Fuck everything! There are millions of GIFs to illustrate that moment in which we would send everything out of the window. Joan Pons gives us some instructions of use.

An Interview with Pere Llobera

Blah, blah, blah

(about myself)

by Andrea Valdés

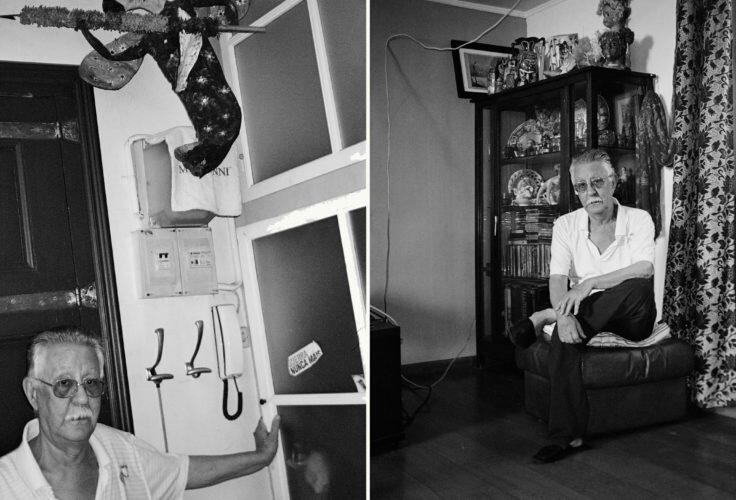

Pere Llobera and a cut-out friend

On a Monday, Pere Llobera (1970), who lives between Barcelona and Amsterdam, the city in which he has exhibited his art the most, invited me to his studio, where he has several canvases, an intervened table or a half-sculpted Cesare Pavese head, author he describes as a butterfly entering a bonfire. After having breakfast together we begin the following dialogue.

Pere, the first thing I saw of your work already caught my attention. They were paintings from the series Una història de mediocritat [A History of Mediocrity]. When I saw them they reminded me of the times you look at old photos with your sister and start saying thongs about the people on them: “Look at him there, now he’s sooo fat!”

It’s exactly that, but what happened is that I was saying it about myself. What was I doing at that dinner party and with that people? I went to university and they saw me as this little painter and they almost didn’t let me talk because they didn’t want to hear about yet another painting. They were a bit shallow. But, on the other hand, their lives were OK for me. I don’t know… They could make me shut up, but if we went to the Bagdad to see a striptease or to Milan for the Champions League final, it was a real party. I had a lot of fun. It was afterwards, when I saw the contact sheets and retrieved the photographs that I started thinking: great, but what did I get from all that? I think I lost some good years of my life and, careful, I don’t mean to sound snobbish, because I really liked the idea of hanging around people that had nothing to do with the arts and was fun, but there were no correspondence between us. There’s only one of them I would still see (and not for long), the one who was my mate in the first place, but he was the one who introduced me to the rest of his bunch. He’s an oyster dealer from Mercabarna, a guy with a good humorous energy. That’s cool. As Buñuel used to say, “a day without laughing is a day lost”. I mean, I’m not interested in people, no matter how culturally sensitive, if they can see things with a touch of humour.

I think that faces at museums look very serious. I have to confess that of all disciplines, visual arts are the ones that make me feel more insecure. I feel I need mediation. I let myself be guided by people I know and other artists with whom I might have something in common in other fields, as if I depended upon their reaction to start reacting.

Well, you shouldn’t feel like that, especially you, who like reading so much. Let’s see, how to explain this to you without sounding bibg-haeaded… When I go to see an opera, for example, I know exactly what to shit on (laughs) and I’m no expert on the subject, but what I don’t like, I don’t like. If you know how to discriminate, why not doing so in a museum? Besides, visual artists are so dense, most of their work is supported by readings, essays…

Yes, that’s why they interest me, but sometimes I prefer buying the catalogue and reading it at home. I don’t always feel the spatial layout is justified.

