Every day for seven days, Anna Senno walks between her home and the laboratory to develop one roll of photographs. 7 Days is a performance project reuniting photography and storytelling.

by Anna Senno

Paris, January 2017

A performance project

joining photography

and storytelling

Day 5

7 days,

The anomalous Penny Black.

Every day for seven days, Anna Senno walks between her home and the laboratory to develop one roll of photographs taken that day.

24 frames – she singles out 1-5, which become the basis for her storytelling. Fiction intertwined with reality: a fixed framework with no pre-established content. One roll and one story per day, for seven days, in pictures and words.

Camera: Canon FT QL – 1966-1972, 50mm 1:1.8

Film: Ilford B&W, 400 HP5

Laboratory: Processus, Paris

* A postage stamp is a small piece of paper that is purchased and displayed on a MAIL item as evidence of payment of postage. Typically, stamps are printed on special custom-made paper, show a national designation and a denomination (value) on the front, and have an adhesive gum on the back or are self-adhesive. They are sometimes a source of net profit to the issuing agency, especially when sold to collectors who will not actually use them for postage. Stamps are usually rectangular, but triangles or other shapes are occasionally used.

7 DAYS © Anna Senno. All images and text © 2017, Anna Senno. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used without prior written permission from the copyright holders.

My father says my true date of birth is really May 1st, 1840, which, he claims, would explain my great wisdom since this makes me very, very old. I wish I had something to hold on to, something explicit, tangible – something my eyes could see and my fingers could stroke. But I guess when something is gone it is just gone. I was named after the world’s first adhesive postage stamp, a British stamp. It was issued on May 1st, 1840 and brought into use six days later. My first name is not just Penny – it is Penny-Black. I removed the dash when I turned eighteen. I now just go by Penny Black and people think Black is my surname, and that is all fine by me.

I do not know what happens to people when they are faced with having to name their child and it is like they all of the sudden get this chance in life to project all their obsessive fantasies or romanticism to their clueless infant. In my mind it is a very unfair confinement they impose, and very hard to eschew. My father is not a collector of stamps. He is a collector of inventions and concepts that he considers have rationalised human life. He collects them in his mind. That’s all there is to it, he just stores these stories up there in that remarkable elephant brain of his. Ever so often he takes one out, has a look at it, twists and turns it around, asks some questions -which he answers- and then he puts it back up there. I’m just glad I was born before the Internet came about (he actually did suggest that as a name too when my cousin got pregnant).

Yesterday, in the metro someone dropped teargas, we were all packed like sardines, and one by one we started sneezing, coughing, crying and you could see the fright in everyone’s eyes. A new attack? When we reached the next station we all ran out, there were people pushing, trying to save themselves – individual survival instinct wins over solidarity. But I guess we’re also taught this every time we sit in a plane and listen to the safety instructions: take care of your own safety before trying to help others. It gives us some sort of justification to think about ourselves first and not be struck by guilt afterwards.

It was rush hour in the metro and I had to wait for the two following trains in order to get on. I have no idea who dropped the teargas and even less why. Maybe it was just some stupid prank. It stirred up some heavy unease that night when going to bed, though. Thoughts were rushing through my mind at ferocious speed, I felt dizzy and almost in some sort of panic. I tried hugging a pillow, but didn’t work. Took out my phone, the light was aggressive and I put it back down. I tried programming a dream, a romantic dream, but the flushes of weird imageries came over me again. I opened my eyes and lay there for a while. Like when you’ve had a bit to drink and you lay down, worst thing you can do is close your eyes. I fixed them on my window and made squares out of everything I could, I used to do this as a child when feeling bored, now I do it to keep my mind together. The panic slowly disappeared. But now I couldn’t sleep. I went up and boiled water and filled up the half empty teapot I’d made earlier, found some old sweets that had expired in 2013, I figured that with all the sugar they should still be well preserved until at least 2023. If I had had someone to call, this would have been the moment to call him or her. Just to speak about anything, even about the weather, would have been fine. I am often very demanding when it comes to conversations being stimulating, but not at this moment, it would have just sufficed to hear someone’s voice, a familiar and warm one.

