Eddie Izzard is an extraordinarily unique comedian: trans, learned and really funny. Kiko Amat interviews him during his last visit to Spain.

An interview

By Kiko Amat

“I want all my work

to be fun and

at the same time a

bit avant-garde”

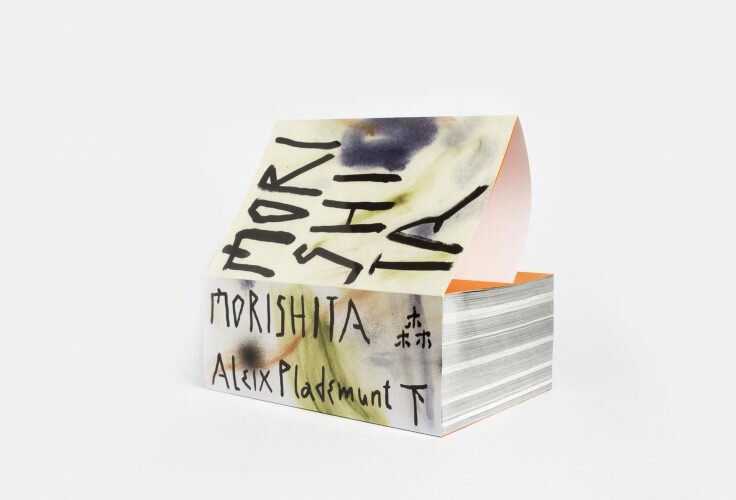

Richard McGuire was born in 1957 and he’s a writer/cartoonist and bass player in memorable early eighties New York band Liquid Liquid. Don’t frown just yet! You have surely danced to his bass lines, at least to those of their song , which was sampled by Grandmaster Melle Mel in the rap hit . McGuire, a real “multidisciplinary” artist –that is: not someone who does all sort of things and they’re all crap, as it often happens in our country, but does them right–, have been drawing for quite a few years now and his idea for Here, the comic book that is bringing him all sorts of prizes and congratulations, dates back to 1989. It was then when he published the 6-page version of the same work on the pages of Art Spiegelman’s RAW. Like You Really Got Me, some things in life are brief yet very influential.

The idea of that Here was the same as the idea of this Here (extended version): the story of a room, and of all those that roam about it during hundreds of thousands of years. Yes, you read that right: the book includes the beginning of the universe, the extinction of the human race and a certain Benjamin Franklin, but also a man who’s lost his umbrella, a broken glass and a choking relative. It’s all here: galactic and mundane, in a way few artists had managed until today. That’s what I call achieved ambition.

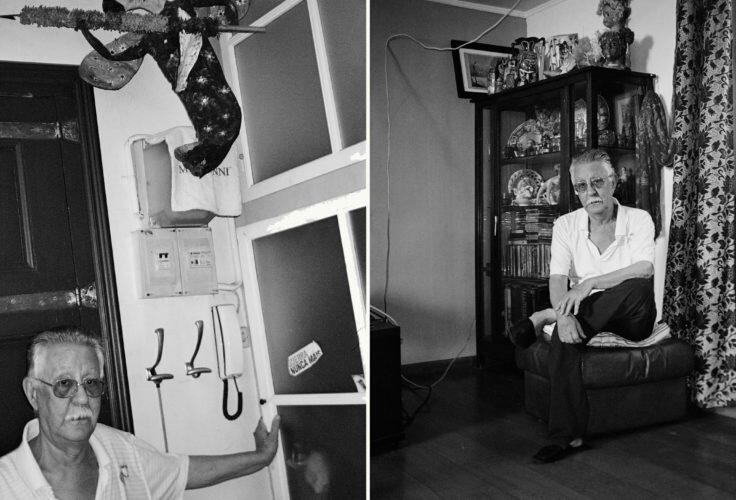

I meet Richard McGuire at Barcelona’s Design Museum, in the biggest empty room I’ve ever seen (yep, I’m a bumpkin). In a corner of that cyclopean überloft we sit down, and from a distance we might resemble a scene taken from one of his cartoons. Two guys overwhelmed by their surroundings, conscious of the smallness of the human race.