Most of the times it isn’t. To be honest, I ended up in visual arts and I don’t complain, but when it comes to trying to transmit something, sometimes I think I should be a musician. There’s something in visual arts that I don’t think is as powerful as it is in a good song or in a very good book.

That surprises me, because one thing I see in your paintings and that I feel less in music, although I’m not saying it doesn’t happen, is their abstract dimension. Despite being a figurative painter, there is something psychichal, like a malaise… I don’t know, don’t get angry, but I see a bit of a dirty mind.

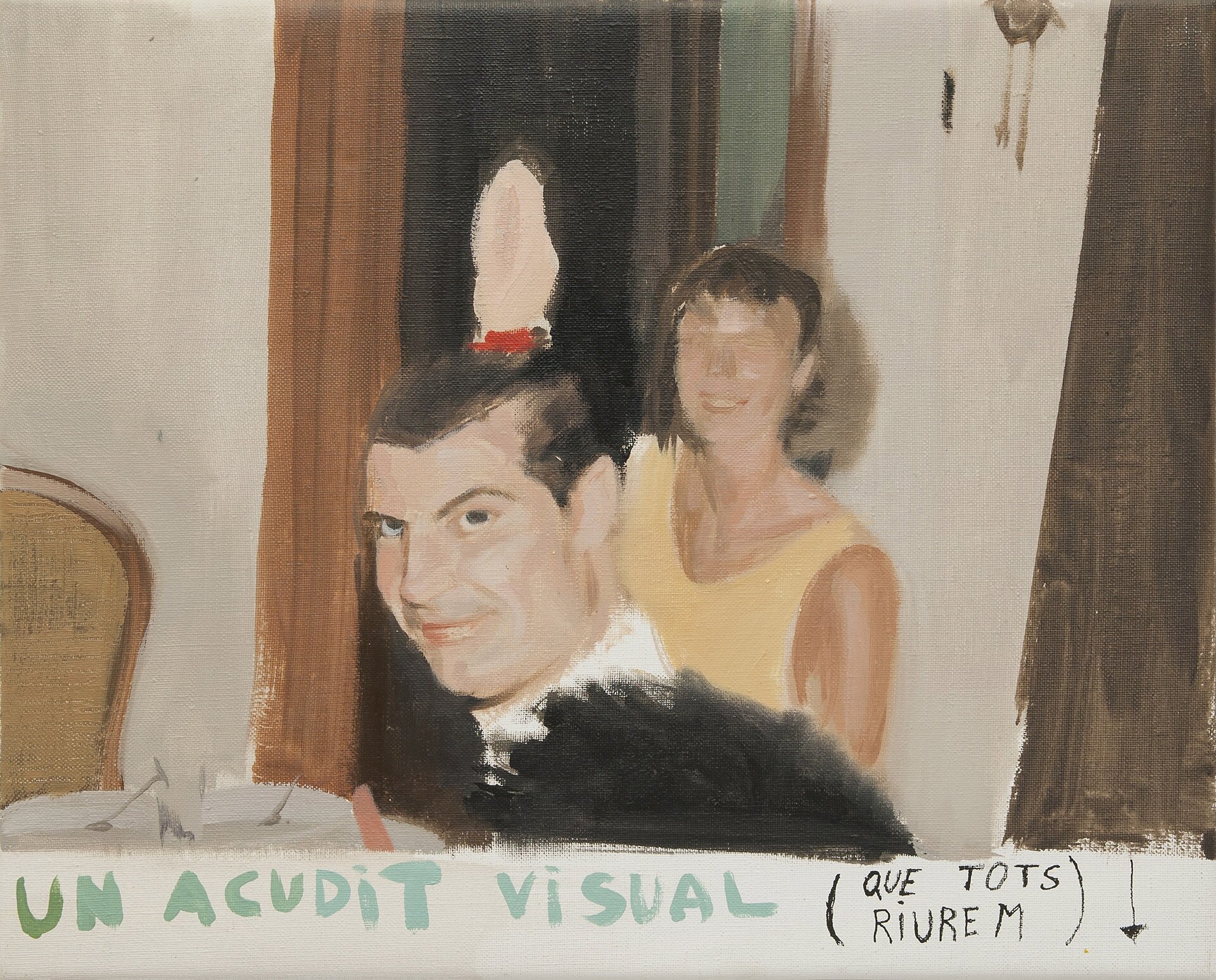

“The painting I affronted with the comic tear was entitled Tienda de barreras [Barrier Shop], but maybe I should change it”. 63x70cm oil on canvas (unfinished)