People often ask me, people from other places than Paris, if after the attacks we (Parisians) have changed our habits and how they have affected our lives. I’ve always found that question thoughtless and banal. I think with a little bit of imagination they could answer that question themselves. I often just answer that they scared us, some more severely than others, and that we probably all went through some sort of personal trauma when they happened. I recently learned that one of the books that surged after the attacks was Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast (in French, Paris est une fête). If our behaviour has changed I don’t know, and if it has I guess it has changed rather organically without a conscious link to the events.

As a child I loved it when my father brought out one of the items in his mind collection and shared it with me. I always pictured his mind as an endless library with ladders to reach up to the highest shelves, that’s where I imagined he stored the very best inventions. Despite my numerous attempts to request a specific story, he said it was not doable; he could only take out what was closest to him at that very moment. My father is getting older but his library keeps filling up, he still manages to bring out items I’ve never seen or heard about before and as I get older my admiration for his collection only grows. I called my father when I woke up and we chatted for about twenty minutes; I broke free from the bad mood I experienced the night before. My father was who pushed me to move to Paris. After the attacks he wanted me back. Both he and I knew that that wasn’t going to happen, but it felt nice that he tried.

The texts above are excerpts from the journal of Penny Black. I learned about Penny Black when I was sitting at a café one day. The couple next to me were art dealers. She was a chic woman with an Italian accent, I think, and he was a full-blooded American. They went well together, somehow. They were speaking about Penny Black, and my ears grew big like parabolic satellite dishes. I had never heard about her. As a writer I take everything I stumble upon in my everyday life to see if I can make any use of it in my writing. I didn’t want them to think I was eavesdropping, so I plugged in one headphone in my ear as if I was on the phone. Apparently they were struggling to get access to her archives. Penny Black was/is a conceptual artist who worked with trying to untangle what she saw as mysterious. She made her debut with a collection of anomalous stamps. She had been a peripatetic detective with the quest of finding un-rectangular stamps and seeks an answer as to why shapes that wouldn’t fit into a box would be rejected. All of her work has been thoroughly documented both in writing and pictures. Penny Black has recently gone missing. For months there had been circulating theories about abduction, suicide, Caribbean islands, but none had solved the mystery to her whereabouts. As I started my own research on Penny Black I was surprised about how I could have missed hearing about her. On Google I found endless articles about her and about her going missing. I grew increasingly interested in her life and saw a bestseller being born. I would call it The Anomalous Penny Black; it was a great title.

The more I learned, the more attached I felt. Since I didn’t yet know how to start the book or what to write about her, I started writing letters to her instead. Without any filter I poured myself out to her, I shared my latest findings about her with her. I had spoken to her father several times, I had even been over the English Channel to see him; he lived in Somerset. He was a sweet and somewhat introvert man.

One day he called me up saying he had felt Penny Black was definitely gone and if someone should get access to her life he felt it should be me. We met in her apartment in Paris at Rue des Martyrs later that same week. I was overwhelmed by her father giving me access not only to her very sought-after archives – but also to enter into her intimacy like that.

Her place was tidy but with items everywhere. If her father collected stuff only inside his mind, she extrapolated the affiliation of collecting into her apartment. It was a big apartment, surprisingly big. Her father explained the apartment was a legacy from his old aunt. To enter the apartment you passed by a guardian booth inside the hallway of the building, which felt funny. Like some sort of protocol was required. When leaving I took a picture of it, her father explained that the ambassador of Cuba used to live in the building. I wondered who was using it now since it was lit, but I didn’t ask.

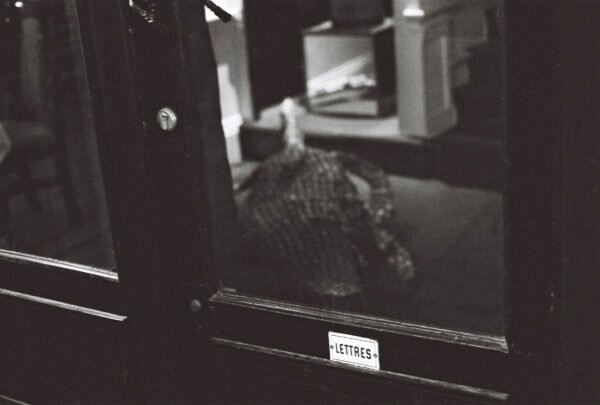

Inside the apartment, her father took his time to show me around. It had four rooms, a kitchen and a living room. One of the rooms had a glass door with a sign that said “Lettres” attached to it; inside, a big crocodile was lying on the floor; the door was locked. Her father told me he didn’t have the key to that room but that there was nothing to it except for what I could see from the outside.

