Every day for seven days, Anna Senno walks between her home and the laboratory to develop one roll of photographs. 7 Days is a performance project reuniting photography and storytelling.

by Anna Senno

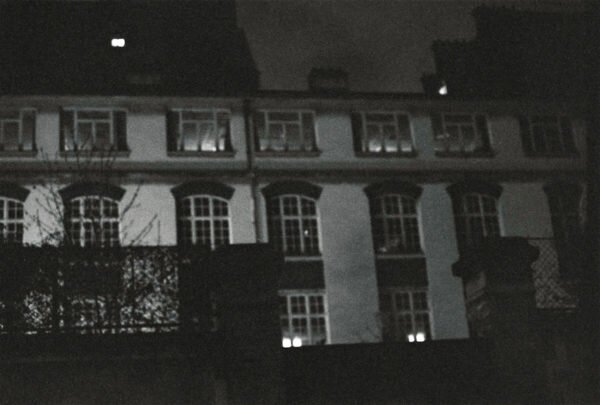

Paris, January 2017

A performance project

joining photography

and storytelling

Day 3

7 days,

Faculté

19 years old, stocky build, round face, thick curly dark brown hair, navy blue sweater with turtleneck, blue martingale overcoat, black shoes, carries a satchel under his arm.

Every day for seven days, Anna Senno walks between her home and the laboratory to develop one roll of photographs taken that day.

24 frames – she singles out 1-5, which become the basis for her storytelling. Fiction intertwined with reality: a fixed framework with no pre-established content. One roll and one story per day, for seven days, in pictures and words.

Camera: Canon FT QL – 1966-1972, 50mm 1:1.8

Film: Ilford B&W, 400 HP5

Laboratory: Processus, Paris

7 DAYS © Anna Senno. All images and text © 2017, Anna Senno. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used without prior written permission from the copyright holders.

The eleventh arrondissement in Paris is home to the most dazzling horror legend any Parisian has ever heard of. For a long time the story circulated around all of Paris and even found its way to the outskirts of the town. Often told at night by locals, around closing time in bistros and bars, its infamous horror would give nightmares even to those with dreamless sleep. Today only a few people are acquainted with it. Legend has it that a young man going under the name of Faculté would reappear every fifty years or so to face death. But before facing his inevitable death he would form a group of twenty-two plus himself. Carefully selected, the group would contain twenty people of foreign descent and three “locals”. A messenger would be assigned to the group. It would be a person with physical qualities that would allow him or her to operate without suspicion in society. All twenty-three would face a ruthless death. But the most horrendous death of all would be given to the seemingly innocent messenger of the group. He or she would be found beheaded with an axe…

We had just attended the latest rally against the Single Party Act that had been proposed earlier that week in the senate and were heading home. Solange agreed to share the bottle of Gamay that Sophar had just bought. None of us knew anything about this single act, but as Sophar had adopted the French “réac” demeanour -I guess to feel more French- we all accepted to join his cause. I am not sure he himself understood much of the different policies singled out or why he stood for or against. No, and I do not believe that was the point either, nor that important. What was important was to react, to take a stand -to act out-, to say that we are a community exercising our right to protest. Sophar, my husband, who had come to France from Georgia, was determined to become French. He would never admit it. He would say he didn’t believe in belonging anywhere, but he was more French than I’ll ever be. It was sweet; I enjoyed standing by him as he set out his life quests.

As we were about to enter our humble two-room apartment overlooking the Square de la Roquette, the concierge came running after us just before we reached the tiny elevator. When Sophar’s family came to visit they used it one by one. But we’d squeezed and were all able to fit inside it together. Sophia, our concierge, was sixty-something, a shy but sweet Bulgarian immigrant. She looked terrified and we had problems to understand what she was saying. She didn’t speak to us very often, or to anyone else for that matter. For several years, when we first arrived in the building, Sophar had tried to make friends with her. He’d drop by with a rare plant, or give her a croissant when he came back from the bakery in the mornings. She accepted his numerous gifts but never offered any conversation – to his great deception. I guess she intrigued him and by being so secretive he only got more persistent until he finally gave up. She took a deep breath, seeing we all stood like question marks in front of her. She then slowly articulated every word asking if we could join her into her apartment. The reason was that there was a man she could not be alone with, but that she couldn’t or wouldn’t send away either. We accepted to follow her, probably because this was the first time she had ever asked us anything over the last six years we had been living there.