There’s no art without conflict. Sometimes I like saying things like that, big sentences that create an echo, to see if they can stand the passing of time or else they lose punch and end being something silly. After saying them I feel hollow. Have you tried?

At all times! What you were saying about conflict, I call it the urgency to do something, even if it turns out badly, because there’s also certain beauty in failed works, don’t you think?

Totally. Having ideas is quite easy. I have a friend, a former landscape painter who now builds his own guitars, who I sometimes see during the summer holidays, and in order to have a laugh, or just by chance, we start thinking about this “ideas” that could be the main work of some artist. It’s what happens when you sublimate an idea, you might end up with a piece. You think it would be fun doing it, Damien Hirst style. If you have the money and twenty guys working for you…

…You end up with a bloody shark in a formaldehyde tank! But who wants that?

I think what really makes you discard an idea or not discarding it, what determines whether it’s worth it or not, it’s whether there is a piece of you in it. It’s that simple, because if not, it’s just an idea and, to me, that’s the key point. If it can answer the question of what of you is in there, or as you say it, the urgency. There you have the first letter from Rilke to the poet… Do you really need to do it? This might sound a bit romantic, but I didn’t start painting from any other place than that. In my paintings I always ask myself whether, beyond the idea, the person behind it is interesting. And when it comes to other people’s work, if that someone is giving you something, he’s giving himself.

I think that in your paintings, not only we can glimpse that question, but also the fact you’re worried about it. There’s something not very relaxed. Does that make sense? I do see that. And I like it because I think that the most beautiful thing is when an artist defends his area of insecurity, his not being too sure whether he should be doing that or not; to sum it up: his fear of screwing up!

You’ve nailed it: if I am something at all, is not very relaxed. It would be impossible for anybody to hypnotise me, because I immediately begin competing with the hypnotiser! Also, in the tube, I can always spot thieves: we work in the same frequency. If we cross each other, either I look down or he gets off the train. Once, my wife and me saw a guy on a motorbike and I said: But how is he leaving his helmet like that? And she said: What’s wrong with it? I answered: They’re going to piss in it! You should have seen her face…

I can imagine! There’s one thing I find very moving in your text for Una exposición luminosa [A Luminous Exhibition], that I think you curated yourself: in the credits of a painting called Balbino you openly say sorry for not contributing to the world with something more positive. Have you ever tried painting a cheery painting?

All the time! At the studio I have a project that it’s renovated every year. It’s called “change your palette, change your palette…” and find inspiration in Mike Kelley. Do some pop art, basketball mascots and that sort of thing.

Mascots? That sounds horrible.

Well, obviously, if I did them, they would be horrible, but I force myself to. Sometimes, when boarding a plane I see all those people reading or sitting with their family and I think, “why can’t I just be like them?” I’m not talking about naive people, but people at ease wit the world, who despite knowing how everything is, still want to go on. They’re charming people, and even if I already have a voice and I cannot defeat it, I’d love to polish my neurosis, try to be a different way, like Philip Guston did. I’m not a big fan of his paintings, but I like his life project. I’m talking about becoming popular painting in a given way and in his last ten years completely changing his style. Goya did that too. At the end of his life he decided to guide all the power of what he had been in another very pure direction.

“This drawing has no title. I got it off a book of drawings by Francisco Goya in which you first saw a lady looking herself in the mirror and seeing a monkey, and then a skeleton holding a mirror that fell on it and at the end this drawing, which depicts a mirror that sort of has become a mystic portal. I also associate it to the song Lucha de gigantes [Giant Fight] by Antonio Vega”

I know you’re going to tell me that is too early, but how would you evaluate all you have done up to now?

