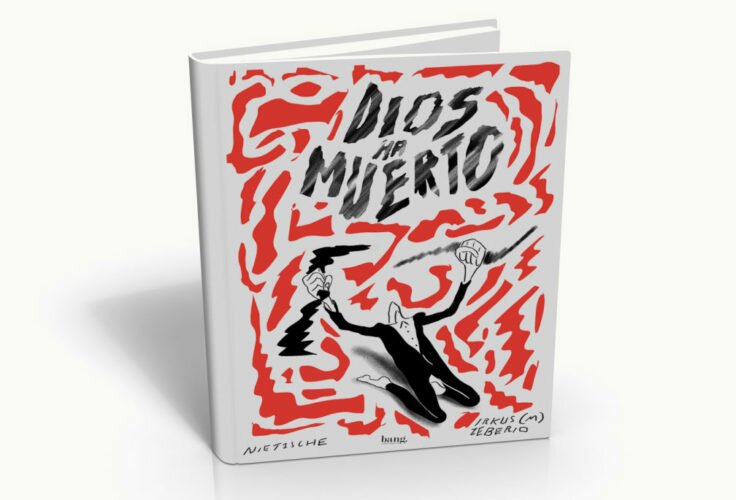

Scott Fitzgerald used to say, “Good writing is like swimming under water and holding your breath.” Good reading is a similar feeling, according to Iban Petit.

SPECIAL

READING AND AUGUST

Text by Miqui Otero.

DUMB

IF YOU READ IT

(FAST)

Illustrations by Josep Román, Affaire.

2.

Reading time for this article is 5’. Or maybe 7’… Or was it 15’? It all depends on the time you’d like to devote to understanding and/or enjoying this text by Miqui Otero. Because reading isn’t an activity one can do chronometer in hand. As Woody Allen’s popular joke used to say: “I took a speed-reading course and read War and Peace in twenty minutes. It involves Russia.”

“The Text is very much a score of this new kind: it asks of the reader a practical collaboration. Which is an important change, for who executes the work? The reduction of reading to a consumption is clearly responsible for the ‘boredom’ experienced by many in the face of the modern (‘unreadable’) text,” Roland Barthes, in “From Work to Text”, taken from The Rustle of Language.

“DATA, MORE DATA!,” JOHNNY 5, IN SHORT CIRCUIT.

Poor Henry Bemis, poor specks! His boss doesn’t allow him to open a book when he’s at work, when he covertly tries to read David Copperfield crouched behind the window of the bank he works at, and his wife leaves him and challenges him to read a poem and spits back a mocking laugh. Luckily there’s some kind of nuclear disaster and he’s left alone in the world. He roams around a devastated planet until he envisions a ruined library. Among the mountains of rubble, he discovers a bunch of books, literature classics. He cries out of pure joy and mumbles: “Time, time enough at last.” He has eternity in front of him to read without anybody bothering him. Then he stands up to grab a copy and his spectacles fall down on the floor and the glass breaks and he, who can’t see beyond his own nose, knows, at this precise moment, that he has a long and lonely life in front of him, and, besides, with no books.

Well, stuff it! Every time I watch this legendary Twilight Zone episode, entitled Time Enough at Last, I think the same: you should have read before!

If you don’t have time to read, probably you don’t like reading. People who don’t read have more excuses at hand than a football team in their worst season ever: the weather, friends, a bit of sinusitis, stiffness of the index finger they would turn pages with, a tropical fever, the existence of mobile phones. Then, what they do after that is saying how much they would read should they have the time. They devote so much time to that activity itself that they could probably read Gravity’s Rainbow should they devote to reading the time they use to moan. I imagine them cheering themselves every time they finish a book, like those Easter dictators who self-cheered themselves after their speeches, or like those babies that applaud after eating a yoghurt.

The favourite character of these non-readers would be, probably, Johnny 5 from Short Circuit. That wayward robot able to read a whole encyclopaedia in a minute and a half, who screams: “Data! More data!” They would love to be Johnny 5, to be able to read super fast and lots of books and be able to say the have read them. But why are they in a hurry? The US army is not chasing them to send them to a scrapyard in Seseña!

1.

2.

I’ve run eight kilometres, I’ve burnt thirty-five calories, I’ve read eleven pages of Veronika Decides to Die (And I’m still alive!).

