Cthulhu is pop. H.P. Lovecraft’s monster representing cosmic horror now has its own GIF version, emoji, etc. Alexandre Serrano can’t believe his eyes.

David Peace:

Maldito United [The Damned Utd]

Ed. Contra

BRIAN CLOUGH’S STATION IN HELL AND THE DAWN OF FOOTBALL

BY ALEXANDRE SERRANO

In 1974, Brian Howard Clough had already performed several miracles. In six years he had taken grim Derby County from the deep end of England’s Football League to their first Premier League ever and even to the Champion’s League semi-finals. Along the way, though, he had developed an almost pathological antagonism towards the dominant team at the time, Leeds United.

Clough had gone a long way to proclaim himself the moral and football antagonist of anything that “fucking filthy Leeds” represented, one of the toughest and more quarrelsome teams to ever step on a stadium. That’s why it’s so surprising that when Leeds had to replace their beloved manager, Don Revie, when he was leaving to train the English national team after thirteen seasons in the club, they chose Clough. And what’s even more surprising was for him to accept the job. But don’t think he did so eating his previous words up. As soon as he met his new and suspicious pupils, he called them up for a meeting. His conciliatory words have become legendary: “All right, gentlemen, gather around, please. Well, I might as well tell you now. You lot may all be internationals and have won all the domestic honours there are to win under Don Revie. But as far as I’m concerned, the first thing you can do for me is to chuck all your medals and all your caps and all your pots and pans into the biggest fucking dustbin you can find. Because you’ve never won any of them fairly.”

What took Clough, an intense and garrulous guy obsessed by victory but always chased by the ghost of failure, to accept that poisoned present? And why did he undertake it with such a suicidal mixture of revenge, recklessness and megalomania so that he was kicked out just forty-four days later? Those are the questions that The Damned Utd, David Peace’s novel, tries to answer. Recently translated into Spanish by Editorial Contra, it has been fairly saluted as one of the greatest sport books ever written. And although it’s true that the story can provoke the typical suspicions of any work taking a real figure and pretending to talk on his behalf –The Damned Utd is presented as fiction, but is told on the first person-, the truth is that it paints a convincing portrait of a character who acquires mythical proportions thanks to his unstoppable and quixotic tendency to end up in tricky situations, his mixture of insolence and vulnerability and his as incontinent as sharp mouth.

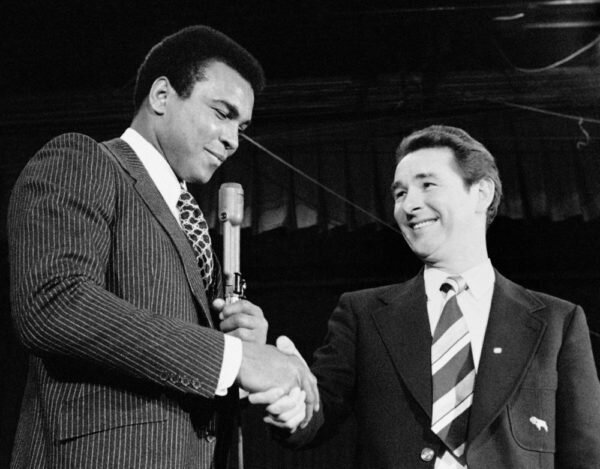

Clough seduces, obviously, for his authenticity, but also due to some of the contradictions he embodied. A guy who didn’t give a toss about hurting anybody’s feelings -when, after a salary increase, he was told he would be earning more than the Archbishop of Canterbury, he replied that maybe it was because he saw “Derby County’s arena full and churches empty”-, used to complain about his own team’s supporters: “they only sing when we win. They’re an abominable bunch;” manage stars and egos without today’s prudish precautions: “if you were a racing horse you would have been sacrificed already,” he told prone-to-injuries player Eddie Gray; and take political sides: “Are you a superstitious man?” a journalist asked him soon after he started training Leeds. “No, Austin. I’m a socialist” Clough replied. But at the same time he was a forerunner in some of the most slippery contours of today’s football world, such as media over exposure or the aggressiveness of the transfer market.