Until I was twenty-five, it was all shit; too many landscapes. I had such a visual hunger! I ate everything, no discrimination. It was an “all you can eat” deal; an executing hand, like the one in The Addams Family; an executing hand and no head.

(Laugh) And what about what you do now? Do you like showing what you do?

I’m a shameless person. I don’t give too much importance, for instance, to the fact that you are interviewing me. I prefer looking at it as you and me talking, or going for dinner together. I’d almost say that to me dinner would be an art format in itself.

I like the idea of one sentence taking you to the next one and so forth, because nobody knows where a dialogue might take you. There’s a certain resistance to order. I don’t know whether you’ve read César Aira’s La prueba [The Test]. Since I did, I keep on dreaming about this terrible idea of writing a monstrous dialogue, like forty pages long, with some jokes thrown in, with threads that get lost and moments of great beauty, but you need to be an absolute master of the language for it not to be a bore, because there’s no plot to stick to.

Do you know who’s a bit like that? Imre Kertész. He’s one of my favourite writers.

Do you recommend him? I’ve got to confess that I can’t take all that Jewish thing at the Acantilado imprint. One day I said: that’s it; I’m done with barbed-wire literature.

But Kertész is a cold fish. Even if he was in the camps, he lives it like something he doesn’t want to dwell on, something he didn’t choose. It’s a bit like me trying to change my colour palette. I realise the comparison is a bit frivolous…

(Laugh) The way we equalise traumas is fascinating! Palette = Genocide.

What I mean is that in his writing, that condition is like a knapsack he tries to get rid of. He keeps on moving his shoulders, but doesn’t manage to. If you want, there is a process of stylistic identification. Then he also has some controverted stuff, he’s a weirdo, like when someone makes a typical Jewish comment at a dinner party and he becomes very nervous and leaves. It’s the beginning of Kaddish for an Unborn Child. He makes such a racket in the book because he can’t stand the trite phrase “Once more, Auschwitz is inconceivable”. The funny thing is that, while he leaves the scene he keeps on thinking, he just can’t stop. It’s a huge flow. The novel keeps on changing places, but it talks to you all the time. Scenes go by, like in those old films in which the backgrounds seem to slide from a roller and it’s the character the one that is still. It’s a curious effect.

What are you working on now?

In an exhibition I just cannot do without David Armengol. The idea is defining a bit my body of creative work and make it solidify in a proper place. Let’s see if we can manage, but meanwhile we’re preparing the scaffolding of what we want to show. It will probably be entitled Faula rodona [Round Fable] and it tries to defend … (He stops to think). I like the fact that I’m finding difficult to explain it. Maybe I need to set it up in a space to see it clearly.

Do you know how many pieces you will show?

One is very clear, at least today, because I always change my mind from one day to the next. It’s called Record sense veu [Unvoiced Memory] and more than a painting it’s an idea that is asking for images. It’s from a moment that nobody recorded, from when the Gong band played at the Monsterrat abbey. They came with some hippie friends who the previous year had slept there thanks to a priest called father Francesc, who decided to take them in.

Gong in Montserrat… Are you sure about that?

Yes, yes. They were disguised as magicians! It was 1973. I’m not very happy with this version of the painting I’m going to show you now because it’s too literal. I will do another, and maybe on the third one… In this case I’ve got faith in the painting still to come. It should be less narrative; maybe with the canvases falling off and no central object, as if in the painting of the infantes by Velázquez you took away the infante.

But what are you looking for exactly? What’s the urgency here?

I think this has happened to so many people, but in my case… Well, it’s me wanting to go back in time, having a life, and not being able to. I think I shouldn’t be here, and I’m not taking about some shabby nostalgia, but of the feeling that my abilities do not fit in with our times.

And do they with some other times?

Yes, yes, very clearly. The seventies.

When you were born.