Who wouldn’t feel intrigued by Penny Black? We went into a room that I guess served as her working space. There was a big curved desk from the twenties, or at least that would my untrained eye’s guess. Underneath the desk, there was a rather big wooden box, like the ones you can retrieve from market merchants when they are shutting down business every week. It was a messy box with several other boxes inside. Her father pulled it out and handed the lot to me. He told me he didn’t need it back but said I should be careful with how I used it. He hoped I didn’t have commercial ideas with this. I told him, besides writing a book someday, of course not.

We shared a coffee downstairs, I asked what he was going to do with the apartment, and he told me he would keep it like this. He said he was too old to be bothered about material things, and until someone said Penny Black was definitely gone he felt it was his obligation to keep a home for her to come back to one day – although he felt this was very unlikely to happen any time soon.

Back home I dug into the archives, read her journals, or more like her scrabbles of a journal; there were random pictures, pictures of people and places. There were also some poor attempts of self-portraits – I guess she never got these straight.

In one way I felt closer to her but I had hoped it would be clear to me by now how to start writing my upcoming bestseller. It wasn’t. So I continued to write my letters to her.

Then one day I decided to send them to her. I sent all of the letters I’d written to her address in Paris. I knew of course they’d just end up in her empty apartment, probably her father had a cleaning lady to keep the place in order – maybe she’d read them. In my despair to get started it felt as if I sent the letters it would trigger me to actually start writing for real – as if some sort of inspirational delivery would occur.

Two weeks later I received a letter, a handwritten one. I normally leave my post in the mailbox until I feel I really should attend to it, but seeing my name handwritten I tilted. Or actually it wasn’t the handwriting what caught my attention, but rather the stamp. It was an oval stamp, up on the right hand corner of the letter. I sort of instantly knew it was from Penny Black. I ran up to the apartment with the letter in my hand. I decided I needed something ceremonial to accompany me while opening the correspondence, so I poured myself a glass of Calvados and sat down in my armchair by the window to read it.

Dear Sacha,

You have access to a lot of me. But I have very little access to you.

I would be delighted if you were to share with me some of you.

Please send me some photos of your latest findings or observations.

Please, do not reveal anything to anyone, not even my father, about our correspondence.

The letter ended there. It wasn’t even signed and I hadn’t had time to take a sip of my Calvados. I felt strange. I was trying to put the puzzle together, wondering if I had been the subject of a big conspiracy. If the couple that day at the café had been planted there for my eavesdropping ears. If the father… I had endless thoughts and ideas on how it all ended up with me having a letter in my hands from the famous and disappeared Penny Black.

I decided I wouldn’t seek any answers straight away. I finished my Calvados in one big sip and went to bed. It was early but I felt exhausted. Next day, when I woke up, I knew exactly what I wanted to share with Penny Black.

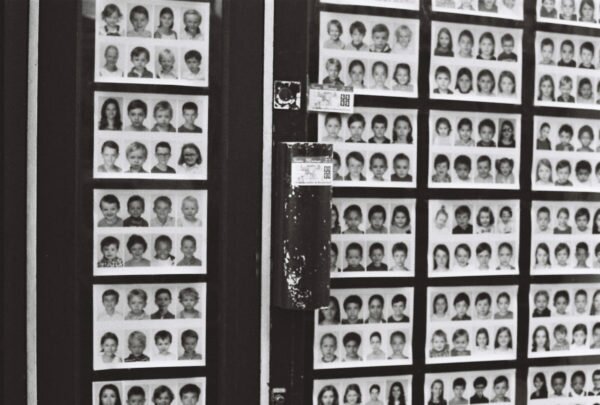

I sent her a photo of three Asian girls I’d seen in the metro earlier that week. I couldn’t figure out whether they were Chinese, Japanese or Korean. I asked for her opinion. Later that week I got a new letter from her, this time with a triangular stamp on the envelope. She said they were definitely Chinese: no Japanese would buy Kusmi tea in Paris. I laughed out lout – she was of course right. She sent me a picture of what seemed to be a door but filled up with children’s photos. She asked me what I thought it was.