McGuire is a charming gentleman, nice and generous, a fifty-something that doesn’t look his age and who laughs at all times narrowing his oceanic turquoise eyes and talks with a soothing voice that anyone suffering from AMSR would love to bits. A guy that doesn’t take success for granted, but receives it with gratitude, humility and a good soul disposition. Someone with lots of anecdotes, ideas, dreams and projects to tell. The perfect interviewee.

How did you grow up, how was your childhood like? Did your family have artistic aspirations?

My mum was a librarian, and my dad an accountant. My mother always encouraged us to visit museums and cultivate ourselves. I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately, since a friend told me that I had been talking about Here for too long and suggested I gave a talk without mentioning the damn comic book! I was dubious, what am I going to talk about then? But in the end I decided to select fifty things I liked a lot, and talk about them for an hour. I structured this in a way that it ended up as a kind of biography, with lots of things that have been important in my life.

In all sorts of spheres or only art? I mean, like your grandma’s cooking or something as well?

Yes. Well, not that, but almost. They had to be brief pieces, because they all needed to fit in sixty minutes. So from a song you could only hear a fragment: “hey, pay attention to this bass line, [he pretends to be putting a record on], “Walk on the Wild Side”, listen to both bass lines crossing…” And then I would switch it off after a minute. I analysed that kind of stuff and all of a sudden lots of fundamental things in my life came up to the surface. For example: when I was around five years old, my mum kept a notebook with pictures of famous paintings, and we played at guessing the name of the artist and the title. Digging for artefacts from the past for my talk I recalled that one of those paintings, by Vermeer, had been unconsciously included in Here, many years later. I must have carried that painting in the back of my mind and then it popped up again when I created Here.

So there was music too during the talk? Did any familiar music you didn’t remember pop up as well?

My mum studied music composition, yes, and there were always instruments at home. We had a piano. I always felt I could try different instruments: guitar, keyboards, whatever. But I never received a formal musical education; I only did it to have fun.

What would you say was your musical epiphany? On the comic book you include a song by Peggy Lee I really like, , for example.

That Peggy Lee song comes from someone I used to know, Daniel Melgarejo, a very funny guy who was also a great cartoonist, illustrator and animator. He was the first person from my circle, someone I closely knew, who got AIDS. I remember him singing that Peggy Lee soon after he had gotten the news, you know, “is that all there is?” and that’s why I put it on the book. He accepted his “death sentence” with inspiring grace and humour. But speaking in more general terms, my heart was always divided between art and music, I always went from one to the other [he does a hopping gesture with his hands]. When I was a kid I loved the Beatles and collected all sorts of things related to them. Today I’m still a big John Lennon fan and I realise that many of the artists I admire went to art school, like I did.

English art schools from the beginning of the sixties are a map of who would be relevant in pop a few years later. All R&B bands were ex-art school students, mixed with he occasional criminal element.

[Big laugh] Of course! But at the same time I think of the past and I find many other influences on top of the art school. I’ve always been exposed to art and since day one I wanted to be an artist. That was the most important thing for me. I remember myself always hungry for more art knowledge. I spent the day at the library, searching among books and yearning to understand, reading about all kinds of artists. One summer I joined a course, when I was still a teenager, during my high school years. They were extra-curricular art lessons, and there I met an artist that would become very influential in what I do. One of the first things he told me was: “Art never leaves art. Art should never be for art’s sake. It should leave the art world.” I took that very, very seriously. I ended up going to university, outside New York, and there I studied (as it was to be expected) art [he laughs], but I met, and tried to meet, the maximum amount of people outside that world. And some of that people would end creating the band with me. Weird people, to put it somehow [he laughs]. Perhaps if I’d followed the traditional way the bad would have never existed. I don’t know.

I think your approach is the most advisable one. John Fante said that a writer should never mix with other writers, or at least not exclusively mix with them. He believed it was bad for writing and for the spirit.