I’m a clear broken rubber case. My brother is twelve years older than me, and what I lived at home, what I saw from my brothers, was a parameter for me. I’m talking about something real, not a romantic projection. I mean: I was in my sister’s room listening to Patti Smith.

I get it. I’m also the youngest and I think my sister’s choices, with whom I shared a room, had more impact over me than herself. All those folders and walls full of pictures o actors, the Brooklyn bridge… What a high!

Isn’t it? Look at those precocious actors that sing and dance perfectly. They’re monsters because at that age we’re extremely able to absorb stuff, we’re capable of anything. I’m not saying we were children prodigies, but we were very sensitive to what surrounded us, and what I got was tuff from that time. I’m talking about a kind of wild attitude that left a great impression. Going back to the show, I’d like it if under the appearance of tranquillity of what I paint people could perceive that energy because, as you said before, I’m a tense, and I’d almost say aggressive, guy. The other day Soraya Saénz de Santamaría was on the telly and I threw a lump of bread to her, just like that, instinctively.

And why would you say you react like that?

Maybe my life hasn’t been so satisfactory. Let me make myself clear, I’ve had a comfortable life. But even if at home we didn’t lack anything, things weren’t done exactly well. Just to give you an idea: my parents bought a piece of furniture for the living room, but since the TV didn’t fit in there, that TV ended up in my room, so, at home, if we wanted to see a film, they all ended up in my room, sitting on my bed. Like that who’s ever going to have a studying routine? I was a bad student and I took refuge in drawing, because it’s what I did best, and there’s some kind of unfinished person issue in there…

In one of your paintings, called Dad’s Car, there’s a car inside a car wash, but in the windows there are images with that snow from when TV sets didn’t work properly…

It’s a bit the trite idea of childhood ending and that there’s nothing beyond your father’s car, but it comes from something I read in a Žižek book. It’s called Looking Awry, and if I remember correctly he comments an episode from The Twilight Zone in which a couple riding a car is trapped in a village.

Žižek. You don’t like your times, but looking at what you paint I’m not sure it could belong to any other.

That’s because I don’t live it in a sick way. I mean, I’ve not remained in the past. I’m not that stupid. But, in certain occasions, I need to open a door in my head and enter there, spend a while before getting back to real life: the children, their food, the house… My paintings are like doors. Well, I want them to be, but I never quite manage! It might sound very pretentious, but I want to paint places, paintings, in which I can stay. It’s the same that happens to me with Friends. I’d like to live inside that TV show.

(Laughs) Really? For me, apart from Back to the Future, it’s Hitchcock films. I know it sounds weird, but I get this in particular with North by Northwest. It’s a place I always like to re-visit. Whenever I can’t sleep or I’ve come down with the flue, watching it calms me down. Maybe it reminds me of watching it back home, with all the family in front of the TV set.

Dad’s Car, 40x50cm, oil on canvas, 2011

If you think about it, it’s crazy! Wanting to live inside a painting, building a perceptive door and all that… It’s impossible, but that doesn’t mean I don’t want to do it anyway. Have you ever played at stopping the sea?

How do you play?

Very easy: you stood in front of the waves trying to stop them until you ended up knackered! I used to love doing, no matter how absurd it was! When I paint it happens to me: you want to transmit something to someone, but when you try to put it on canvas it’s already rotten.

This reminds me of an artist you told me about that I like a lot: Bas Jan Ader. Especially when he wants to reverse the direction of the conquest and travels in a little boat from the new world to the old continent. The fact that he got lost and that he called his project In Search of the Miraculous is like a weird joke.