None of us had ever been further into her apartment than the hallway. Her place was scarcely decorated but with objects that seemed to share an existential purpose with the place. We stepped inside the one-room home. Despite its small surface, she had been able to fit everything in there: a bed, a couch, a small round dining table and cupboards that covered the walls. Sophia sat down on the bed, Sophar and Solange around the table, and I remained standing. The man was sitting on the tiny couch. I immediately felt compassion for the young man on the couch – he seemed young but also grave, serious. There was a kind of energy in the room I had never experienced before and I wondered if Sophar and Solange felt it too. We all kept quiet, waiting for what was going to happen. Sophia leaned towards the young man and said he’d better welcome the group. He replied asking if she was sure these were the people. She nodded and said, “Yes I am sure”.

The young man welcomed us and thanked us for joining him and Sophia. He asked us some questions and seemed pleased to hear about us. He took interest in Solange, who like Sophar had come to Paris a decade ago or so. Solange was working for an association in Montreuil; she came from a wealthy family in Nairobi. Her family had sent her away when the violence against women had increasingly constrained her life. She had moved to London and then to Paris. We met at one of the conventions she organised against death penalty on behalf of her association. What had been happening in the last two years was a bit frightening: the death penalty seemed to be re-emerging in debates and political programmes. But let’s not get sidetracked, I must hurry to write this down before my important meeting.

The young man never told us his name that evening and I never heard Sophia call him by his name. He told us about the Single Party Act, we nodded and felt knowledgeable, since we had been to the rally. I felt proud of Sophar, who had brought us there. He gave us the picture of what was happening in society and he put the pieces of a puzzle together, one by one, and it all made sense. Our personal freedoms were being slowly removed; the Single Party Act would not rationalise and optimise efficiency as was expressed by its defenders, but rather lead to a totalitarian control of society. When I put my head on my pillow that same night I felt a wave of shame floating around inside my intestines. How could we live such ignorant lives? How could we not see what was happening around us, to people around us, did we not see or did we not want to see? Solange stayed with us that night and as we had morning coffee the day after we carefully started to inquire about how we all felt and what had happened the night before. We all felt that our lives had changed, that our existence had meant nothing up until that point and I would assume we all felt great excitement over the gain of meaning that the young man had provided us with.

We went down to Sophia’s, as agreed, around morning coffee to say that we wanted to take part in the endeavour but we had some questions I’d scrabbled down on a piece of paper. The first one was why we needed to be twenty-three. It was Sophia who answered: “Two is your divine life purpose and soul mission – Three is the Ascended Masters. Twenty-three is Duality, Charisma, Communication and Society. When we reach Twenty-three we’ll be handed the qualities to succeed in our mission”. Somehow this was all much less concrete and sense making but somehow it did make sense and it gave us a reason to believe this was out of our control. We felt chosen.

And so it all started. As our mission went on, our group slowly grew. There were people that were a part of our network but not members of the group. We grew over the following months and counted over a hundred people or so. In the beginning we worked mainly with communication – spreading the word. We were scouting members. I was the only French native and now had to find two more “locals” like myself to join the group – that was my mission. We needed three, I wasn’t sure why but I felt that it was us three who corresponded to the “Ascended Masters” and that made all the difference for me. Solange and Sophar worked closely and I could feel hints of jealousy from time to time. Our lives as we had known them slowly evaporated. I started to feel regret and I became more and more hesitant to the whole operation that had now been going on for over a year.

We would raid during the dark hours, meet with people none of us ever knew existed, we planned new attacks. We would infiltrate and recruit. We worked with scientists and carpenters, mechanics, programmers, technicians, you name it! Everything and everyone were of interest to the group. Our headquarters were for a long time in a tiny room in the attic of the closed-down library of the eleventh arrondissement. Cultural institutions, libraries, cinema theatres had all been faced with huge cutbacks and one by one were closing down and merging together to keep some activity running. The closed-down library was now hosting social events and workshops around artificial intelligence and DIY robotics. We’d keep the light on for ten minutes to let the network know we were operating so they could keep an eye on the neighbourhood.

The group had eighteen members now. It was becoming increasingly easy to gain support for the network as the Single Party Act had started to seriously take hold and intervene in people’s social lives. The world we were living in became black or white; the grey zones where we all had been hiding in were fading away. But understanding what was white and what was black had also become increasingly difficult.

