Teaser posters are, by far, much more suggesting and creative than official film posters. Violeta Kovacsics explains why.

Share

then there

By Violeta Kovacsics

We could think that the turn of the century, and of the millennium even, was no more than a harmless aside on a piece of paper, a footnote, an anecdote to keep us entertained and to nurture implausible theories. It didn’t take too long for us to see how that transition in the calendar was presented as a fissure, as a deep and mysterious crack. The 21st century promised eminently digital films and a wound caused by the fall of the Twin Towers that should change the way we understood fiction and narrative mechanisms. Reality could no longer be the same, the new millennium said. Thus, the turn of the century brought about a series of films that delved deeper in the idea of the fissure. It’s the case of David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (the best film of the 21st century, according to the famous recent BBC poll), in which a nice blond wannabe actress is transformed into a hurt and bitter girl; in which a fragile and amnesiac woman becomes s star about to marry an arrogant director. Its structure in two parts (which, in fact, was a fix: it was a rejected series pilot to which the director added an untimely epilogue) has been seen precisely as the syndrome of the fissure, or partition, taking place in the turn of the century, an idea extended, for example, to Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Tropical Malady.

Critic Michael Koresky described poetically and with precision the kinship between Weerasethakul and David Lynch films: “None of the main characters end up as they once were. Their literal corporeality has simply disappeared; they have been winnowed down to primitive truths. Through myth and indigenous folk tales (of jungle beasts, spirits, Hollywood idolatry) Lynch and Apichatpong offer people stripped of pretence, primal urges manifest in shrieks, sobs, and mewls. In recent American film, the only possible precedence for the overwhelming love story Tropical Malady could be Mulholland Drive”. The dark tale about rotten Hollywood exposed by Lynch in Mulholland Drive is revealed precisely by the crack taking place at the end of the film, when the story is reinvented, turned into a terrible dream.

There’s no film revealing with more fascination, under the opaque blanket of a mystery, the essence of fiction itself as Mulholland Drive, which, at least to me, and still today, is the best contemporary film. Not in vain, it’s placed at the threshold that gave way to the 21st century. For Lynch, the turn of the century is represented as a fissure, in the black hole into which the interior of a bright blue bucket is transformed. It isn’t by chance that the story proposed up to then changes after the visit of the protagonists to a club in which, while the music plays, a man claims that “there’s no band”, it’s all an illusion. Deep down, fractured films are usually an evidence of this, of lies, of the creative capacity of the imagination, of tricks. It’s precisely this what can be drawn from the two tones, a comical one and a dramatic one, of Woody Allen’s Melinda and Melinda, another film underlining the mechanisms of fiction. And also what can be seen in Hong Sang-soo’s films, who has found in fissures, in this case soft and playful ones, in the repetition with nuances of a same story in Right Now, Wrong Then, the boom of a taste for variations that elaborates the ins and outs of the construction of a story. And also what we see in Copie conforme, in which the play of disguises of the protagonist couple goes through an unavoidable tearing in the narrative.

