Drake ha hecho un videoclip sobre recibir un tartazo en la cara, Child’s Play. Tyra Banks es la lanzadora. Y Ben Tuthill el testigo.

ESPECIAL

LECTURAS Y AGOSTO

Texto por Ben Tuthill.

WRITING

BEFORE

THE LYRIC

VIDEO

4.

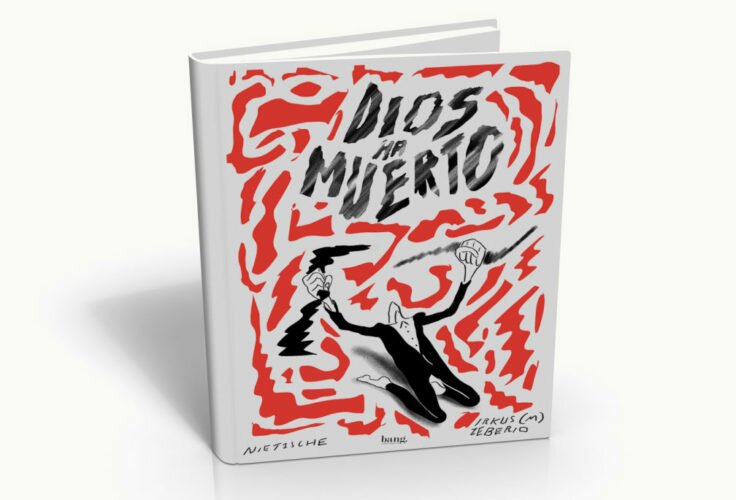

Una palabra también es una imagen. Un signo. Un adorno, incluso. ¿Una nota musical? Para Ben Tuthill los videoclips que explicitan la letra de las canciones son casi un microgénero. De la ultraliteralidad a la textura tipográfica, pasando por el karaoke.

I have a friend who refuses to watch music videos. She doesn’t want someone else’s visual interpretation spoiling her experience of the song. Given the central real estate that music videos occupy in my mind, this makes for a rather trying friendship. But her point is overall salient – it’s hard not to hear a song through the experience of a memorable music video. I’m always going to hear Single Ladies in . I’m always going to hear Bound 2 on motorcycle. The video mediates the audio and disrupts our experience of the song itself. It forces us to read the song instead of just experiencing it.

I don’t think my friend is alone in her sentiment: there are plenty of purists out there who perceive the visual element of pop music as a perversion of musical integrity. We don’t like to read; reading isn’t real.

It’s worth asking how we got to this point. How did we come to so distrust the visual component of pop music? It’s not as if all music videos alter the supposed integrity of their songs. While there are some visuals that add unexpected layers, others that deliberately contradict the song, and others that apply altogether unrelated meanings, for the most part music videos do their best to represent the song in a way that doesn’t distract from the music. Sometimes that truth translates to astounding literalness – anyone who’s spent a sick day watching CMT, for example, knows that country music videos are on that are . The same goes for performance videos, which attempt to display the song exactly as it displays itself in real life (The Replacements, of course, took this to ). We want our visuals to represent the integrity of the song, and for the most part they do their best to appease us.

The most literally literal audiovisual genre, of course, is the lyric video. Lyric videos took off with the rise of YouTube – you could just leave a black screen for a fan-uploaded video, but you might as well fill it with something interesting. Sometimes that’s a bunch of pictures of badly rendered album artwork. . But most often it’s the lyrics themselves. Someone along the way decided that these videos must be profitable, and now you’re loathe to find a major-label single whose release isn’t accompanied by an official lyric video (sometimes these lyric videos are than the official videos themselves).

Lyric videos feel like a bit of a perversion, but they’ve been around since the start. might not be the first music video, but it’s the first good one, and it places lyrics at the forefront. Subterranean Homesick Blues is after all a song about mastery over words, and D.A. Pennebaker’s video it’s Achilles-dragging-Hector victory lap.

Dylan’s placement of the word at the center of the video is a solidification of the act of reading as the heart of the song’s experience. This is the essential philosophy of lyric videos – printed lyrics, unlike other visuals, aren’t additions. They don’t add anything to the song – they clarify something that was always-already present. You don’t walk away remembering the image of the words on a screen, the way that you remember a GIF-worthy hair flip. You remember a clarified experience of the song, an experience that was already there, just buried under idiosyncratic pronunciation and production. The lyric is an exteriority that’s an intimate part of the interior.

Jacques Derrida, riffing off Kant, calls this exteriority the ‘parergon‘, that which is “against, beside, and above and beyond the ‘ergon’ [work]”. The parergon isn’t merely exterior to the work – it “touches, plays with, brushes, rubs, or presses against the limit and intervenes internally only insofar as the inside is missing”. For Derrida, there is no work without the parergon. The things that we experience as “outside” the work are the entirety of the work itself. There is no outside-song. There is no song at all, just phenomenon that mediates itself into existence by separating itself from everything that it’s not.

Derrida had no love for pop culture, but there’s not much out there that provides more of a playground for his Deconstructionist theory than pop music. To experience a pop song is to experience a series of very obvious parerga: samples, quotations, recognizable voices (and their related personas), genres, dances, chart figures, tabloid stories, and, of course, music videos. Music videos are maybe the ultimate parergon, the bizarre zone where every exterior component of a pop song comes together and radically transforms the experience of a collection of sounds into a comprehensible media phenomenon. Derrida would argue that this is more or less how we experience everything, but music videos make that experience obvious.

Lyric videos would try to sidestep the parergon – to travel via the exterior (the printed word) into the heart of the interior (the purely auditory lyrical word). Lyric videos give us the sense that we’re tapping into the truth of a song, that we’re performing an act of clarification instead of adding a new layer of mediation. But to make that argument is to pretend that lyrics are a more real part of the song than the singer’s face, that the words of a pop song are more integral to its song-ness than the dance that accompanies it.

That might be true in a purely auditory sense – but pop music isn’t and has never been a purely auditory experience. And really, even in an auditory sense, giving preference to the written logos of the word over the sound of the sung word pulls us away from the music just as much as an over-focus on the singer’s dress. singing the chorus to Cherry-Coloured Funk is worlds apart from the written-out phrase . To say that they’re the same is to say that a map of a human genome and an actual human are the same thing.

So, back to my friend who doesn’t trust music videos. Derrida would be forced to agree – a music video ruins the integrity of the song (“Certainly the adjunct is a threat. Its function is critical. It entails a risk and enjoys itself at the expense of transforming the [work]”). Music videos, dancing, MTV Cribs… All of these parerga are threats to the song. The media storm surrounding pop music is a grave threat to the music that supposedly stands at the center of it. But that storm is pop music – that storm is the whole point. Pop music is layer upon layer of mediation, and plowing through that mediation is the joy of listening to pop music. Like every act of reading, pop music is a violence unto itself. But that’s ok – that act of self-violence is central to the experience. There’s only a pop song waiting to be read.