Then, two things happened that changed everything for me. As I was about to recruit the third “local”, I was turned to the other side. I know this sounds like I am making excuses and as if I had no willpower to stand against the manipulation from the other side. And probably I would have been able to resist its temptation if it wasn’t for this other turn of events that occurred. Before being turned, and I think this was much due to the loss of connection I had felt for some time now with Sophar, we all gathered in the attic. Solange had been taking night shifts at the Hospital Saint Joseph to facilitate the meeting with the network, Sophar was out all night as well, I do not know where or what he was doing.

The young man, who we now called Faculté, announced that from now on we should communicate through our messenger; the game was getting more and more difficult to operate without being detected. As he presented the messenger, my stomach turned. In came a little boy, named Joe. “With Joe we risk very little exposure, and being a child he stands very little risk of being caught,” Faculté announced. Joe was a chubby kid with glasses, he looked Asian. Any communication of gathering or attack would be transmitted to Joe by leaving a note in the small metal box hanging in the courtyard of his school.

I didn’t go home after the meeting that night but went to meet the recruit I had earlier been in contact with to join the group – the one who came to turn me to the other side. I told her about what had just been said at the meeting, she nodded and said, “You should stay here tonight”. I did. I didn’t go back to the group ever again. One could say a full-fledged war was emerging out there. I kept inside, my former recruit provided me with what I needed and I started making costumes, theatrical costumes, puppets, covering furniture with new fabrics. I could not stop. I dreamt about Sophar every night. The witch-hunt had started, anyone not local was a subject of inquiry. Suspicion reigned but I was safe. I will hurry up now, we need to leave soon, very soon.

We were invited to the hearing of the group. I guess I should have felt privileged, only the biggest VIPs were invited to attend, – movie stars, VR creators, The Selfie-taker of the year, even the president would be there. They’d arrested them all, all of the Twenty-three members, I guess I was easily replaced. I felt disgust, disgust with myself. I had chosen the easy side. As I sat in the hearing watching Sophar’s back, that I knew so well, I wanted to throw myself over him, hold him, just hold him.

This was ten years ago. We all know what happened afterwards. I somehow never got charged with turning sides or being an infiltrator. The guilt I bear on my shoulders is my rightful burden to carry with me to the grave. I moved to Rue Marcadet in the 18th arrondissement when war was over. Opened my small atelier, continuing to make costumes and other meaningless work. After the trial, people would all put lit hands made in gypsum in their windows in support of Faculté. I didn’t. Sophar was gone. They were all gone. All but Joe had been brought to execution. They’d been taken to the newly inaugurated public square for this. I didn’t attend. I sometimes go there nowadays, though. Ironically, it is just around the corner from our former apartment. A small park we could spot from our bathroom window if we stood on the toilet seat, something we used to do every month to see the full moon. I guess I knew the fate of little Joe when I saw him and my stomach turning was a premonition of some sort. They’d waited a couple of months to announce his sentence; actually, they never did announce it, they just did it. He was taken to the city of The Hague where his head was cut off with an axe.

The gruesomeness of what happened is beyond me. I need to leave now, I have decided today is the day. All arrangements have been made, I will pay my dues now and lay down to rest, I have regained my freedoms as a human being but freedom is nothing when you bear the guilt of not having paid for it yourself.

.

Epilogue

.

Légion

Si j’ai le droit de dire en français aujourd’hui

Ma peine et mon espoir, ma colère et ma joie

Si rien ne s’est voilé définitivement

De notre rêve immense et de notre sagesse

C’est que des étrangers comme on les nomme encore

Croyaient à la justice ici bas et concrète

Ils avaient dans leur sang le sang de leurs semblables

Ces étrangers savaient quelle était leur patrie

La liberté d’un peuple oriente tous les peuples

Un innocent aux fers enchaîne tous les hommes

Et qui se refuse à son coeur sait sa loi

Il faut vaincre le gouffre et vaincre la vermine

Ces étrangers d’ici qui choisirent le feu

Leurs portraits sur les murs sont vivants pour toujours

Un soleil de mémoire éclaire leur beauté

Ils ont tué pour vivre ils ont crié vengeance

Leur vie tuait la mort au coeur d’un miroir fixe

Le seul vœu de justice a pour écho la vie

Et lorsqu’on n’entendra que cette voix sur terre

Lorsqu’on ne tuera plus ils seront bien vengés.

Et ce sera justice.

Paul Éluard

Poem to the Manouchian Group,

written in 1949, published in 1950.