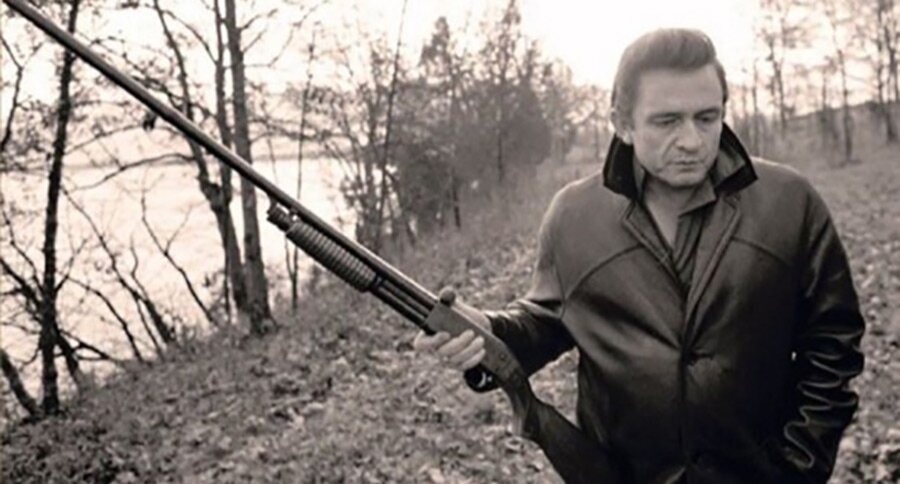

Attacking Graceland with gunfire

Johnny Cash, who would record several of Robbins’ songs, also used ammunition in both screens. In the film world he debuted with thriller , playing a manic kidnapper who tortured his victim by shooting, sexually harassing her, and, horror!, making her hear him sing. A bit more sophisticated, exposed the dilemma of two mature and bankrupted gunmen, the second one played by Kirk Douglas, who accepted challenging each other in exchange for an economic ransom and end up becoming comrades. On TV, Cash was guest star in several western series and telefilms. It’s almost redundant to bring up , the most famous of Cash’s gun songs, which includes one of the biggest psychological aberrations in gunman narrative: “When I was just a baby/My mama told me: son/Always be a good boy/Don’t ever play with guns/But I shot a man in Reno/Just to watch him die.” A similar luck had Billy Joe, an inexperienced farm boy whom in rides to town looking for fun and emotion, not listening, again, to the maternal voice of wisdom: “Don’t take your guns to town son/Leave your guns at home Bill/He laughed and kissed his mom/And said your Billy Joe’s a man/I can shoot as quick and straight as anybody can/But I wouldn’t shoot without a cause.” He finds him at a saloon, when a cowboy mocks him and alcohol does the rest.

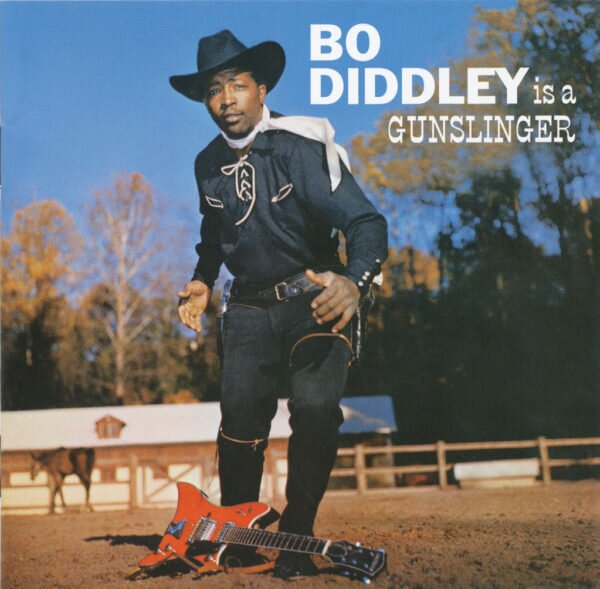

Bo Diddley, who worked as a sheriff in the seventies, when he lived in New Mexico, also succumbed to that fever in his fifth LP, Bo Diddley Is A Gunslinger, from 1960, the cover of which took inspiration in that of Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs. The only song in the album with any relation with the title was : “I’ve got a story i really want to tell/About Bo Diddley at the o-k corral/Now, Bo Diddley didn’t stand no mess/He wore a gun on his hip and a rose on his chest/Bo Diddley’s a gunslinger/When Bo Diddley come to town/The streets get empty and the sun go down.” Jerry Lee Lewis took it much more seriously, fanatic follower of the Gunsmoke series as he was. At the end of 1976 he appeared in Graceland with the intention of visiting Elvis, but the king was asleep. The following day, in the early hours, the Killer tried again, this time really drunk, with a Derringer 38 in hand and threatening to kill Mr Pelvis. Naturally, the Memphis Flash rejected seeing him, watching his actions through CCTV and asking his guards to call the police. “Lock that motherfucker up and throw the keys into the sea,” he said.