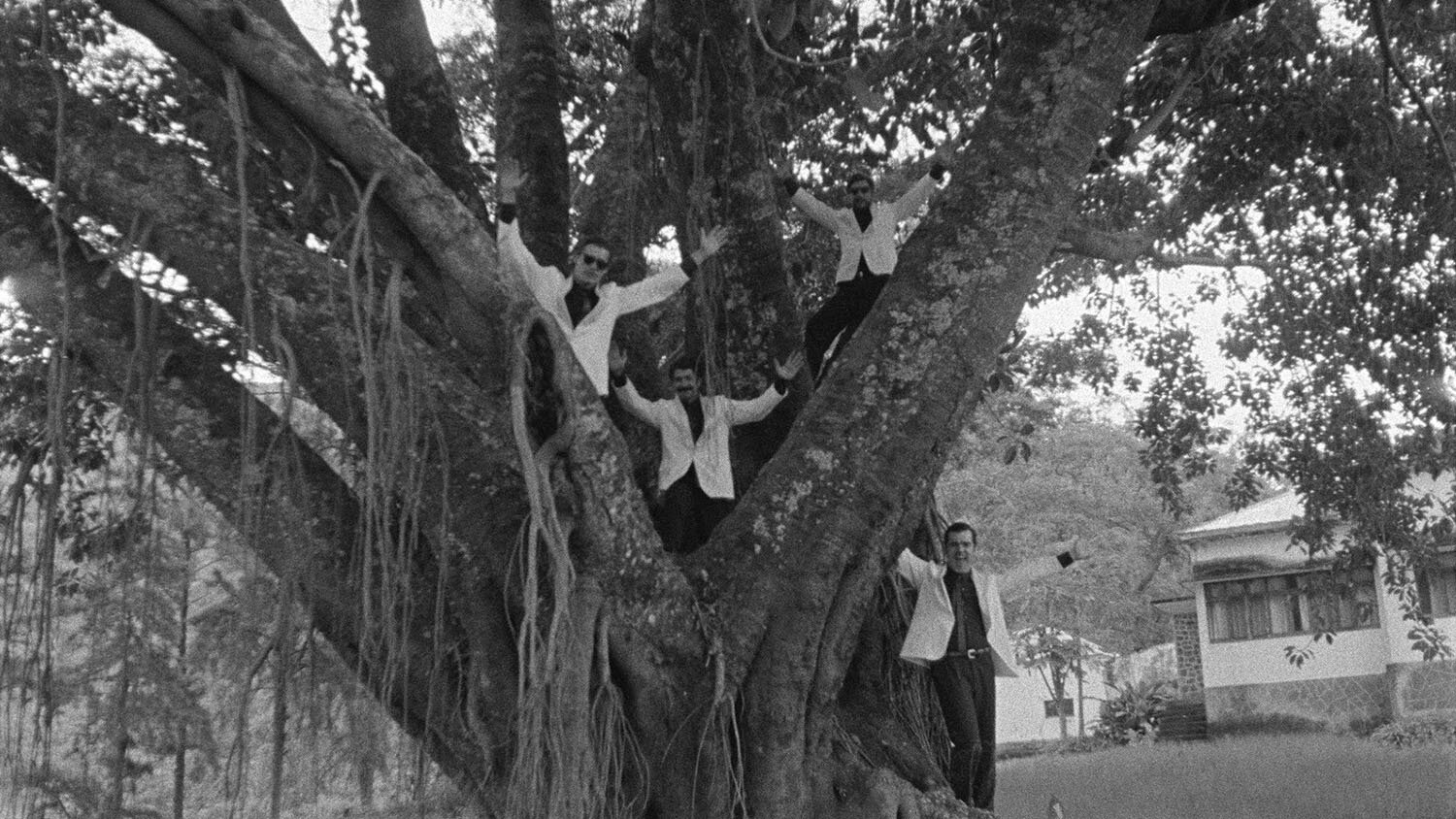

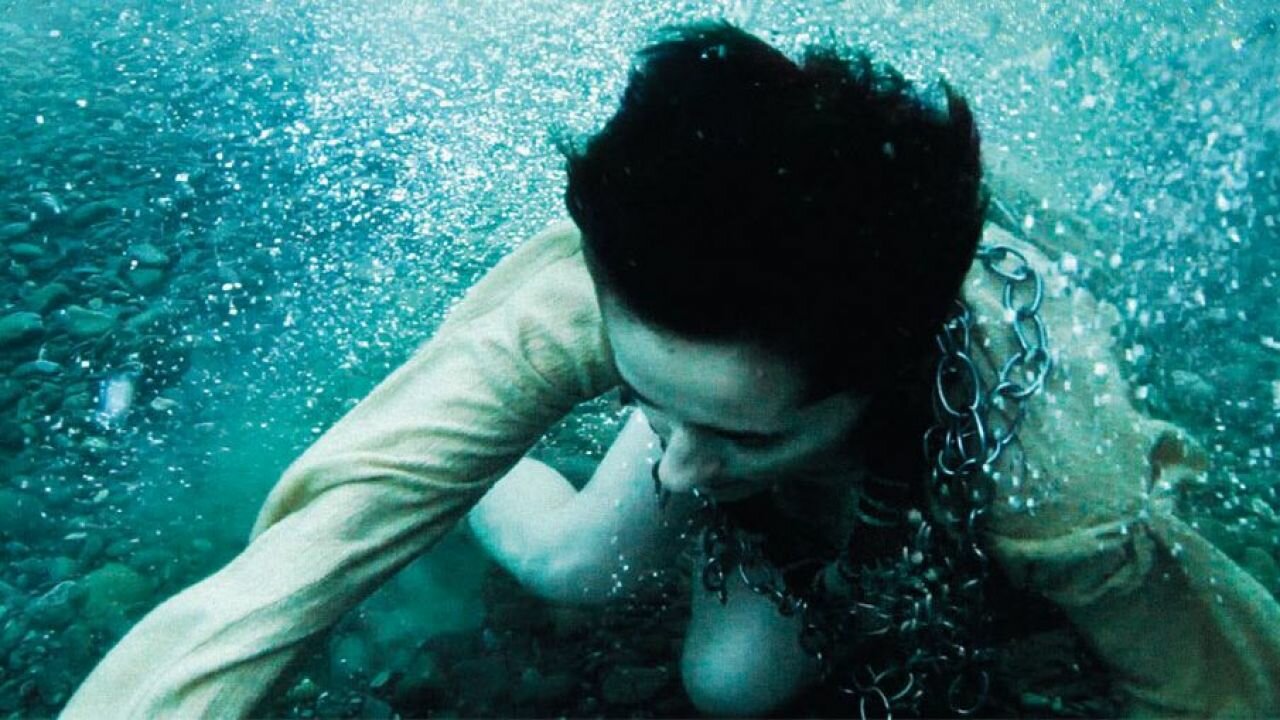

I don’t know if Miguel Gomes’ Tabú would exist without Tropical Malady (maybe not even Aquele querido mes de agosto would exist). Both films have a first half dominated by speech and a certain degree of realism, and a second one that immerses itself in a nature so primitive that doesn’t know of words and in which sound barely exists, only in the form of the murmur of the wind and the trees. Tropical Malady, like Mulholland Drive, moves away from the purely narrative to approach experimentation, because the fracture is above all a crack in the story, a challenge of all logic. The rupture produced has the same effect as anaesthetics. And, when we open our eyes, we wake up somewhere else. In a forest. We’ve abandoned realism to witness a beautiful fantastic drift, with fireflies illuminating a tree, with the ghost of a cow crossing the scene, taking us back to a humanism as mystical as rooted on the earth. Tropical Malady, and Tabú, breaks down to travel from the present to the past, to the construction of a historical and mythological tale.

Gomes has always shown his taste for fragmentation. Weerasethakul has continued digging deeper into the idea of highlighting the equator of the film in Cemetery of Splendour, in which two shots are fused: the one of the escalator in a multi-cinema the protagonist goes to and the one of the room in which the soldiers are resting, as ghosts surrounded by tubes as luminous as fluorescents. The fusion, in fact, has the ability of creating, through the linking of the two images, an abstract, transitory, and suggestive third one, as if it were the essence itself of the art of phantasmagoria that films really are.

