The fatigue of language; the exhaustion of images; the weariness of bodies: Carlos Losilla researches these symptoms in books, essays and films.

SOME NOTES

ON THE FASCINATION OF CREPUSCULAR ART

By Carlos Losilla

Joel McCrea looks to the horizon before he passes away in an overwhelming shot, which shows him as he lays dying, on the ground, with the mountains he loved so much at the back of the frame. His ex friend Randolph Scott has wounded him during a strange confrontation that took place at that deserted spot… Do you need any more clues? No, I think you have guessed it already: indeed, I’m talking about Ride the High Country, Sam Peckinpah’s second feature film, probably the “crepuscular” western (i.e. portraying the death of the Old West) par excellence, the great elegy for a West that no longer exists, not even for those two old gun men who wander around lost in an ever-changing era. Eleven years later, in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Peckinpah himself will shoot outlaw Kris Kristofferson talking to sheriff James Coburn, also his best friend. Garrett: “Times are changing, Billy”. Billy: “Times maybe. Not me.” We could go on, since in fact Peckinpah always shot the same film, narrating the same discourse over and over: the need to be faithful to your own values, no matter how much the external world evolved in a different direction. And not only him, also more veteran directors such as George Cukor –from Love among the Ruins to Rich and Famous–, Howard Hawks –from Man’s Favorite Sport? to Rio Lobo–, Vincente Minnelli –from The Sandpiper to A Matter of Time– or Billy Wilder –from The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes to Fedora–, rummaged through the classics for the last time in the sixties and seventies, with the purpose of giving the end of their careers a melancholic touch.

I remember those times while I listen to music from a very different age, the one we find ourselves in. Fallen Angels, Bob Dylan’s last album, goes back to the classical settings of his previous record, Shadows in the Night, to go on re-visiting jazzy and melodic standards like the ones Frank Sinatra used to sing, among others. Everything happens in a whisper, with some guitars and Dylan’s dull intonation telling us that everything has an ending, and that even he is getting close to his. On the contrary, Stranger to Stranger, the return of Paul Simon to the studio after five years of silence, researches the memories of the composer to offer a series of songs that could well have been featured in any of his former albums but now, song after song, treated with an atmospheric sound that leaves them hanging in a time that is diluting little by little. It could seem that Dylan and Simon use opposite strategies, but deep down they’re not so far apart: while the former maliciously confesses, in his usual oblique and elliptic style, that he has always been making this kind of music, really, that these are his origins, the latter tells us, to our ear, that he has never left the place he started from. Faithfulness, values, tradition. Sometimes, “crepuscular” art can be a bit conservative, but it’s also a creative experience fusing two worlds, two ages, with the goal of advancing in a third space that is taking shape little by little. A dialectic method, indeed, that would surprise even Eisenstein himself.

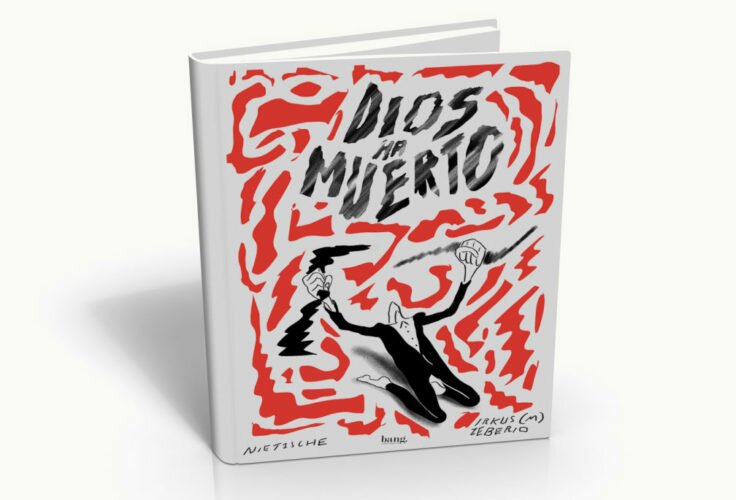

ILLUSTRATION BY LUIS MAZÓN

In other words, what many defendants of the “classics” that grasp “crepuscular” works as if they were the only modern stuff they could bear don’t get is that this melancholic turn shows no nostalgia whatsoever. It’s not about observing Peckinpah or Dylan –who, by the way, already met precisely at Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid– as if they were the last heroes of a soon-to-be-extinct lineage, but to see them, each one in their own time, as the first instances of a new aesthetic. When Cukor and Minnelli, Wilder and Hawks, made their last films, they coincided with many more or less young filmmakers that were creating what would be called ‘New Hollywood’, no doubt one of the basic seeds of contemporary film: Coppola, Scorsese, Altman, Ashby, Pakula and many others who took as their base the twilight of certain genres with the purpose of deconstructing them and preparing them for a truly experimental era that would reach its peak with Fassbinder, Garrel, Kiarostami or Tsai Ming-liang. When Dylan and Simon go back in order to take a step forward, they are conscious that there they have Sufjan Stevens, Julia Holter or even Morrissey to keep on researching new modulations of the same musical tradition. When Peter Handke seems to be starting to bid farewell with Storm Still –some title, no doubt–, John Banville’s maturity in The Blue Guitar shows us that novel fiction is starting to think about itself in other not so far-away territories. All in all, when Rembrandt painted his self-portrait at 63, in 1669, he probably knew he was opening the experience of pictorial image to new paths that would culminate in the abstraction already pointed at in many fragments of that painting so admired by John Berger…

The times in which certain art forms begin their crisis, crepuscular times, are always so for a certain norm that rejects at the same time a new one that is just emerging. Well, it’s at that suspended moment, when things stop being one way to start being a different way that past and future cross each other in what is considered a privileged time. No nostalgia, thus. No Bogart-and-Marilyn and there’s-no-movies-like-in-the-old-days. No no-one-will-tell-stories-like-Shakespeare –the crepuscular playwright par excellence, we might add–, nor-to-sing-them-like-Dylan. In fact, we’re always living a crepuscular time or another. Or weren’t classic Hollywood films “crepuscular” from the beginning, as the last incarnation of realist novels and plays? Aren’t Pedro Costa and James Gray, Arnaud Desplechin and Hong Sang-soo crepuscular filmmakers, in the sense that they take a certain inheritance of that same classic film to the utmost limits? Each move forward is also a step back, it cannot exist without that movement that makes it go back for a moment to gather the ruins from the past, soon reformulated as avant-garde. Time moves like waves transforming themselves on the shore, at the beginning of a summer that will too become crepuscular.

Rembrandt, Self-portrait at the Age of 63, detalle