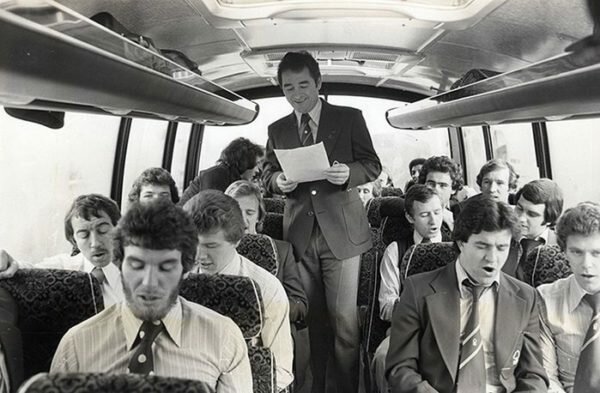

Probably the most seducing aspect of The Damned Utd might not be on its surface, Clough’s vibrant and hilarious adventure, between epic and farce, in front of a team he utterly despises, but on its background: a landscape which was about to suffer a radical metamorphosis and in which he was at the same time a herald from the future and the last of the Mohicans. When he started as a professional trainer in 1965, elite football still maintained a primitive innocence. It was still a popular form of entertainment in which players changed their clothes inside abandoned train wagons at the door of the stadium, wore the opponent team’s second shirts if their kit man forgot theirs at home, played bingo during pre-match meetings and hid ashtrays in changing rooms in case they needed a smoke before jumping on the field. And managers were those guys who both picked them up in their own car to take them to the training sessions and appeared at their homes to convince them to sign for their teams: “The only agent back then was 007 and he only fucked women, not whole football teams,” he remembered when he retired in 1993, coinciding with an accelerated commercialisation of the Premier League: the appearance of great sponsors, millionaire contracts for TV rights, and the definitive democratisation of the audience. The beginning of a way that has ended up in petrol-directives, stadiums with airline names, mega expensive tickets for rich tourists and the adaptation of match schedules to China’s prime time. An era in which Clough, so witty and innovative in many cases, couldn’t but be part of a romantic past that was already over. His opinion regarding the excess of televised football was that “you don’t want to eat roast twice on a Sunday,” and about the new era’s icon, David Beckham, that “he has a wife who can’t sing and a hairdresser who can’t cut his hair.” A proud member of the working class and very thin-skinned when it came to aesthetic dignity, he would have had a massive stroke should he had seen the parade of mohawks, poses, tattoos and caps preceding each match today.

Because football, in its rise to become the most universal form of entertainment, has had to pay the price of becoming denaturalised and of sacrificing its old roots and traditions. Today it’s a global cultural phenomenon, but also (and probably due to it) a place more and more stereotyped and unyielding to anything that might impede its commercialization. Individuals as wild and unpredictable as Clough have become almost extinct. And there’s where the appeal of The Damned Utd resides: it takes us back to a most genuine past, shows us the meaning that the words character and charisma once had, and what sets those qualities apart from the opportunistic histrionics taking their place nowadays. Maybe we shouldn’t get so gloomy about it all: at the end of the day, it’s only football. But it’s also very possible that the form that the most relevant of pastimes adopts and the characters it produces within an age might say something very relevant about it.

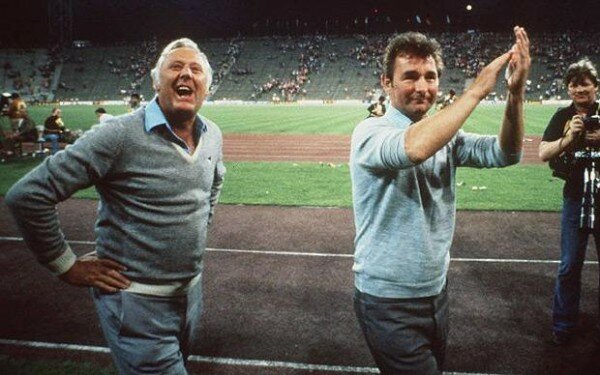

On top of the world. The lap of honour after achieving the maximum feat of his career: crowning humble Nottingham Forest as European Champion in 1979. He would repeat the same victory the following year. By his side, inseparable Peter Taylor, who refused to accompany him on his failed adventure in Leeds.