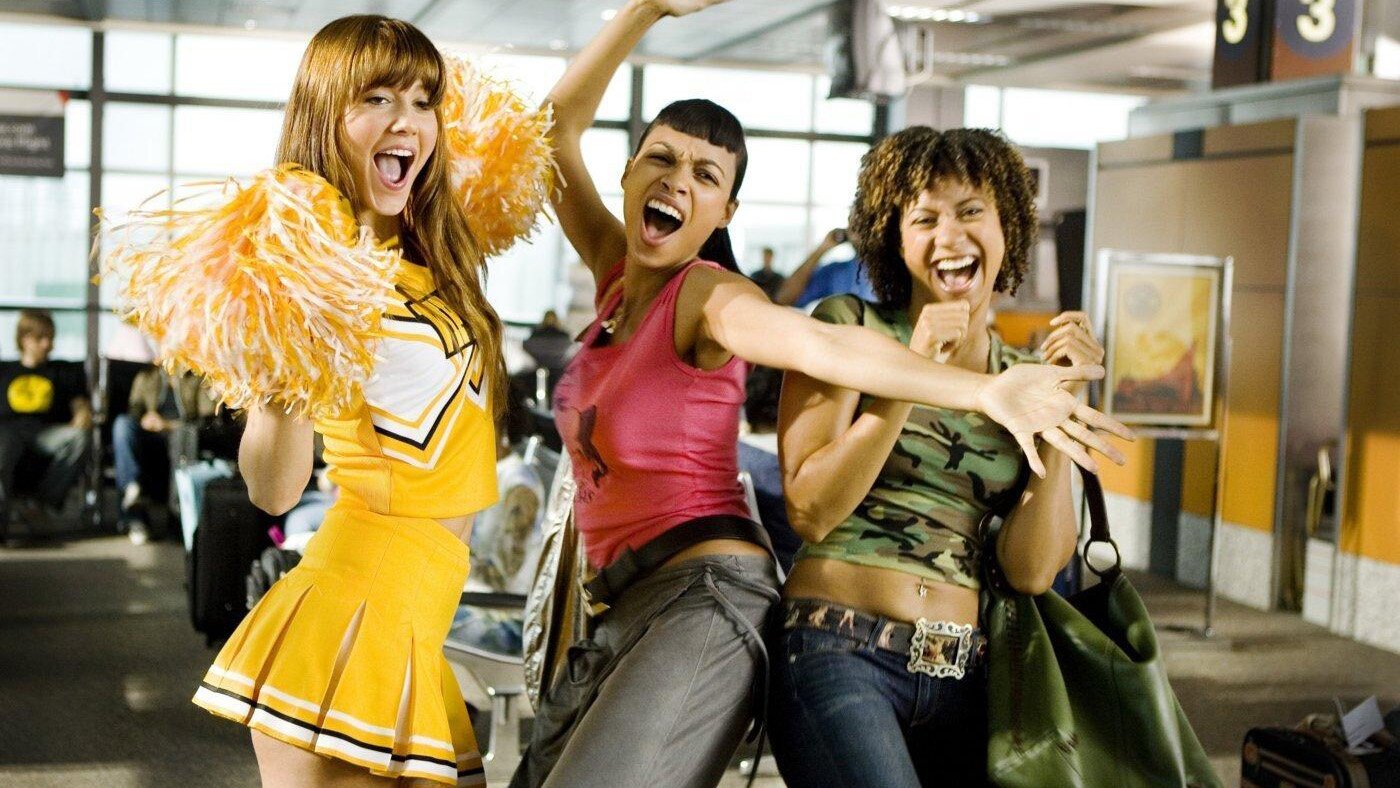

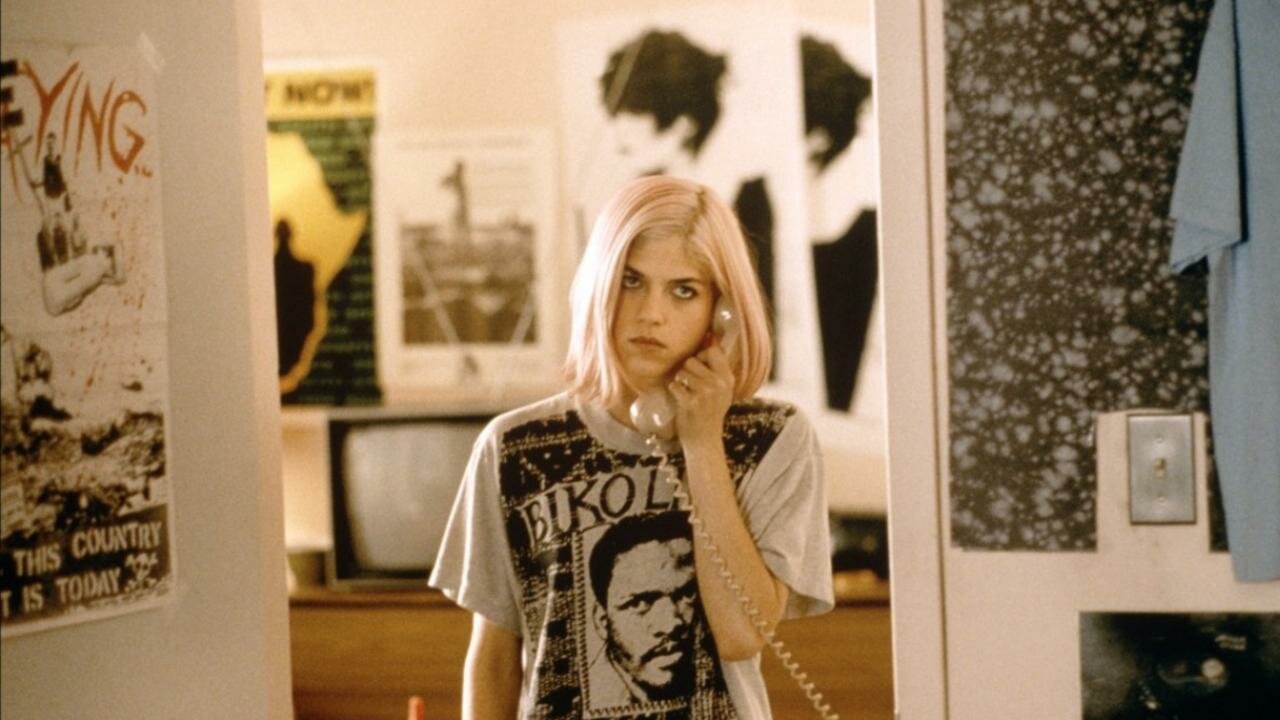

In The Hateful Eight, Quentin Tarantino also suggests a fissure, between a western full of dialogues and the aggressive western, full of blood, the film turns into in its second half. Tarantino had already presented a film fractured into two episodes, Death Proof, in which he exposed two stories with two very different endings in which the texture of the celluloid was made so explicit that we couldn’t help but become conscious of the fact that it was a construct, an evocation, a trick, a distinctly feminist irony arranged by fiction.

