Not only Obama loved Chance The Rapper, as we discovered in his summer playlist: Ben Tuthill also ended up finding some pleasure in the tackiness of Angels.

DRAKE

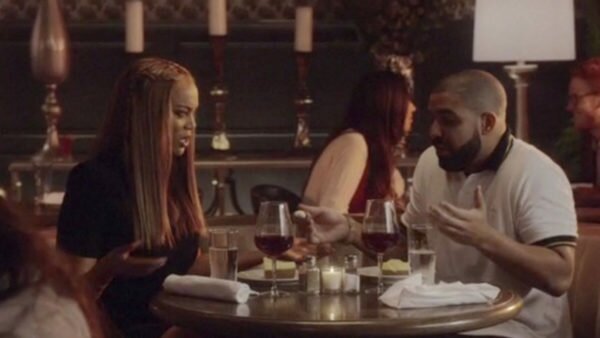

Two minutes into Child’s Play, Drake‘s latest music video spectacle, a man known to some as ‘Aubrey’ utters what might be a career-summing truism. Glancing around a Cheesecake Factory, he says to his stand-in girlfriend Tyra Banks: “This is, like, the nicest one of these I’ve seen”.

It’s a confession of unconditional bullshit. This is the kind of thing you say when there really is nothing left to say. A Cheesecake is a Cheesecake. A model girlfriend is a model girlfriend. A Drake song is a Drake song. You don’t even need to step back to see that it’s all the same.

Drake’s confession serves as thesis statement for the entire video. Child’s Play is a bloated twelve-minute presentation of everything we’ve already seen self-consciously spun into its own opulent un-specialness. It offers nothing to distinguish itself from every other Drake video. It’s the visual equivalent of the “you da fuckin best” that launched his career. Of course she isn’t da fuckin best. Of course the superlative is devoid of any ontological specificity. Of course Drake is full of shit. It’s the meta-analytical anxiety on which he founded his brand.

