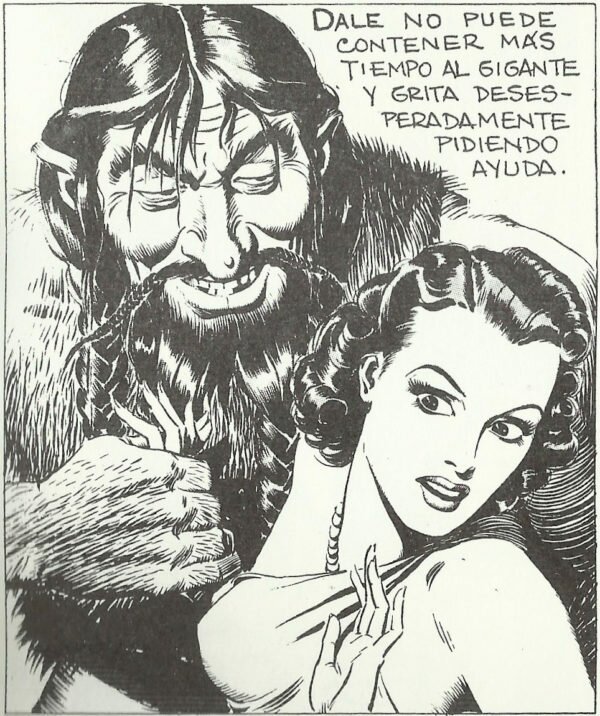

Jordi Costa says farewell (only for a while, don’t cry) to his section Stolen Cartoons with an image from Fred’s Castaway on the Letter A. And?

Today: Fear of a coarse man

By Jordi Costa

Cartoon readers from my generation got part of our education from the rough and hostile territory of plank re-setting, strident colouring and, often, translating outrage, but still, among so much distortion, we managed to develop a solid love for cartoons and similar art forms.

Let’s think, for instance, of the Disney stories published, in their very own style, by Ediciones Recreativas S. A.: yes, they juxtaposed pages, clumsily re-drew cartoons and omitted, among others, the name of Carl Barks, but, as an added value, a classic as huge as Lost in the Andes!, originally created by Barks in 1948, landed here in 70s newsagents under the unbelievable title Andes lo que andes no andes por los Andes (No Matter How Much you Walk, Don’t Walk Over the Andes): it wasn’t the only funny translation case, it seems that in Norway this adventure starring Donald Duck and his nephews generated a curious linguistic debate for other reasons. We met Marvel superheroes mutilated and in black and white thanks to Vértice’s editions, in those covers by López Espí that in time have become fetish and nostalgic collector’s items. We got to meet Jabato, Capitán Trueno and Inspector Dan through the Bruguera editions that creatively combined the pages of landscape comic books to create an illusion of verticality, etc., etc.

All that rushed education didn’t prevent some of us from ending up growing as real page composition and true colour fundamentalists. I can’t to get too mad at Ediciones Recreativas, Vértice and Bruguera because, at the end of the day, they were there, with their clumsy hands and bad practice, when they were really needed, but I do go berserk when, nowadays!!!, Random House publishes a deliriously recomposed Crepax’ Valentina or a landscape Paracuellos I just don’t get how it was even approved by its author.

In those childhood years, there was a man who already lived in another sphere and whom I think will never be fairly vindicated: Luis Gasca. He was one of the pioneer comic strip theoreticians in our country, and both through his essays and his publishing projects he revealed that he was also a Man with a Mission: that of teaching the masses about the excellence of, to use a label from those times, the Ninth Art. Gasca was the thinking mind behind several publishing ventures that, back then, were trying to prove that comic books were more than just a banal escapist instrument for kids, and did so not only defending its avant-garde nature, but also establishing illuminating bonds between its past and the most extreme forms of its present: Buru Lan Ediciones and Pala were oasis of sophistication before the emergence around here of the famous eighties adult comic book boom. Within Buru Lan, for instance, lived together the graphically lysergic Drácula –a magazine that published Beà, Maroto and Enric Sió, among others– with the appearance in instalments –a funny format– of American cartoon classics such as Harold Foster’s Prince Valiant, Lee Falk’s The Phantom or Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon.

