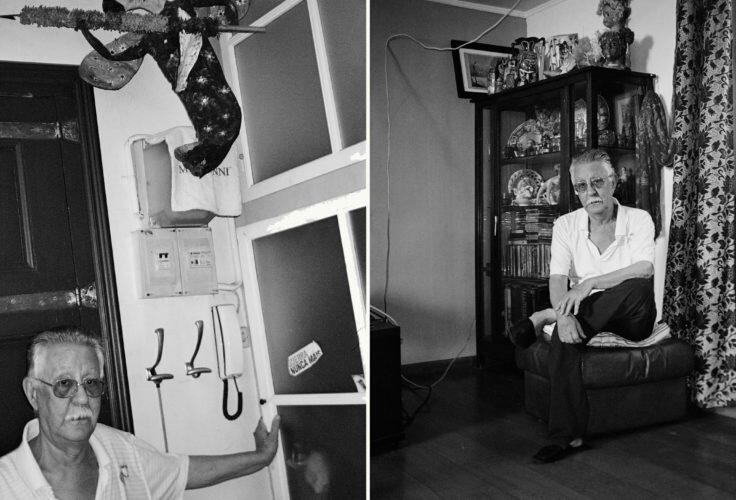

Thirty years later, Óscar del Pozo sees again La ley del deseo. From the first video club rental to the current Almodóvar cycle at the Filmoteca things have changed a great deal.

Sun and Steel

Yukio Mishima

A freak

Mishima story

for all

gym freaks

By Óscar del Pozo

He spent the last fifteen years of his life working out at the gym. When he felt he was muscly enough, he started taking snapshots of himself with no T-shirt on, in pure selfie-Instagram style (in one of them he posed as Saint Sebastian, with arrows and all). And he despised aged writers, to whom he devoted improprieties such as “the face of the intellectual whose youth is history horrifies me: it’s ugly and uncivil”. Cristiano Ronaldo? Zac Efron? Sergio Ramos? Chris Hemsworth? Cold, cold: we’re talking about Yukio Mishima, prolific writer, bigger than life character and pioneer of a lifestyle that almost no one in their right mind would have wanted to follow in mid last century. Forty-six years after his premature death, though, what used to be an exception is today the norm. So maybe if we look in Mishima’s mirror we might see our own reflection.

“Muscles have become virtually superfluous for modern day life. Even though they are still vital to the human body, they are obviously useless from a practical point of view, and a notable musculature is as unnecessary as classical education for most practical men. Muscles have ended up becoming something like ancient Greek”. This is the way in which the Japanese writer wrote about it in his essay Sun and Steel: corpulence seemed as unnecessary as a dead language. It’s 1968 and Yukio explains why, despite this, he has become a pioneer of our present day vigorectics, obsessed with gym work-out routines: “In order to achieve a romantically noble death, a magnificent physique and a sculptural musculature are essential. Any confrontation between weak, flabby flesh and death seem ridiculously inappropriate”. Aesthetics above everything else: two years later, Mishima commits suicide by stabbing himself on the stomach with a sword (in a savage ritual known as seppuku, which concluded with his beheading), but at this point he’s still not ready for it because his six pack is not developed. Decades afterwards, the many Adonis of the world will find a similar problem before the imminence of their holidays in Ibiza or Barcelona: they will have to workout hard to be able to take their T-shirts off in Ushuaïa or Circuit.

What the author of The Temple of the Golden Pavilion hadn’t imagined is that muscles would cease to be of use in order to work in the fields or at factories (labour work was moving towards the office), but would end up being a criterion in the narcissistic competence we live in more or less since the pill and condoms started being commercialised, Studio 54 opened its doors and Saturday Night Fever was premiered. In our erotic-advertising society, which Mishima never got to know, sex has become ultracompetitive and muscle size one of the many evaluation criteria. Back then, their goal was very different: Yukio wanted to stop being the typical man of letters, sedentary and solitary, who only aspires to hyper-atrophy the mind. “When I see myself in the mirror, I despise myself thinking: ‘Look at this pale, sick-looking guy that only talks about literature’. I’ve become a strange being, distanced from everyone and everything, who only cares about writing”, he confessed in an early letter to a friend.

The yearning of the creator of Confessions of a Mask was to become a man of action. He thought with reason that the cynicism with which intellectuals judge a combative spirit has to do with their feeling of physical inferiority. Mishima was convinced that if he improved his physique, his personality and literary style would improve as well. “Weak emotions reminded me of flabby muscles, sentimentalism of a flaccid stomach and excessive susceptibility of a white and too sensitive skin”, he wrote in Sun and Steel. His goal became a titanic battle against his own nature: only with his effort, without the help of any creatine or powder protein or, least of all, anabolic steroids, he stopped being a weak and sickly boy who failed his physical education tests and became a hottie with “tanned and shiny skin and powerful and delicately toned muscles”, according to his own definition.

Once he achieved his goal, at forty-five, all Mishima had left to do was waiting for his own physical decadence. But that perspective horrified him. “No matter how long and intense the training, our body, deep down, is progressing little by little towards decadence”. In one of the interviews included in a book of recent publication in Spain, Últimas palabras de Yukio Mishima [Yukio Mishima’s Last Words] he said he didn’t want to resign: “To live doing nothing, slowly growing old, is an agony, it’s like tearing up our own bodies. All this has taken me to think that, as the artist I am, I should make a decision”. Those words were a warning of his ritualistic suicide, which took place in 1970. Then, nobody understood him. In Japan, a society that respects and reveres its elderly citizens, Mishima was looked at as a madman. But in our contemporary society, so narcissistic and obsessed with youth, it’s easier to understand why he couldn’t bare the perspective of his own decline.

Soon after his death, the entertaining industry started venerating youth, and still does so nowadays. Very soon, gyms became popular, first in some big European and North-American cities and later on everywhere else. And teenage years stopped being a phase to become a state in which many of us will live until the end, while we see our bodies deteriorating little by little. Today, we’re all terrified of growing old. People get obsessed by their age too soon and all they do from then on is getting worse. That’s why, seen today, Mishima’s suicide doesn’t seem only an insane thing, but a sublime poetic act. What the writer did was assuming the brutality of living under the parameters of youth, strength and beauty, and responding in an equally brutal form.