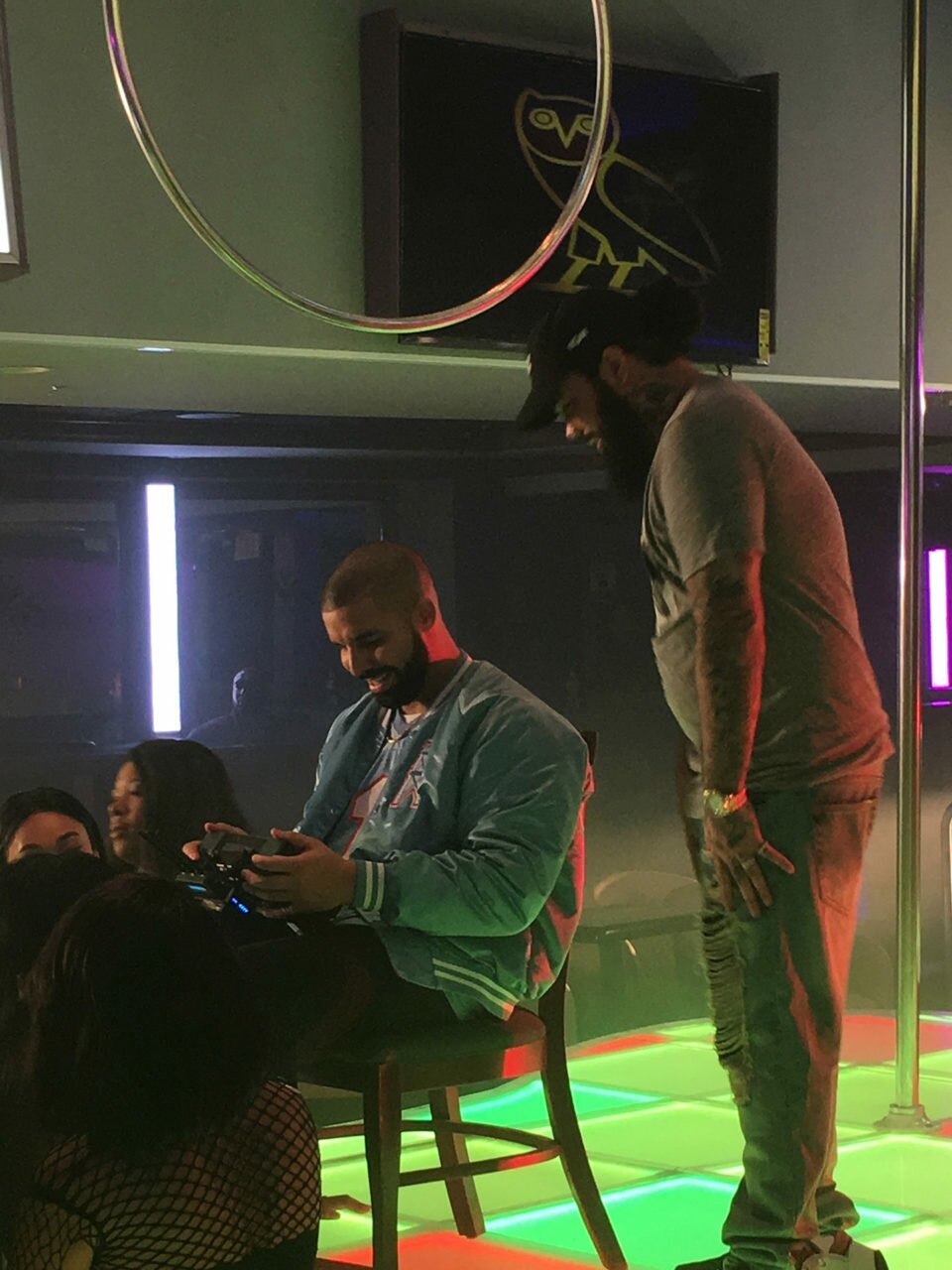

The video for ends with a women’s basketball team coached on nothing but fawning praise being crushed by a team with actual talent – a simple exposition of the millennial “everyone gets a trophy” condition. Child’s Play ends with a similarly millennial tragedy: Drake onstage, surrounded by women at a Houston strip club, looking like he’s ready to fall asleep. Really, the two scenarios aren’t all that different. Both place a mimetic of achievement over any real substance, and both collapse under the weight of their own worthlessness. A shelf full of participation trophies, a Worldstar front page full of strip club videos – which better portrays a hopeless grasp at worth?

Child’s Play‘s disappointment is a fitting period to Summer 2016. This was the most hyped summer in recent memory – three months in which every event treated like it was the beginning of a bold new era. Going in there was so much potential for newsworthy disaster – political tensions were at a twenty-year high; a long-brewing feud looked ready to explode; the Olympics looked ready to go up in flames; Boys Don’t Cry was maybe actually going to finally happen.

What did we get? The pre-ordained candidates got their nominations. Kim Kardashian created another one-week clickbait cycle. We had two weeks of horrible, horrible news. Michael Phelps and Usain Bolt won their medals. Frank Ocean released his record to mandatory critical acclaim. And in the end, Drake went to the strip club in Texas with the remnants of a chain-restaurant cheesecake splattered across his face.

There were a million things to be said about all of these things, and all of them were said. By the end, the commentary starts to blur together, a continuous string of off-hand comments treated as thoughtful criticism. The events blend with the reportage – the reportage deliberately emulsifies the blend into a paste. There’s a narrative, but it’s every narrative, different for every individual who tries to follow it but still ultimately the same never-ending sequence. It’s invigorating in the future tense and exhausting in the past.

It’s natural to be exhausted at the end of summer. But Child’s Play‘s exhaustion is less the result of a few months of sweaty activity, and more the existential crash that comes when you realize that the activity is never going to end. The hype will keep going. The news will keep replicating. The releases will keep coming with a slightly revamped layout and the same old menu.

A few days before Child’s Play, Vince Staples released a Nabil-directed long-form video set to a medley of songs from his new EP . Like Child’s Play, Staples’s video is a meditation on saturation and claustrophobia. Prima Donna offers up ten minutes of recognizable music video tropes, all blurred into an exhausting stream of meaningless noise. There’s an African warrior in traditional dress. There’s a red-lit room. There’s a motel hall of doorways. It’s a confusing and frustrating and boring eight minutes, and it concludes peacefully in an open field with Staple’s lying on his back, staring at a quiet sky. It takes a moment for it to become clear that he’s bleeding out the back of his head.

Entrapment and escape through suicide is no newer a trope in popular music than post-break-up strip club visits. But the repetition only serves to underline the message. There’s something boring about an unceasingly remarkable life. Both for the people at the center of the story, and the people who follow it. Child’s Play, and Prima Donna, and all the relics of the summer of 2016, are reminders of the boring damage we’ve done not only to the objects of our fascination but to our sense of fascination itself.

If pre-break-up restaurant dialogue can teach us anything, it’s that the best way to avoid saying what needs to be said is to make mandatory a conversation about something completely worthless. Tyra Banks, in response to Drake’s Cheesecake observation, says, “Yeah, it’s a good one, yeah”. She then proceeds to go through the motions of every hypothetical spurned lover that Drake has ever had. What’s absent in her rant is the question that every one of us should be asking ourselves – why the fuck are we at Cheesecake?