Some people see reading as a kind of additional vitamin supplement with which to reinforce their personality, as a sort of Popeye spinach can with which to gain intellectual muscle to be shown off in some situations. Maybe that’s why they post the pages they’ve read on social networks in the same way that runners post their kilometres to Nike +. They want to: a) show us their records; b) do it fast. Maybe that’s why some of them also look for miracle solutions to read more in less time. They aspire to read everything, I assume, when in fact the more you read, the less you think you’ve read. If some people that want to lose weight but “have no time to go to the gym” use fat-reducing creams (“Somatoline 10, lose weight while you sleep”) or electric girdles that in theory leave your stomach flat as a pancake, some readers with no time to read look for similar inventions on the Internet.

Many of the web sites or apps that promise you to be able to read more in less time have names that remind me of protein products for people with bigorexia, energy drinks, Shop TV products or ultraviolent videogames: Jetz, Spritz, Speed Reading Trainer, Readline. And they inspire me exactly the same amount of confidence.

Kindle tells you, for instance, how much time you have left to finish your book. Knowing, for example, that El tiempo entre costuras, read at three hundred words per minute, will mean devoting to it eight hours of your existence produces the same terror as counting how many fags (and money) you smoke in one New Year’s Eve. However, knowing that you can read a Harry Potter novel in the time a football match lasts makes you really sad, because you’d prefer to live forever on a quidditch match. Reading time (and time alone) doesn’t exist: a minute during an earthquake in Chile can feel longer than a whole month of August in the Caribbean. But the thing is that now we have apps and web sites such as howlongtoreadthis that calculate how much you will take to read a book on paper, with a database of around twelve million works. It’s useless to argue before these reading-fitness fiends that to me the eighty pages written by Karl Ove Knausgård explaining how he cleaned his recently deceased father’s garage seemed like a short breath, or that the three books Tristram Shady takes to appear on the novel that bears his name were for me like two minutes. But adipose intellectuals want to quantify everything. Some of these apps, for instance, offer you the possibility of reading without moving your eyes. Words circulate at an adjustable speed through a kind of viewfinder so that the reader can accelerate and not lose those precious seconds he inverted in reading the page from left to right and right to left (or up to down).

These kinds of inventions powerfully remind me of a revolutionary invention promised by inventor-prophet Dean Kamen. He said that mammals first swam, then crawled, and then proudly stood up to walk on two legs… His invention, he argued, would anticipate the following step on the evolution of Earth civilisation. Shocked faces when, in 2001, he uncovered the mystery by removing the sheet hiding his device on the day of its launch: a Segway. He showed the press a Segway. A fucking Segway! Those electric super expensive two-wheeled tricycles only used by Scandinavian policemen and tourists sporting bum bags. That is, exactly, what I think about those new reading methods.

We’ve been measuring time for around six thousand years. I like it when in Westerns the 7th Cavalry Regiment says: “We’ll leave at dawn.” I love this lack of precision. Its perfect opposite is timing how long you’ll take to read a text.

Because, here’s a secret: when we take the eyes off a text, that’s when we really read. And that’s the secret of reading. A film (at least at the cinema) takes place in an hour and a half while you look at the screen. It doesn’t stop. On the contrary, when you read in a book by Cabrera Infante: “Those who can make a joke, a poem and a song with two words and four letters also die,” and you can’t help looking up and thinking about all the people you’ve lost who were like that, you’re reading. Those minutes, in which you are absentminded, focusing on a dead spot, encapsulate, precisely, the mystery of reading, its magic.

Tom Spanbauer, followed by his pupil Chuck Palahniuk, offered a writing method called Dangerous Writing. One of its points, which he called Burnt Tongue, consisted precisely in twisting the tongue and writing a paragraph in a funny way so it wouldn’t be understood. For the reader to have to go back and read it several times in order to try and guess the code. In this intentionally tedious text there are a few, by the way.

Francisco Casavella talked about how he had understood, thanks to having learned James Brown orchestra’s stops beforehand, to understand ellipsis in Stendhal’s Le rouge et le noir, when those points of ellipsis equal a night of love in the bedroom. We have to lie down on those dots. Complete them with our own imagination. That’s reading. And the shag hidden and condensed in those three dots can be much more pleasurable, lustful and long, almost tantric, than the most detailed description, with hairs and bites, in Fifty Shades of Grey.

Those three dots, which have such bad PR as the lazy or the dilettante, and are as out of time as an insect inside an amber ball, stretch the secret of why we should read as if there was no tomorrow and no clocks telling the time.

3.