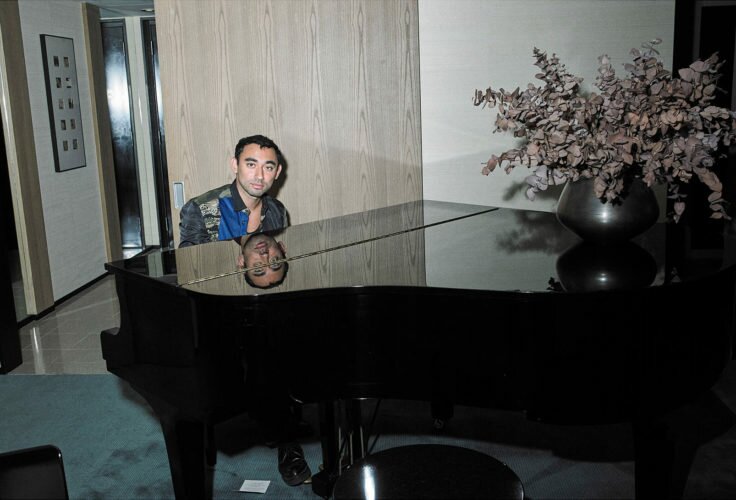

More than once I’ve talked in this section of the purity of childhood fears embodied by a cartoon. I’m sorry, I have no choice but to do it again, because here’s another trauma retrieved from the rich riverbed of traumatic coming of age experiences of the person writing this. The appearance of weekly Flash Gordon instalments was, for me, a kind of dream come true: it seemed the best story ever, with its mixture of sci-fi, Hollywood glamour and sculptural and affected body-language. I was fascinated by its pretentious and Baroque air, even if I was then unable to describe it thus. And, of course, it didn’t even enter my mind that those colours could be intrusive or inadequate, or that the page compositions had been altered from their original landscape orientation to be adapted to the new vertical format. The colours drove me as mad as the rest. Time ended up putting things in place and Ediciones B. O. published years later all that material in black and white and in its original format: from that edition, which is the one I zealously keep –unlike the Buru Lan one, that I lost from sight in a fit of fundamentalism (probably due to lack of space reasons too)–, is where today’s Stolen Cartoon comes from, although the story has more to do with the Gasca edition.

Happiness didn’t last too long. I needed only one episode to fall in love with Dale Arden: when the characters travelled to a north area of Mongo to explore Ice Kingdom and meet the no less beautiful queen Fría (whose name, by the way, was Spanish in the original: I ignore whether it happened the same with her assistant, count Malo) my first fetish obsession started, something that was, by the way, related to the peculiar use of colour at Buru Lan. The characters walked around Ice Kingdom clad on what seemed delicate transparent plastic suits: today I prefer to think these were tulles especially resistant to low temperature filtration. When one sees those same cartoons in black and white, it’s a bit down to the reader to decide whether Dale Arden and queen Fría’s legs are covered by another type of fabric than the supposed shorts covering their groins and pubis, but full-colour instalments left no doubt about it: both Flash and his colleagues were bare-legged under those shorts. I guess that the combination of voluptuous flesh hardly covered by a transparent plastic short over a snowed background short-circuited a perception that, thinking back, in my case had to be necessarily pre-sexual, although no less impressive. Do not trust my memory 100%, though, but I think that, as it happens with those formats, the first two instalments were launched at the same time in newsagents. And then the bloody third one came, entitled En poder de los gigantes (Under the Power of Giants), the cover of which was no more no less than the image of this Stolen Cartoon blown up to become 24 x 30 cm. As you can see, the image showed Brukka, leader of the cavemen who inhabited Frigia’s caves, harassing, in all his manliness, my beloved and delicate Dale Arden. The vision of that coarse man gave me such a fright that I asked my mother to please not buy that week’s instalment and told her that I didn’t want to go on reading that recently started collection, because I was terrified. I don’t know what atavist panic inherited from my ancestors was concentrated in that image, maybe a forerunner of future situations in which a brutal character would end up coming between my objects of desire and me. I, by the way, was six years old.