What do we talk about when we talk about “crepuscular works”? Carlos Losilla distrusts this label, which is applied to films, records and books. Illustration by Luis Mazón.

Purism

or ambiguity.

by Carlos Losilla

1.

I re-read Sur un art ignoré, a text about the filmic mis-en-scène that Michel Mourlet published on Cahiers du Cinéma in 1959. Turned into a kind of unknown classic, this involuntary manifesto is important for different reasons, the least of all not being its condition as limit point. Since the formalist appreciations of André Bazin and his disciples at the Cahiers, displayed earlier on at the same period, were now surpassed by something much more extreme: the mis-en-scène wasn’t only a question to do with camera and motion, of time and space, actor and set, but above all a “fascination”, a rapture, a ecstasy, in the end something very close to the outburst that years later Iván Zulueta tried to define. And only directors such as Raoul Walsh, Otto Preminger, Fritz Lang, Joseph Losey, Hugo Fregonese or Vittorio Cottafavi were capable of achieving that something that only films could show.

But the most important thing in Mourlet’s text (that you can read in Spanish on magazine ) is not so much what it includes as what it excludes, particularly when it comes to North-American films of the time. The Cahiers critics had already ex-comulgated directors such as Fred Zinnemann, Elia Kazan, George Stevens, Stanley Kramer or even William Wyler for what they considered their “sensationalism”, for a direction that underlined more than showed, for certain psychological and ideological structures that ended up becoming more important that the essential true of the mis-en-scène itself. Mourlet, on his part, went even beyond and defames with his text some of the sacred cows for the Cahiers: Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Jean Renoir, Roberto Rossellini, or Robert Bresson, among the most representative, were for him no more than petty illusionists, mediocre directors and indifferent to the capturing of what really defines film as such, that is, “light, space, time, the insistent presence of objects, the shiny sweat, the thickness of hair, the elegance of a gesture, the abyss of a look,” in Mourlet’s own words.

The more purity a certain vision of film demands, thus, the more exclusive it becomes, and fewer directors can enter its pantheon. Should we convene that any theory is purist from the moment in which it formulates “behaviour norms” for the art in question, and which entail an absolute rejection, an expulsion from paradise, for those not abiding by them? In any case, it all becomes more and more ambiguous to me. On the one hand, that purism becomes a repression, and even provokes that certain histories of the cinema still look with contempt at some films that today would deserve a completely different kind of consideration: maybe High Noon and From Here to Eternity aren’t exactly brilliant, but that doesn’t mean that Zinnemann never shot any films that we should definitely watch today, from Act of Violence to Teresa. On the other, what would films be without such a demanding high level of thoroughness? Would it end up becoming an anything goes? Where should we set the limits?

Illustration by Luis Mazón

2.

I remember that the emergence of punk rock in the UK came with the violent condemn of the dominant sound of the times. The leaders of the Sex Pistols and The Clash rushed to criticise bands such as Genesis, Pink Floyd or Yes, seen as dinosaurs about to become extinguished, representatives of baroque, old-fashioned music that had distorted the original virtues of pop and rock and roll. In the same way in which François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard rebelled against “dad’s films”, i.e. French academic cinema from the post-war period, Johnny Rotten and the Ramones were also ready to kill their fathers, in which they didn’t see themselves.

Again, the impression is the same. The punk and neo-pop gale took away all the symphonic fanfare, but didn’t it also leave some corpses along the way that maybe didn’t deserve to have become so? Should we listen to Genesis’ complete discography, for instance, the binge might be fatal, but do not albums such as Selling England by the Pound o The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway possess a million of fertile ideas, of visionary findings, albeit partial, without which many of the subsequent feats would have been impossible?

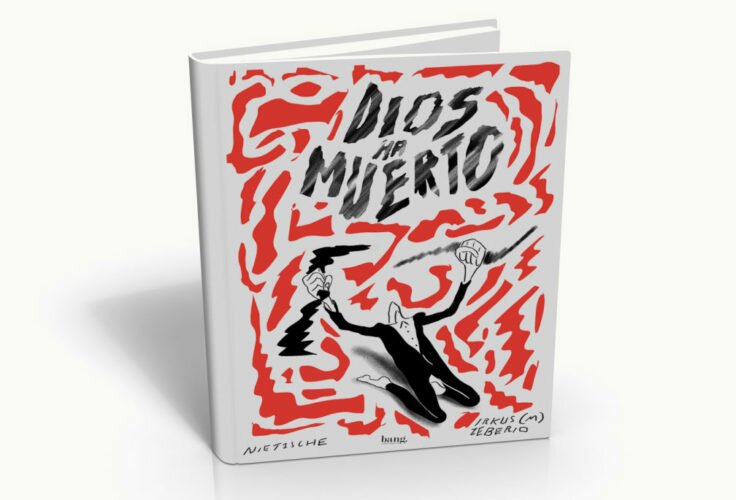

The history of popular music, however, has been constructed in the last few years without taking these kinds of details into consideration. And progressive rock has been almost completely locked in a dark room for the same reason that most cinephiles passionately love Fritz Lang and despise Jean Negulesco with a certain degree of contempt. The same reasons, too, for which book fans who consider themselves lovers of literature in its purest state preserve in their bookshelves volumes by Marcel Schwob and Samuel Beckett, Robert Walser and Hugo von Hoffmannsthal. What the latter always argue is quite interesting: literature is not only to do with stories… Maybe it has to do with the “fascination” that Mourlet was talking about?

3.

That mystique of purity, thus, is present in any art manifestations with a never-ending thirst for destruction and persistent politics of forgotten and despised objects. I insist: where is the limit that might, at the same time, preserve a certain aesthetic so as not to become a victim of the dictatorship of today, but neither to given past hindrances, but which enables to build a more eclectic canon, with less prejudices, but not meaning improvised or arbitrary either? The story, we were saying; the story above pure form. It’s funny that Stanley Kramer, Yes or Somerset Maughan share a taste for that “story” that little by little becomes a continuous evolution and mixture of forms, a never-ending arabesque, a melody disentangling itself. Saying things, narrating events, describing in detail a musical line unfolding in time.

Both Shane and The Big Country, westerns by George Stevens and William Wyler respectively, tend to that overwhelming display of melodies and events. No, they don’t hold Hawks’ purity of form, or Hitchcock’s deliberate abstraction. Neither do they present, as Mourlet would have wanted, Preminger’s sparseness or Walsh’s captivating rhythm. But from their stories emerges, not a different conception of film, but many complementary proposals that could modify our precepts, what we think would be one way and not another and -why not?- might be taking us to occupying positions a bit too locked within themselves. Film, music, literature do not only evolve in the present, but also in the image we make of their past and which sometimes becomes fixed for too long. C’mon, confess, how long it’s been since the last time you watched Kramer’s Judgement at Nuremberg, that film in which the story is suddenly interrupted by the shining appearance of Montgomey Clift’s already disfigured face as a kind of spectral irruption? There’s nothing pure in that film and, however, it’s so beautiful! Even if it’s just at certain moments…