We kept this type of correspondence for over two months. We collected moments and shared them with one another. It felt nice, and having Penny Black all to myself felt even nicer. I felt I couldn’t hide with Penny Black. She had questions to everything. She would, in her letters, twist and turn around her own ideas and then ask me what my hypothesis was. I often felt I didn’t actually have one. But having answered this once, I knew that that answer just wouldn’t do. The questions (that we would number with a special categorisation scheme) were a way for her to try to put into practice different concepts. We’d put things into different places only to see their relevance from a bigger picture. We also numbered our letters as we sometimes would send a new one before having received the replying one – it helped us keeping track of the conversations. None of us approached the subject of her going missing, or of where she was. I kept sending my letters to her address in Paris.

Her father called me once to ask me about my findings and how the writing was going. I responded that it was taking me some time to go through it all and to make sense of it. He didn’t seem surprised. I wondered whether he knew, he must, I was hoping so. It felt too cruel to have him believe his daughter was missing, probably dead.

Some two months later I woke up after a rough night with severe dreams. I had been tearing the eyes out of at least eight crocodiles that night. Jumping from one platform to another, crocodiles came at me trying to feast on my flesh. I had a special self-defence technique that consisted in ripping their eyes out. Not only did the eye came out but a whole piece of skin with it. I woke up exhausted from my acts of survival.

I went down to the market to buy some newly arrived blood oranges and bread. I stopped by the kiosk for some magazines and newspapers.

Back home, coffee in one hand and croissant in the other, I scammed a cover, and on one headline – bottom right of Télérama – I read “Le Retour: The Anomalous Penny Black”.

My heart started pounding. I went straight to the article. Penny Black was back. I could read there how Penny Black had felt she had nothing to hold on to, nothing explicit, tangible and that she was yearning for something her eyes could see and her fingers could stroke. She had felt the loss of inspiration and had decided to see the desert. She had gone from one place to another without any fixed itinerary but never with the intention of “vanishing”. But she had felt like going alone and telling no one: “People always have so many opinions they feel obliged to share, I do not always want or need these”, so she went without telling anyone.

She explained how strange it had been for her to discover that she was missing.

“I live alone, sure, and I travel – so people around me are accustomed to me not being around sometimes for weeks, sometimes for months. If I do not come home one night there will probably be no call to the police. This is just the way it is. Hemingway’s granddaughter, Margaux, was found several weeks after her overdose -all decomposed- in her own home. Margaux, like myself, was named after a precious idea from her parents, me after a stamp and Margaux after a wine, our destines are there – programmed as though they were in our genes. I grieved Margaux, and I still do. You can feel lonely everywhere. When we were under curfew after the attacks and alone, like I was and am, then you have nothing to hold on to, absolutely nothing. I would like to suffice for myself but I cannot. Facing solitude in a complete desolate landscape is much different from facing solitude in a crowded space, like a city. I came back because there was someone who had, without an ounce of fear, confided in me”.

Being gone had taken the upper hand of her, she explained, and as she was planning to maybe never return, she called her father. He hadn’t been too worried but had let her in on her missing status. He had also told her about me, “a banal writer with a quest to dig into your life” he said. But she had been intrigued. “My father sent me the letters and our correspondence commenced; it helped me get back into the world of the living”.

I felt my body slowly decomposing. The coffee was getting cold and my croissant was hardening up. The perspective of my bestseller was by now swept away. She had instructed her father and I had gotten access to her life. She had maintained her isolation act, but in Paris, by using the crocodile room which apparently had a hidden backside to the it, behind the mirror wall. This is where she had spent the following two months, corresponding with the writer, me. Simultaneously she’d written a book about herself starting in 1840. It was being released this week. The title was stolen: she used it for her book. I felt enraged and betrayed.

She revealed that her upcoming work would be about Paris. It would be a collaboration with the writer she had been corresponding with (over my dead body) and it would be a homage to both Ernest and Margaux, and she quoted, saying this was valid even for women, something Ernest Hemingway allegedly said to a friend in 1950:

“If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a movable feast.”

The following day I received a letter, with a real Penny Black stamp on it, inside a thick cutout carton paper with the following note:

Old Paris. New Paris. You will always be Paris of light. Ville Lumière. Forever returnable.

(Should we meet?)