Through a GIF by Jiri Trnka, Alexandre Serrano defends traditional animation, folklore and roots.

AND

By

Alexandre

Serrano

KITTENS

Elizabeth L. Eisenstein says in The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe that the popularisation of printing wasn’t used primarily for the dissemination of the great texts of European humanism, the promotion of science, the spreading of the encyclopaedic spirit or the circulation of any other high culture outpours. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, what really abounded under the press were erotic and pastoral literature; chivalric romance; peasant almanacs filled with riddles, sayings and tales; low-class political pamphlets, and, above all, an extraordinary variety of missals, lives of saints, couplets, speeches and bibles. Should we forget this fact, we would end up with a very biased view of the society of those times and its way of producing discourse and meaning.

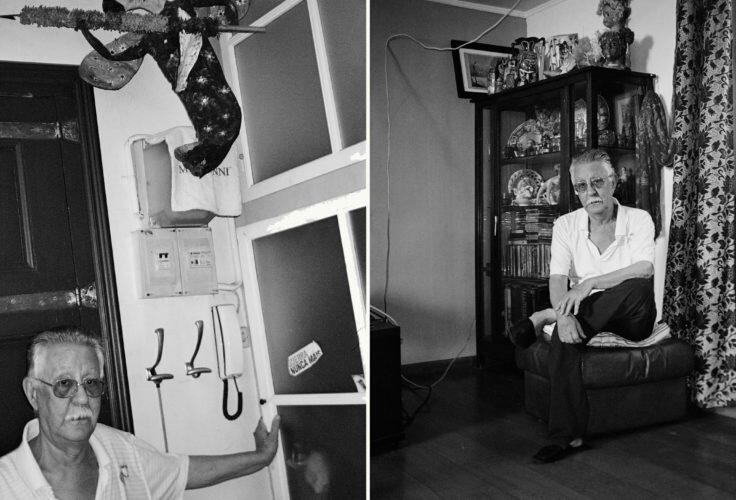

This publishing house understood from the beginning the fact that animated images could illustrate us, as well as these times we have to live. Fragmented, anonymous or of unclear authorship, offsprings of recycling and virality, thus are today’s works. And as such, a relevant indicator of the humour, references, expectations and demons of those inhabiting the world in which they’re created. But their acuteness would be questioned if we only referred to their most excellent and original manifestations, to anything standing out in the midst of the digital tip. Because most of what circulates on the net appeals to basic instincts and proceeds with a direct language, satisfies the desires of the lower belly or rejoices in sentimentalism and frippery. It all consists in, to sum it up, either tits or kittens. Which, as Eisenstein tells us, it’s more or less what popular communication has been all about since the beginning.

This Weekly GIF image has the originality of articulating both elements while at the same time mocking them a little. There’s a cute kitten and a generous cleavage, but their disposition and use are what create the joke. It isn’t a heavy satire, more a perverse note. A cartoon linked to a certain classic black humour comic strip, devoted to acid and clever social critique more than as a direct diatribe. It makes fun of the vulgarity of common taste without ceasing to base its contents on it. It takes the two most overused resources in the net and subverts them with a graceful magician gesture. And it’s possible that standing in front of the mirror, with a light irony and relativizing the gravity of the matter, might be more lucid than the ominous millenarianism telling us about cyber cultural catastrophes, the final degradation of sensibility and the dawn of the illustrated world that the Internet has brought about. Or did you think there was a time when Kepler’s treatises and Linneo’s botanicals were passed on from hand to hand?