Where are you going with that gun in your hand?

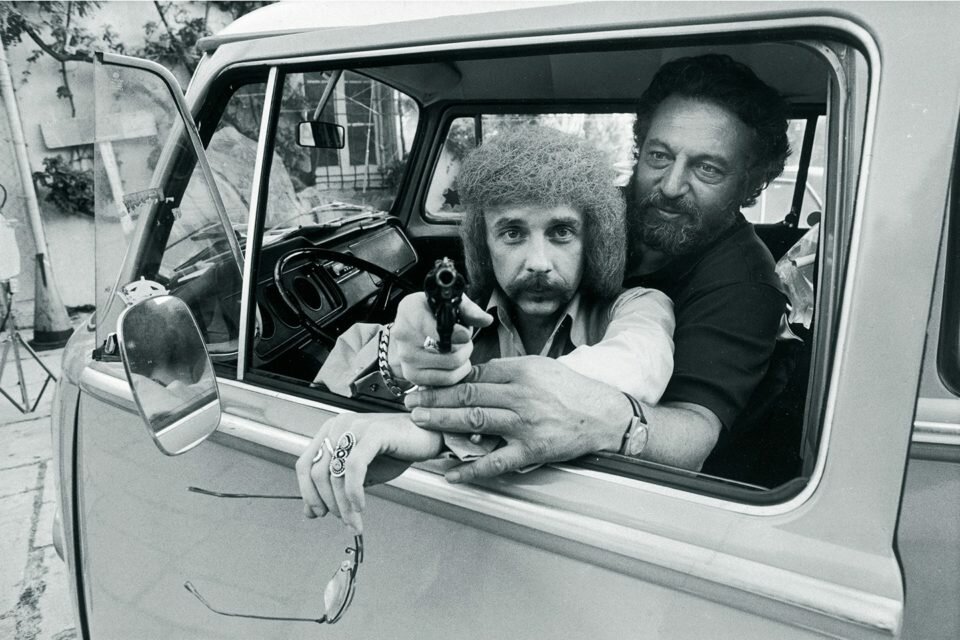

The trinity made up of hippies, drugs and arms would have its most famous example in Quicksilver Messenger Service. No one can deny Frederic Remington’s bloodline on the cover of his second album, Happy Trails, from 1969. It’s also a well-known fact that one of his guitar players, John Cipollina, was a gun collector, and in their first years the band lived in a rented ranch in Point Reyes Station, with horses and cattle, playing at being cowboys and loaded with iron. In the vicinity, the Grateful Dead had founded a settlement, and if the Quick defended a return to cowboy-frontier culture, García and his crew preferred to preserve the Native American legacy. In his book El rock ácido de California, journalist Jesús Ordovás narrated this episode: “The Dead took a lot of LSD; one day, in the middle of a trip, they decided to attack the Quicksilver ranch with arrows and hatchets, leaving them there tied and gagged. As revenge, the Quick planned to attack the Dead at the Fillmore. But they did it on the day that the police had murdered a negro, and the Fillmore was at the centre of the ghetto. As soon as they appeared, ten masked and armed freaks, all the Frisco police jumped on top of them.”

