For Henry J Darger, Mykki Blanco’s Loner and Arca’s Reverie redefine the body, the limbo and sexuality in music videos. And, as usual, he’s right!

FARAWAY,

Illustrations by Irene Pérez

Text by Carolina Prada

SO CLOSE!

— I’ve tried to strip a bit of paint off the wall, but I didn’t dare to.

My friend is just back from the toilets. He sits down and takes a long drink of his beer. I look at him and think aloud:

—Maybe we’re overdoing this whole groupie thing…

—But Bowie and Iggy probably did coke on that loo! —he replies.

We’re at Neues Ufer, formerly Anderes Ufer, the café-bar in which, indeed, David Bowie and Iggy Pop shared conversations and nights out when they lived in Berlin at the end of the seventies. It is, in fact, very close to their apartment at the . It’s a nice place, with the multi-coloured gay pride flag hanging outside, candles and flowers on the white marble tables and walls covered with photographs of the many impersonations the singer adopted throughout his life.

It’s Saturday, and we’re at the end of January. Bowie died a few weeks ago. He’s the reason of our trip to Berlin (and of many people’s, it seems, judging by the amount of customers who are undoubtedly here because of him). A sort of pilgrimage to say goodbye to the man who changed rock forever and also, to a large extent, our lives. Following his steps around this city, so important in his career, makes us feel somewhat closer to him.

The British artist was seduced by the strange atmosphere of a city in a state of war which, even without knowing it personally, inspired his friend Lou Reed to create the sombre and magnificent Berlin. He was fascinated by the legendary cabaret and avant-garde past of the Weimar republic, but also, contradictorily, by chic fascism and Nazi imagery, for which he would be reprimanded later on.

Bowie perfectly combined his lazy party animal side spent in clubs such as SO36 or the one owned by his confidant and lover Romy Haag with creative work done in his apartment, where he spent long hours composing, painting and listening to music. He immersed himself in electronic music and krautrock, specially Neu!, Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream; reading Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin novels; and learning about German expressionist painting, in particular, the work of Erich Heckel, included by the Third Reich in its ominous exhibition they designated as “degenerate art”, which exercised a great influence on him. The photograph by Masayoshi Sukita illustrating the cover of is inspired in two of the painter’s works: the oil on canvas Roquairol and the print Young Man.

Through the window of the café we can see the grey skies one can expect to find in this city’s winter, as portrayed in Wim Wenders’s films. We feel quite cosy inside so we decide to order yet another huge beer. Now we’re a bit tipsy and feel elated and happy.

The waiter is a nice guy who tends to the tables in his own time and stops by a while to talk to the customers. He brings us the beers and some salty sticks as a side snack. Without thinking, I aske him if he ever met Bowie. “Hahaha… I’m not that old so as to have worked here in the seventies!” I realise I’ve been a daftie. “Don’t worry, you’re not the first person to ask…”

Fucking fans…

After successively getting rid of the Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, Halloween Jack and The Thin White Duke skins and living on a red pepper, milk and cocaine diet in Los Angeles, Bowie decides to move to Berlin with his friend Jimmy Osterberg-Iggy Pop. His marriage to Angie is about to blow up. He wants to quit drugs and give its music another turn of the screw: “A new career in a new town,” as he entitled one of the instrumental tracks of his album Low.

“There came a time when I was very, very worried about my life. I came close several times to overdose,” the musician remembers about that time in BBC’s wonderful documentary Five Years. “I went naked in Berlin. I tried to reduce my life to what I thought were the essential basics so as to be able to build it again.”

And although trying to rehab in the vibrant Berlin nights of the end of the seventies with the likes of Iggy must have been improbable, to say the least, it seems that it more or less worked.

Musically, with the so-called Berlin trilogy, he completely departed from what he had done before. He found the inspiration he needed in the German city and surrounded himself by the ideal accomplices -Brian Eno and Tony Visconti- to compose three brilliant albums, the most experimental ones of his career: Low, Heroes and Lodger. And let’s not forget the two Iggy Pop albums in which he worked side by side with him: The Idiot and Lust for Life.

Writer Paul Trynka says in Starman, his thorough Bowie biography, that he and Eno called Tony Visconti to work with them on Low and . “’I was placed in a predicament so I had to make something up quickly.’” Visconti answered that he had discovered the Eventide Harmonizer, a new system of digital delay […]. The explanation he gave them about the new device was that it fucked with the fabric of time.’ So they accepted it.”

In fact, Heroes is the only vertex of the Berlin trilogy entirely recorded in the city, at legendary studios , as they appear on the album’s credits. Low was mixed there, but it had been recorded in France, at the Château d’Hérouville -where, by the way, Bowie, Visconti and Eno swore to have felt the presence of the ghost of the old inhabitants of the place, the composer Frédéric Chopin and his partner, George Sand-. As for Lodger, although it shared the same spirit and creative team as the former two, it was recorded in Montreaux. This album also brought about the dissolution of the trio. Bowie and Visconti worked together again on Scary Monsters, but would not do so again until Heathen, already on the 21st century, while the singer and Eno would liaise again in the nineties, with Outside.

For anybody interested in music, and for fans of Bowie, Iggy, Eno, Nick Cave, Depeche Mode, U2 or any other band ever to record there, Hansa Studios are music’s Sistine Chapel. For that reason, we had to go visit them at all costs. When David died, they opened their doors freely to pay him homage, but usually the only way to access them for anybody is to join a guided tour.

Hansa Studios are located in a quiet street next to Postdamer Platz. In 1977, the surroundings were ruins and perfectly portrayed the city’s war zone ambience. The formerly elegant building offered a desolate aspect, with part of it demolished and merely two-hundred meters away from the barbed-wire fence of the Wall. From the studio one could clearly see a watchtower and soldiers controlling everything with binoculars. It’s easy to imagine the musician’s working conditions.