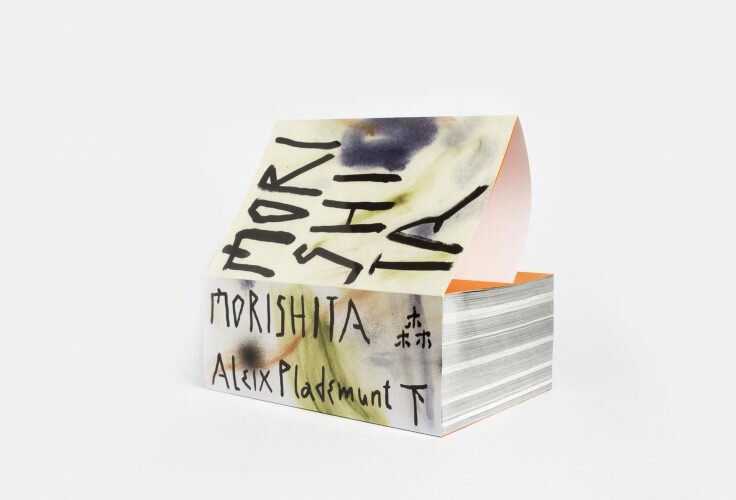

It’s a bet that takes you to an extreme. I’d like to think that he, the son if a preacher who died in WWII, didn’t go out to the sea to commit suicide, but to keep his promise. Before departing, he sent a letter so that it arrived to his gallery, Art and Projects, the day of the opening, after crossing the Atlantic. That would have been precious. He probably thought: If I make it, I purify myself of the life I lead in the US, and if I don’t, it will be my penance. In that sense, Bas Jan Ader, like Mishima, was one of the ones who finish what they began.

I agree, but what I like and what makes it poetic is disproportion, the imbalance between the idea and its implementation. I think he controlled that game very well, almost like a funambulist, because he was not grandiloquent at all. They were all small pieces, gestures, falls… You live that imbalance?

No. I’m a survivor. My madness is more like going to the swimming pool, and spending two hours trying to turn a lighter on with my foot while people wait for me in the water. I finally did it, and that day I didn’t go in the water. It was the most useless triumph, but it completely describes me.

Drawing from the series El mal de Ensor [Ensor’s Sickness]

And where are the rest in all this?

I can’t say the audience doesn’t exist for me. I’d be lying. Maybe there are artists for whom audiences don’t exist and I like them, but I have to adapt what I do to what I am. Even though I value Bas Jan Ader or Wojnarowicz, what they do is no use to me. I have to solve it. Make it useful to me and negotiate with myself. That attempt at negotiation, for example, I had it with a poem by Ferrater.

This is the whole story:

I did a painting called Porros y música en casa de Àlex [Joints and Music at Alex’s Place], which was obviously interesting to no one. In the end, that picture was given to another friend who was in it as a present. He was very please. A couple of years later, when I bumped into him I asked him about the painting. He told me that his partner didn’t allow him to have it on the wall at home (here we have to suppose that the problem was that in the painting he was rolling a joint) and for that reason he had it behind a door, at a village called Ventosas. I loved the whole situation! I mean the uneasiness that the painting could provoke in another person, so I asked him whether I could go to his village and do a painting of my own painting set aside, behind a door.

Painting Behind the Door, 100x70cm, oil on canvas, 2012

I took advantage of the trip to record Ferrater’s poem (Si puc [If I Can]), at sunset, when there was no longer enough light to paint. The idea was shooting the reading in video and recording it on tape and not stop until I had read the poem only and truly to myself. It took me around twenty-five minutes, because during the previous attempts I had the rest of people present in mind and so they sounded unbearably stilted. As soon as it seemed honest enough to me, I stopped. During the recording there can be heard dogs barking in the background and also me grunting when it didn’t sound OK. After a few days, I pressed play on the tape recording machine in my studio and I painted it during the same amount of time I used to recite the poem properly, as if the poem was inside the recorder I was painting. I called it Collir roselles [Gathering Poppies].

Earlier on you’ve talked about doors of perception. When I think of painting, that image of Pollock on four legs or that of Miró losing track of time and half hallucinating come to mind. Do you think genius exist?

