Spirals give Alexandre Serrano the chills. And if they’re in GIF format, even more so. Here he lets himself fall into the whole.

THE PHANTOM

•

ARSENAL

BY ALEXANDRE

SERRANO

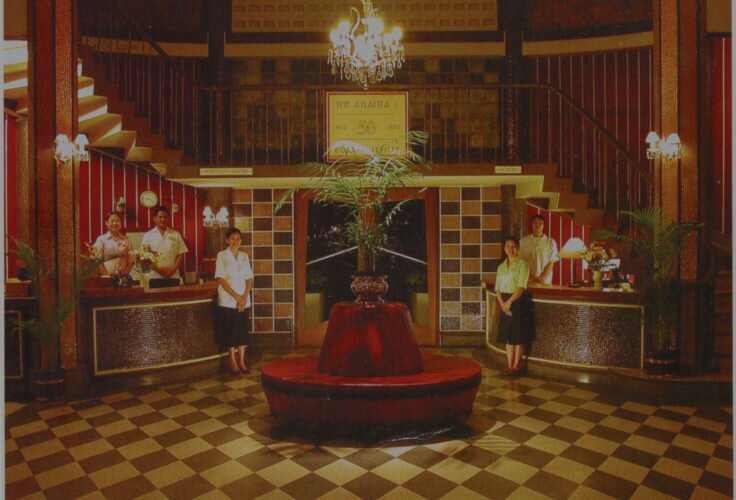

I live in the company of spirits and their presence feels comfortable and dear. They populate every corner of my house, hang from some of its walls and rest on the bookshelves. They emerge from the collection of old ethnographic photographs I’ve been gathering without any other method than astonishment, the permanent wonder of discovering how diverse and precious the world they came from was, how definitive its shapes.

It isn’t about, or at least not only, an aesthetic and nostalgic cult. These snapshots connect me, firstly, with a concrete ethic and attitude, that of the men that took them, frequently having to stand difficulties, incomprehension and headaches. I think, for instance, of one of the heroes in my gallery: Edward Sheriff Curtis.

Curtis had a certain well-off status thanks to his Seattle studio, where he took portraits of the bourgeoisie from that north-Pacific city. But in 1899 he had an epiphany: he came into contact with Indian cultures and perceived that they had begun to withdraw and assimilate. From that moment on, he decided, with mad determination, to shoot them anywhere he could in the US and Canada. The results were more than forty thousand photographs, as well as the twenty volumes of one of the great documentary works of all times: The North American Indian. He lost wife and fame along the way, had to take many odd jobs to earn a living and died forgotten by the public and specialist which recriminated him his lack of formal training. In exchange, he let us something irreplaceable.

Hi accomplishment might only be comparable to that of Albert Kahn, Alsatian banker and philanthropist who invested all his immense resources in another titanic oeuvre: Les Archives de la Planète. Between 1909 and 1931, his agents went around the world to capture up to seventy-two thousand autochromes, with a special interest for those anthropological manifestations threatened by the speed of modernity, changes in manners or wars and their migrations, a legacy that had fallen into an incomprehensible oblivion until its contemporary re-discovery.

The copies of images taken by Kahn and Curtis coexist under my roof with more works by other ethnography and photojournalism pioneers, like the ones that Felice Beato brought from trips to the Far East, Désiré Charney took in Madagascar, Martin Gusinde took in Tierra del Fuego or . But also with many by unknown or almost anonymous portraitists that didn’t so much look for what was exotic or menaced, but saved instances of their immediate surroundings without suspecting that their warm everyday life was about to become obsolete very soon.

If I find them so magnetic it’s because they all teach me about a concrete form of resistance. Even in those cases in which photography reveals a colonial, patronising and out of context outlook, I can read in the somewhat hieratical stance of its subjects a fierce and not at all faked dignity, that of communities that maintain a determined singularity and autonomy, of individuals whose roots and faithfulness to something that transcends them embody the sense of their existence, and also of ours: they retrieve something that we’ve lost, but still belongs to us.

There are times when living in the mist of this parade of shadows makes me shiver a little bit. It’s as if they look back at me and, in fact, as if they look even beyond me towards a photograph which includes me, a piece of amber in which it’s me who’s crystalized: the image of a collector worried about the subtleties that in an imprecise moment of the future will have become too an extinct rarity. It’s the powerful thing about invocating a memento mori that Roland Barthes recognised as one of the most excruciating of the eighth art.

However, most of the time they have a much more encouraging effect that is equally created by the phantom nature of the photographic act. Because all those images are and are not at the same time: what we see in them has ceased to exist and, at the same time, it is there, intact and powerful. They show us how the past persists, survives in secret and larval forms, keeps portals open so that we can communicate through them, and reminds us that there can be lives far are more authentic and less biased than the ones we might have surrendered to. And thus, their spectral rebellion challenges the tyranny of the present, the suffocating nightmare implying that their grotesque silhouettes are our only horizon.