We meet our guide, Thilo, an old sound engineer who seems to know the place perfectly and speaks passionately about all the musicians that have recorded there. He seems a bit of a freak, but… aren’t we all the ones doing the tour as well?

We make up a varied group of some twenty people of different ages. There’s a guy who seems a mixture of the Iggy from The Idiot and a cramped version of Bobby Gillespie. A girl in a wheelchair listens patiently to what Thilo has to say, although it’s obvious that the big fan is really her boyfriend. Thilo speaks English really fast and sometimes we get lost, although what he has to say is really interesting and so we enjoy our visit.

We enter with reverence inside the elegant Studio 2, “the big hall by the wall.” It’s an impressive and huge space and back on the day it was used to hold Nazi chiefs’ balls. It doesn’t look like a recording studio at all, among other things because it lacks the big glass windiw separating technicians and musicians. The freak guide tells us that during the recording of Heroes they used TV monitors to communicate with the technicians, who were on another studio upstairs. He shows us several images in which we see David with the sound engineer, Edu Meyer, with Tony Visconti and with guitarist Robert Fripp.

Being at the place in which a was born is quite thrilling; from this window, Bowie saw Visconti furtively kissing backing vocal singer Antonia Maas and thus found the verse he was lacking for the lyrics to Heroes. Ten years later, thousands of East Germans could listen to it and sing to it from the other side of the Wall, during the notoriously disastrous Glass Spider tour, in a night that ended up with a violent police action and with almost two hundred people arrested. The Iron Curtain wouldn’t fall until two years later.

We then move on to Studio 1, currently in use, and go mad like little children with all the mixing decks full of knobs and lights. Thilo plays some of the masters of songs recorded there. Dave Gahan’s voice in People Are People and Black Celebration, Iggy’s in The Passenger and then David’s in Heroes inundate the room and give us goose pimps. The sound is amazing!

My friend and I have been possessed by the Japanese tourist spirit and get out of there with like one hundred photographs each.

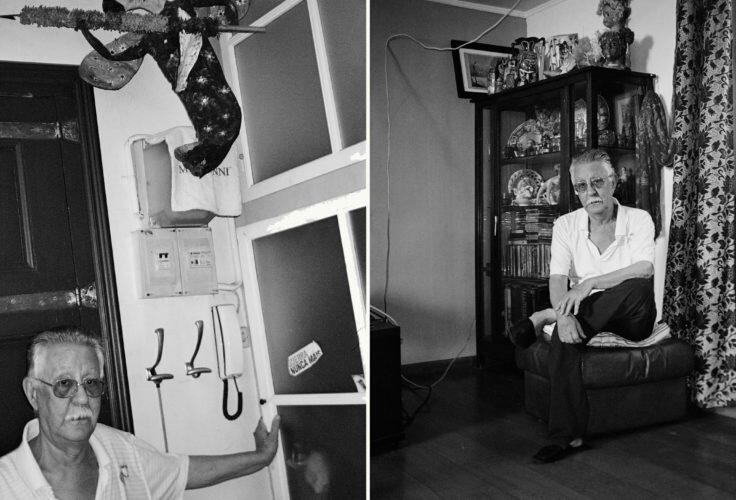

We’re staying at a small hotel in Schöneberg, the same neighbourhood in which the apartment that David and Iggy shared (we’ve heard that in fact they lived in two different apartments in the same block; we’ve not been able to find out the truth) is located. A gay area both today and in the seventies, at Nollendorferplatz there can still be seen a plaque with flowers to remember the homosexual communities killed by the Nazis. Both friends used to visit the antique markets of Winterfeldtplatz, and the bookshops and cafés around St. Matthias Kirche. Trynka’s book includes Iggy Pop’s impressions from the time: “It was a learning process, we always had the idea that we were trying to learn something here. And we were quite disciplined about it.”

Hauptstrasse 155 is the last stop in our fan route before leaving the city. We carry a poster with a picture of David as a really young mod and a notebook in which many friends and ourselves have written farewell messages. We also buy a rose at a florist when we get out of the tube. Since we’re at it, let’s do the whole thing!

As soon as we get closer to the place we see the huge amount of candles, flowers, drawings and photographs that overflow the door to expand towards the nearby tattoo shop and physiotherapy clinic. Seeing all that on the pavement gives us mixed feelings: it’s thrilling and depressing.

A fan has placed a picture of her with David; others, portraits and drawings of the singer in his different personas. Emotional words from people that feel, as we do, like orphans. They have even “given” him a bottle of red wine.

An intense rain starts falling over our heads and it erases some of the messages written with felt-pens. Despite of it, some Bowie-addicts and curious people remain, silent. A car parks on the other side of the road. From it comes a family with lots of shopping bags trying to access the door, probably sick of seeing a similar big group of intruders in their building day after day. “And this isn’t going to stop anytime soon!” we think.

We take millions of pictures (the Japanese tourist spirit strikes again). We leave the flower, the notebook and the poster and leave the place feeling a bit sad, like when you come back from a funeral.

I think of the songs in Blackstar, his last and dark album, which he published only two days before he died. And also in some words pronounced by Igor Paskual, a great admirer and connoisseur of his music: “The packaging of Bowie’s music is like a key that opens the doors to many rooms. Listening to one of his albums from beginning to end is like a walk on the world of fashion, art, architecture, film, literature and music videos, and you can live in his albums for a long time.”

—And on the world of feelings, above all —my travel companion adds.

You could live forever in his records, why not? It would be a good life.