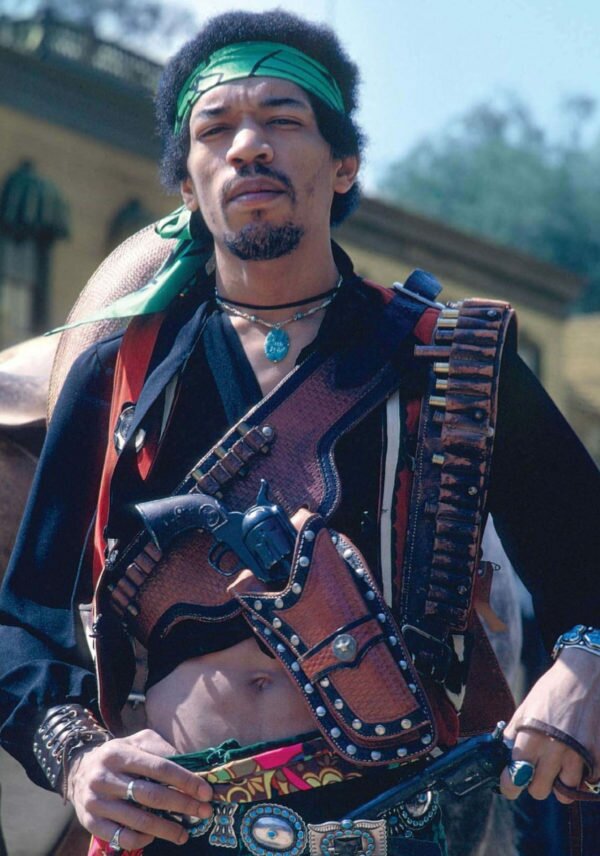

Many are the references to homologated weaponry in a genre as kin to detonations as rock, starting by the name of many bands: Gun Club, Sex Pistols, Celibate Rifles, Parabellum, 38 Special, Guns & Roses, Thee Michelle Gun Elephant, Comando 9 mm, etc. No less numerous are the songs referring to the topic, beginning with Billy Roberts’ , in its most universal version: “Hey Joe, I said where you goin’ with that gun in your hand/oh I’m goin’ down to shoot my old lady/You know I caught her messin’ ’round with another man”. Aerosmith launched the single , which described the way in which a teenager girl stopped her father’s sexual abuse: “She had to take him down easy and put a bullet in his brain/She said ’cause nobody believes me.” In their first album, the Flamin’ Groovies included a version of , also interpreted by Bing Crosby and many other artists, which advised not to put an armed woman’s jealousy to the test: “Oh, she kicked out my windshield/And she hit me over the head/She cussed and cried and said I lied/And she wished that I was dead/Lay that thing down/Before it goes off/And hurts somebody.”

To kill or be killed

In , Lynyrd Skynyrd, authors too of and , dedicated an ode to the revolvers popularly known as such in the Us, small and cheap guns responsible of many hot reactions: “Mr. Saturday night special/Got a barrel that’s blue and cold/Ain’t good for nothin’/But put a man six feet in a hole”. The Clash symbolised terrorism in a Thompson machine gun, main topic of : “you’ll be dead when your war is won/tommy gun/but did you have to gun down everyone?/I can see it’s kill or be killed.” On their behalf, referred to Jamaican gangsters and to The Harder They Come due to the police repression in that south London borough, taken by Caribbean immigration: “You can crush us/You can bruise us/But you’ll have to answer to/Oh, the guns of Brixton.” A third shot at the floating line of Power was done with : “Guns guns a-shaking in terror/Guns guns killing in error/Guns guns guilty hands/Guns guns shatter the lands/A system built by the sweat of the many/Creates assassins to kill off the few.”

The mortal results of a failed robbery that ends up with the life of the robber, a white student, and the robbed, a black shop assistant, were the main theme of by The Scott Morgan Band: “One night Billy walked in/with a gun in the heat/got a taste for drugs/he just couldn’t be beat/Johnny opened the till/just like my man said/but came up with a pistol/and now both lay dead.” Owner of a Magnum 44 -the shoots of which can be heard at the beginning of , which also featured , co-written with Springsteen, another artist with several gun songs-, Warren Zevon included in Excitable Boy the piece Lawyers, Guns and Money, the odyssey of a rich family’s son looking for trouble: “I was gambling in Havana/I took a little risk/Send lawyers, guns and money/Dad, get me out of this.”

Point-blank

Five times have AC/DC resorted to guns: , , , and . Iggy Pop saw them in his Oedipus-like dreams, as he confessed in : “You know I had a dream last night/Mother was in my bed/And I made love to her/Father he gunned for me/Hunted me with his six gun.” Before such an avalanche of references, one might ask how many musicians have never ever sang in praise of guns but still have broken the hypocritical position that the rock industry traditionally adopts to openly express its support of free possession. Krist Novoselik from Nirvana is one of them: “They’re good tools when you live in the country, with them I can protect my family and my home. They’re perfect to scare away the raccoons and coyotes coming for my hens. In any case, if I had problems with people the first thing I would do, would be to call the police and wait.” For Eric Clapton, owner of a valuable collection of not very common weapons, the humanistic properties of these are unanswerable: “Shooting guns has taught me to relate with other fellow humans.” The most pompous of their defenders inside and outside the rock arena, Ted Nugent, is very well-known in the gun rights circles and as a hunting champion. Thus, we won’t insist in reproducing here his declarations, on the other hand developed at length in the book God, Guns and Rock & Roll.