Mulholland Drive: The film that turned a corner

.

Tropical Malady: The canon of the crack of the century

.

Copie conforme: And, all of sudden, the show is over

.

Ayneh: Jafar Panahi, half real, half fictional

.

Death Proof: The double face of feminism in film

.

Tabú: Portuguese Twilight + I had a farm in Africa

.

Sangue del mio sangue: Marco Bellocchio and the mirror between past and present

.

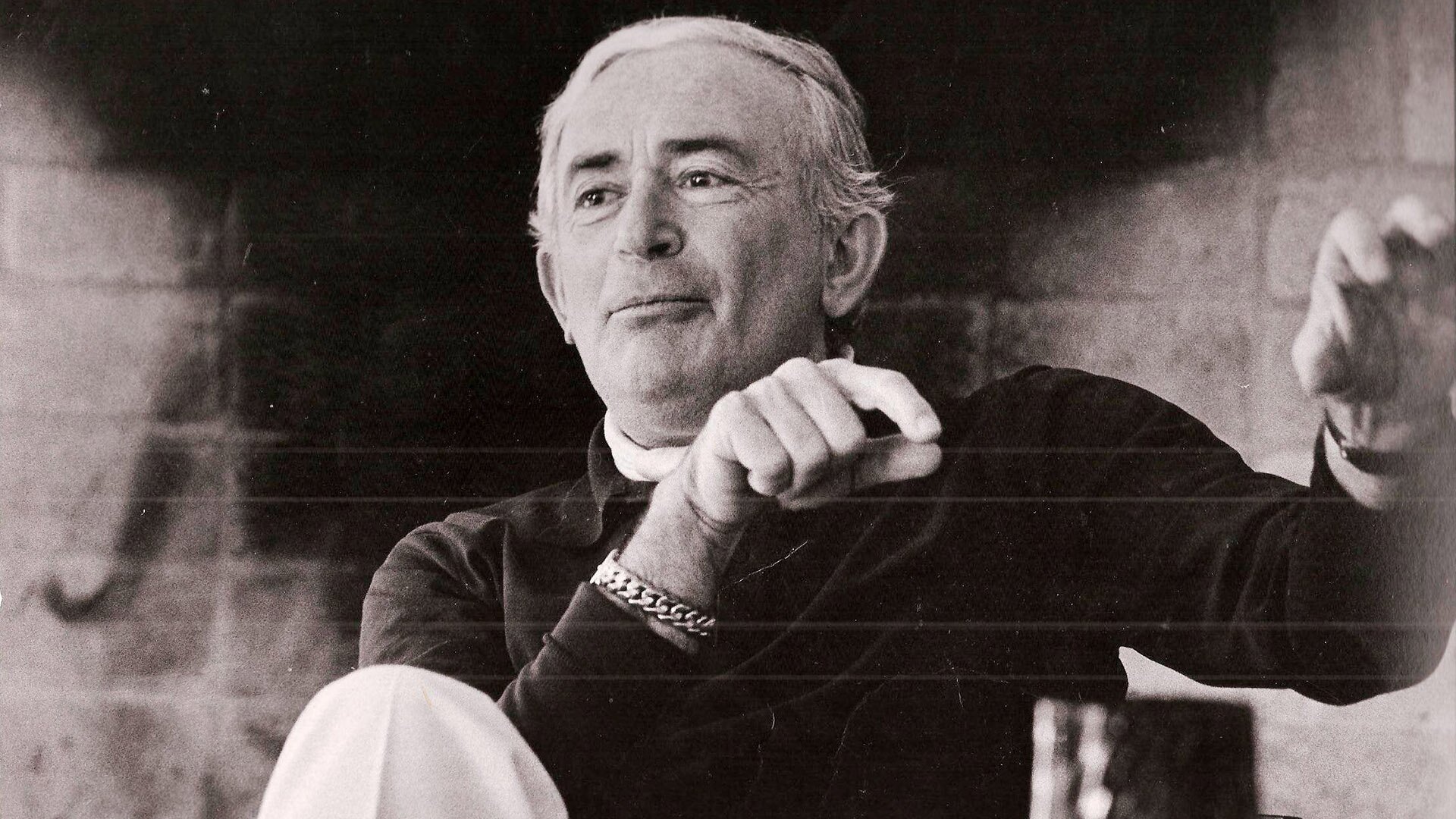

F. for Fake: Orson Welles, a pioneer in splitting stories in two

.

Storytelling: When Todd Solondz was still cool he did 2X1s

.

Melinda and Melinda: Drama and/or comedy