It’s a good piece of advice. When I went to university that was exactly the situation, and what I tried to avoid, in fact. I moved to New York as soon as I could, I had always felt that gravitational tension towards the city. I grew up in the suburbs, 45 minutes away, in New Jersey, with my parents, visiting one museum after the other. I always wanted to live there. During my first two weeks in the city I started meeting people and making the types of friends I would have made should I’ve been to a New York college. A while before permanently moving there I was already working, again as it was to be expected, at an art gallery [he laughs], so I would daily commute from New Jersey to New York by train. It was the time in which graffiti, back then a new art form, had invaded the urban landscape. I moved to the city in 1979, more or less the peak time of graffiti in New York. Trains were literally covered with graffiti; it was all very mysterious and strange, I was completely fascinated. And although I knew I wasn’t a part of that, I wanted to somehow respond to that external impulse. When I moved to New York I was already rehearsing with what would become Liquid Liquid. I just remembered us at CBGB, shyly asking the guy whether we could play there one day [he laughs]. Still in 1979, in September, we gave our first concert. We stil called ourselves Liquid Idiot. And what I wanted to tell you is that I designed the posters for the Liquid Idiot concert and stack them everywhere, but at the same time I did some art signs to stick out there. If you check my Instagram account you’ll see a picture of me in front of one of those huge signs, in 1980. I did them with stencils, spray and black chalk. Through those signs I ended up knowing Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, long before they became well known. They were just a couple of guys I would run into in clubs, and they’d seen my signs in the street and so they ended up coming to introduce themselves. Basquiat was already doing his SAMO graffiti, and in my eyes that made him a great artist. He was SAMO! [he laughs] One night we were playing at a club… No, it wasn’t a club, in fact, because we still weren’t allowed to play in conventional clubs. It was a party at a loft, and several bands were playing. One of them was Gray, Basquiat’s band. We met there and became friends. He sold painted T-shirts in the street and was broke, but to me he was a superstar. And now I realise that I completely lost the thread there! [he pisses himself laughing].

You were saying that those unknown artists were already famous characters in your circle. I imagine your scene like a secret society, like something nobody knew. In a recent interview you defined all you did then like “difficult to find”.

You better believe they were difficult to find! [Vehement]. I don’t think something like that would be possible now: times are very different… New York, back then, seemed a lot smaller. A village. For starters, when I got there, there weren’t many places to play or watch gigs: CBGB, Max’s Kansas City…

Hurrah…

Yes. Hurrah was an old disco that started scheduling many English new wave artists, and seeing them was amazing! But even buying albums was something strange and difficult. Few places had imports, and when you found something it was considered a rare find and you would immediately share it with all your friends. When you had access to that small city you knew everybody, because we all ended up going to the same places… I don’t know whether you’ve seen , that funny film about New York’s art and music scene from back then. Seeing it today is a shock, because for starters you realise that the Lower East Side was a dump, it looked like a war zone. Crime, very hard drugs, a horrible, horrible place. But it’s quite funny seeing Basquiat, the film’s protagonist, going from club to club. There isn’t much of a plot to it, but you get a glimpse of the way things were back then. At the time, I bumped into Basquiat one day and he asked me whether I wanted to appear on “his” film. I answered “yes”, I was really thrilled! But they run out of money quite quickly and the film was never premiered, although it was discovered a few years later. I remember that one of the producers apologised to me: “I know you should have appeared in that film and now it won’t be possible. But we will use your music in it.” And, indeed, tow of my songs feature in the film, one when Basquiat is painting a wall, and another one when he’s jumping on a taxi and Cavern is playing on the radio. The good thing is that both are 1983 songs [he pisses himself laughing]. Back to the future! On top of that they lost the sound recordings and they had to dub the voices in all the scenes. Basquiat himself, in fact, doesn’t even speak with his own voice! Seriously! His voice is, paradoxically, that of the actor who would end up playing him years later in Julian Schnabel’s biopic. That was very weird for all of us that knew him. Mmm… [he interrupts himself]. I’m afraid we’re talking too much about Basquiat, I’m sorry.

No, not at all! I find all this really interesting.

What I was trying to say, I guess, is that now everything is different, now you can find everything on the internet. I’m still surprised at how I got to know some things at the time. I was in high school, listening to Patti Smith’s first album, which was very important to me, and also Talking Heads’ first album, which was too, and all of a sudden I would find out who Brian Eno was, because I had heard Roxy Music, and then I learned that Eno had produced Devo… It was a breadcrumb trail that you followed and completed and you kept on. One thing led to another, and that to another, and that way you created a map, a universe of things related to each other, connected.

You can’t even image how much I like what you just said.