The problem is that that word it has a lot of connotations, it’s ugly, but I do think there are very powerful people there, but that doesn’t mean they are in everything they do. Sometimes being a bit crippled can bring about amazing things. For example, it seems Elvis was a bit clumsy, emotionally. Or think about Salieri, when in Amadeus he asks himself, super affected, how is it possible that such a horrible person might create such beautiful music. And he’s talking about Mozart. In that sense, I’m very impressed by Bob Fosse, because he’s like life itself expressing itself through movement. He was a choreographer, a dancer, an actor, a director, a very able man but who questioned himself all the time, and that got me addicted to him. In All That Jazz there’s a moment in which he appears dressed as Joe Gideon, his alter ego, watching a film. Us fans know he’s Lenny. You see him all lost in thought, because he’s editing it and there’s something wrong. Then he says: “Does Stanley Kubrick ever get depressed?” (Laugh) Maybe I’m less empathic to that filmic perfection. I love 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s a refuge, an amazing film, but if I had to choose, in another life, what to direct, I’d go for All That Jazz. It’s pierced by doubt, but what that doubt generates is incredible!

This reminds me of a book I borrowed from David (Bestué) in which John Ashbery talks about minor poets that for him were very influential, even if you could spot some errors or badly articulated moments. It’s called Other Traditions. I like the fact that he defends that second place, maybe because always talking about geniuses ends up being a bit boring.

In this sense, I like Jordi Barba (a.k.a. Pope), a friend of the also poet Enric Casasses. Pope’s work is less known; he died younger. He did very strange things, but I sometimes go back to El crit platejat [The Silver Scream]. I don’t think it’s a hinge poem, but I complete it with the figure of Casasses, for me one of the greats, and since I read it in a very biased way, even more.

Since when are you interested in poetry?

I started late. I come from a hyper-narrative tradition; telling stories has always been there and still is, but I’d like to open up to something different, and I don’t only like poetry, I also find it useful because it favours the free association of ideas or alchemy between two elements. I ask myself up to what point I can translate that in a pictorial level.

You have a painting that talks about Vinyoli.

Yes, but I’m not very happy about it, I thinks it’s very much like Brossa, almost like a visual poem, and that’s not what I mean. We can avoid talking about the picture and talk about Vinyoli, because I’d like to paint some of his poems. He isn’t a minor poet, as Pope is. He’s the kind that sets a precedent and, sometimes, I compare him to others. He’s a nullifying poet. (Laughs) Like when you start reading a writer through his best work and after that it’s never the same. It happened to me with Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis. We talked earlier about Guston or Goya, outstanding artists who all of a sudden project all their power towards something very pure. In Wilde’s case, it’s anger against his lover, while he’s in prison. What I read afterwards, I like, but nothing can compare with that moment.

Are you afraid of finding that in a painting? A cataclysm!

When it comes to that, I’m more practical and live it differently. It’s not like when I read. For example, when I was in Holland, I lived that “bad painting” thing; I mean painting badly on purpose, with acid colours. It’s something that doesn’t appeal to me, but that freedom before the canvas I probably synthesize in a different way. As for Goya, to cite but one of those painters that in my case could be a great nullifier, it makes me tense instead; I compete against him because, of course, I want to do that. I tell myself: How to become Goya? Professionalization has that perverse point about milking things. It distorts.

Going on with this bar conversation comparisons, maybe my Goya is Virginia Woolf. Every time I read her I think: Fuck, fuck, I want to be able to do that (laugh). I know: it sounds like I’m crazy, it’s ridiculous…

And why cannot we dream big? It’s like those big classical music concert performers who don’t dare to compose. What did they do to them at the conservatory? I’m against the inhibition of ambition. If anyone asks me where do I want to go, I’ll say: to the Whitney, if you don’t mind. (Laugh) Whether I get there or not, that’s another story. Even if it sounds big-headed, I don’t have the time to think about it, not even to name drop all the painters there are right now… I have huge gaps when it comes to visual arts and painting, because as soon as I see something that I can use as a resource, I start working at once. I don’t keep on completing, compulsively. With a hyper-tense personality such as mine, this thing about keeping folders with references is too dizzying. I prefer to concentrate in one thing. On top of that, I think that with such a big visual hunger, you can end up behaving in a disoriented manner. In my case, my ability as a painter made me go with a flow, but one day I clicked: “I shouldn’t use this hand, I should have projects”. Or I had to stop being a slave to my technique because I discovered I could work in many other ways (now like Goya, now like Ader, now… ) and it was madness. I gave it a name: The Ensor Sickness; it’s when you can’t make a decision about your voice, but I closed that pathology with an exhibition, two years ago. And now I’m more centred. But that sickness exists. I’ve seen it in films and above all in shop windows: putting things together that don’t even combine just because you can.