It would be interesting to read the opinions of those who in the pop sphere suffered the consequences of that permissiveness that, according to Nugent, make their country a better place, be it by their own or a third party decision. For instance, suicides like Joe Meek, Del Shannon, Kurt Cobain, Paul Williams from the Temptations, Bob Welch, Wendy O. Williams and, potentially, Townes Van Zandt, keen on playing Russian roulette with two or more bullets. Or those whose opinion never counted… Felix Pappalardi, bass player for Mountain, was shot point-blank by his wife; Sammytown, the leader of Fang, was shot by a robber; Larry Williams, the same one that used an iron bar to claim the money Little Richard owed him on coke, was found dead in his house with his brains blown by no one knows whom; founders of Iranian-American band a The Yellow Dogs, the brothers Farazmand were also shot dead in a Brooklyn bar.

The last bullet

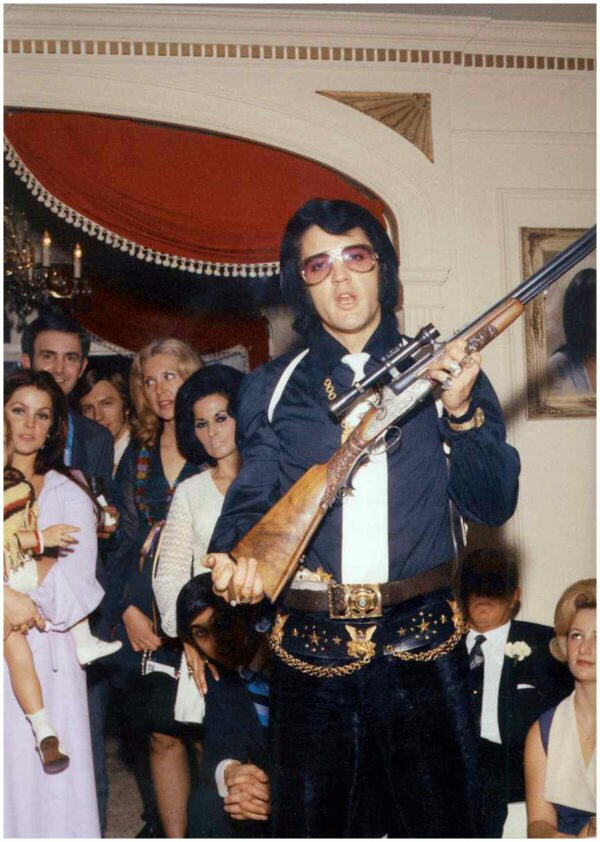

Elvis shot his TV set when out of his brains in pills was unable to tune the channels at the late hours. Mysterious, to say the least, was the disappearance of the gun with which Richards threatened a biker, while the Stones recorded Exile on Main Street at the French Riviera, so that he couldn’t be charged of anything. It didn’t happen the same when Grace Slick from Jefferson Airplane decided to aim at a policeman. Another chapter entirely should be devoted to Phil Spector. In 1958, while on tour with The Teddy Bears, some thugs attacked him in a toilet, peeing over him. Since then on he would never travel without a gun or a bodyguard. Rumour has it that at least in four occasions guns interfered with his work. Off his head in amyl nitrate, during the recording of Rock’n’Roll, he shot a gun very close to John Lennon’s ear just for fun. Then it was the turn of Leonard Cohen with Death of a Lady’s Man; drunk, the producer showed him his love aiming at his neck while he told him, “Leonard, I love you”. Debby Harry went to the Spector mansion to discuss a possible production, but the topic of conversation always derived towards the 45 calibre with which the host aimed at her shouting, “bang, bang!”. End of the Century ended up being almost a real fin de siècle for the Ramones; covered by a vampire cape and with dark glasses on, Spector convinced them that they should record the same song for the hundredth time at gunpoint. Spector gave the master touch to that Wall of Guns in 2003, peaking his gun delirium by murdering actress Lara Clarkson, for which he’s still in jail.

The wisest readers will have noticed that I’ve avoided mentioning genres much keener on shootings than the ones developed here, that is hip hop (from Public Enemy to the real and metaphorical victims of gangsta), heavy metal, salsa or narco corridos. Precisely due to their productiveness, and our sickness of it, I leave this to more expert hands on the matter should the audience require it so in the future. For now, we have emptied enough barrels.