[He smiles]. Those things were very important. I listened to the first two Brian Eno solo albums and that was so important to me… It was crucial. And something was still more important: Brian Eno would produce the No New York album, what for me would be more capital, because it indicated the exact direction Liquid Liquid wanted to follow and was already following. At the beginning we were very noisy and we improvised a lot, so when I heard all that I was shocked. I told myself: “These are my people!” [Big laugh]. When I got to New York I saw DNA for the first time, and they were amazing. My favourite, with Arto Lindsay on guitar, Tim Wright’s bass guitar, Ikue Mori’s drums. Also Konk, who were friends; Lydia Lunch, who was then in 8-Eyed Spy…

I tend to imagine early eighties New York, with all the artists and rappers and punk rockers, a bit like a musical, like Hello, Dolly! As if one was walking down the street and kept on bumping into all those artists and cool people: “Hey, Thurston!”, “What’s up, Andy!”, “Last one’s great, Alan!”. Am I idealising the place or was it really like that?

Yes, it was like that, and can still be like that sometimes, and that’s what makes New York so big. Despite its millions of inhabitants, it’s still an island, an the circles are tiny. I think the scene was even smaller back then. All modern and cool people went to the same clubs and art galleries. Graffiti kids South Bronx would mix with Soho artists, art collectors from the upper side of town would mix with Downtown bohemian musicians. I remember seeing Klaus Nomi on the street a bunch of times, even with no make up on he was a dazzling individual. I would bump into Andy Warhol when he was shopping, and once at a party in Keith Haring’s tiny apartment I was with Madonna! I used to love seeing Robert Mapplethorpe and Lou Reed in art gallery vernissages, or just there on the streets. Seen a star unexpectedly is always quite thrilling.

We’ve done an overview of the jam-packed band universe of the time, particularly DNA. I would like you to tell me who were your favourites and why, and also talk about some of the ever present faces of the scene: James Chance, Lydia Lunch, Alan Vega… My favourites, by the way, are Bush Tetras. Long live Pat Place!

We acted as supported band for Alan Vega once, and he was a really nice guy who treated us with deep respect. When we played in Paris for the first time he went to the backstage to say hello. I saw all the people you mention live and, of course, loved them all. They were the “stars” when we entered the scene. It was a lot of fun watching James Chance live, there was always that tension to see whether he would end up punching someone or not. He was famous for that. And I really loved his combination of noise and funk. With Bush Tetras we only played once, as far as I recall. Despite being with the same label, 99 Records, they were kind of distant, but probably it was because we were also very shy. I’ve always thought that Pat Place was the coolest of them all, a great funky musician with an amazing style.

What about Mars?

I never saw Mars, no; they had just split up when I arrived in the city. But I ended up meeting each and every member of Mars, no doubt. It’s funny how you keep on bumping into all those things. The way you hop from one thing to the other.

This is going to sound very old-fashioned, but I’m afraid a concrete type of effort that was very positive has now disappeared from the map, and that came from precisely from what you said about joining all those breadcrumbs.

It might be true. All that anticipation, and the imagination that sparks it. Some of those things reached your hands in ways that seem almost impossible. Everything took a long time. Everything. Before eBay we all spent a lot of time browsing flea markets, looking for hidden gems. You maybe found a book you had been looking for after long years, and you felt in heaven. But I’m sure you will agree with me: I’m also happy to be able to find some of the things I looked for years back and never found a lot more easily. [He smiles].

Talking about looking for things, you must have made an extenuating research effort to gather all the information for Here. I’m really bad at looking back to family memories, I always end up in tears.

Mmmm. Yes. Well, to me what’s strange is thinking that we all change, and then our relationship to these things changes as well. All those objects acquire different meanings. Things you didn’t consider important are, and vice-versa. It’s weird. When I started doing some research for the book, and once I had decided setting the story in the family house, I started looking through family history. On top of that we had just sold the house after my parents’ death, so I had to thoroughly review all the objects and photographs. It’s a curious process, reviving all your life through old photographs. Not only photographs: also letters, for example. That can be quite embarrassing. [Big laugh].

I’ve never been able to read the letters my dad used to send my mum during his military service, for instance. I would get a heart attack, I think.

[Big laugh] Exactly! But at the same time, I’m obsessed by that. I’ve written a diary since I was at high school, I’ve always considered writing whatever happened to me as a kind of mirror that helped me understanding things later (or right then), so I think having something like that is good. I still go back to the past quite often to revisit things. Patti Smith says she was quite happy to have written all those diaries because thanks to them she had been able to write Just Kids.