Balbino a medio borrar [Half-erased Balbino] (unfinished), 200x200cm, oil on canvas

Why do you make models of the contents of a painting and then you paint them? Aren’t you doing the work twice?

Painting from an image bothers me. Many of us artists are subsidiaries of that discipline, and it’s so obvious when you paint from a photograph… Convenience has won the game or what? If I paint in the open air or I make models is precisely to run away from that convenience. For example, here I have a painting with a river and a sheep, a tribute to Jan Van Eyck. The first version I painted it from natural, a tiny one. The problem is that I couldn’t take the big one to the place. Lorry drivers blow their horns, if there’s wind, with a 1,70 m canvas outside you end up flying away with it… Painting au plein air is a pain in the arse, but the result is different because you don’t paint with the tranquillity of looking at a picture in your studio. Another thing comes out. Always.

A photograph is also a decision already made. On the contrary, while you look out there your mood changes, the landscape is always being created, right?

Totally. In any case, the ideal thing would to not have to hold this debate any longer. Escaping the purely figurative and the dilemma of whether using a model or not, because it’s really stale. Other goals, such as changing your palette, can make you depend less upon “reality”. In that sense, I love Buñuel, for that carefree attitude he had towards his work, I mean technically. The power was in his head.

It’s funny: in your paintings there are a lot of waste, and that’s something I associate with Catalan. Brutícia, trencadís… But in this conversation you’ve mentioned Goya, Buñuel… several times and then you also made that revisitation of the Meninas with boxes.

I’m a very Spanish painter, as Spanish as you can be. A “paleta brava”. This comes from one of my exhibitions that Juan Francisco Rueda wanted to do. Goya, Velázquez, Ribera, they’re all in my head. Tenebrism. Then that thing about guilt, very Catholic. Although I’m making this up as I go along, talking with you. It might be nonsense. In any case, I dwell on that label. If I could choose a painting to have at home I’d choose Goya’s El pelele. It’s very educational.

Really?

Or I might pick up something much more contemporary, like David Hammons’ photograph of the snowballs, although it’s been reproduced a lot. It’s a beautiful, ephemeral piece and it’s a kind of critique, it doubts the value of things, including art. I like it because I’d never be able to do something like that. Hammons is a personality balancing like plates over Chinese sticks.

I was surprised to know that a guy like that, someone who does such fragile things, so borderline as you say, has had his opportunity or slot in the history of art. He’s had a weird luck.

No, the weird luck is being in New York, at that time. That guy in Cuenca would be the madman of the village, the lunatic that picks up hair from the hairdresser’s. In Cuenca he’d be dead and in Burkina Faso too because they don’t have time for that. But in New York, which is an archive of eccentrics, he had his space. I don’t know if it’s due to boredom, or because people try to find their piece of purity and they end up doing something very crazy, but crazy in a sense that I like. Do you like that city? I ask everyone who’s ever been there.

Why?

Because I’ve never been there! And now my girlfriend wants us to go with the kids. The problem is New York is the city I would have liked to have visited in its most punk moment, with all that seventies brutal effervescence, but I doubt there’s anything left from that and I’m not sure travelling to a mirage will be good for me. What do you think?

It depends on what you think about trips. If you’re tense, maybe you see yourself going round in circles, waiting until you get hungry. If you don’t know exactly where you’re going, travelling can end up a bit like that.

In the end there’s always that moment… But, what am I doing here?

Collir roselles [Gathering Poppies], 2012, 18x14cm oil/canvas on plank