But doesn’t it break your heart? The years that will never return and all that. Childhood, teenage years…

I’m not sure. I know that it’s good to know where you come from, and remind yourself of it quite often. My family has always been very important to me and Here is my way of paying homage to that. At the beginning, to be honest, I was quite nervous. I wasn’t so sure about writing a book with all my family in it [he laughs]. But at the same time the book isn’t a memoir. It isn’t about that. Some things did happen, and others didn’t. While I was building it I kept on asking myself: “What am I writing about?” Because the book spans a colossal amount of time, and for that reason it needed an axis, and that is my house. But that’s just an instant, in fact. A fleeting instant. I’m trying to show something bigger than that house, that city, that country… In the book you see the creation of the planets, even the end of the world can be glimpsed on TV, as a little footnote. What encourages the book is more… How to say it?

Our insignificance?

That’s it. And it’s a kind of experience that teaches you humility. It doesn’t need to be depressing, but it makes you eat some humble pie: when you think about time in all its dimension. But you still need to be able to appreciate your own time. And know how to use it wisely, despite it being so short in cosmic terms [he laughs].

No matter if the dinosaurs became extinct or the ozone layer is disappearing, you’re still in the middle of an argument with your wife. It’s all about context.

[He laughs] Exactly. All those little things, things that are left undocumented, are as important as the huge ones. It all depends on the moment. A glass breaking is nothing, but it can have its importance, it can represent or explain a little drama.

¿Did you feel your hands tied to tell all the things as they really happened in the real house?

No. I took some liberties. I wasn’t even faithful to the physical aspect of the house. It isn’t an exact representation of the real living room. It’s more like a theatre version, like a set representing the house. I altered the placement of the window or the fireplace. If you saw a photograph of my old living room you wouldn’t find it so similar to the one on the comic book. Because what it was all about was treating some universal topics everyone could relate to. There are all those social rituals or events that mark and score time, like birthdays, deaths or weddings. These things mark the passing of time in a way we can all share and appreciate. So I made lists of that kind of topics that I wanted to cover and thought were universal.

I envy the fact that your mother was one of those people that kept everything. Mine was the opposite to a “hoarder”, I’m not sure there’s a medical term for this pathology. She tossed everything! Sometimes even things I was wearing at the time!

I don’t know, keeping everything can also be a terrible burden. I felt inclined to getting rid of much of that junk, although afterwards I felt guilty. I couldn’t stop repeating to myself: those things were important for my parents, yes, but for whom else will they be important? Do I really want to keep all this and give to my children for them to feel guilty as well when I die? [He laughs]. It’s a great burden. Today I’m trying to live in the most minimal way possible. I don’t want anybody to be burdened by anything. It isn’t worth it. But I do value some things. What I took from the family house were boxes full of photographs. And while I reviewed them one by one I realised that I didn’t know most people in them! [He laughs]. Once again: What do I do with all that? Why am I saving pictures of people I don’t know at all? [He laughs]. So now I’m trying to be realistic and I try to get rid of anything superfluous. Because we go through life carrying all sorts of stuff. It’s ridiculous. They’re just objects.

I’m reversing the family trend now, amassing all the useless junk I can so my children are face at my death with The Big Burden.

Let’s see. I’m happy my mum kept everything, don’t get me wrong. For instance, I have all my sketchbooks from when I was a kid, I like keeping that. But at the same time I don’t know what I’m going to do with that.

Well, for the moment you’ve already used them to create an amazing comic book. That’s something most people can’t say.

Of course. But at the same time, as I said, it isn’t a faithful family memory. Not to say that it’s more their house that my house. I spent there many significant years, but at the end what really happens is that we take the house with us. I’m convinced of that. It’s the idea of a home what’s important. I often dream with that house. A photojournalist insisted a while ago in taking me there to do a photo shoot, but I categorically refused. That’s no longer my house. It’s someone else’s. I don’t want to be photographed in someone else’s living room!

And it could even be considered trespassing.

[He laughs] Exactly. It’s better leaving it all as a sweet memory. As the idea of a home, and that’s it.

However, investigating the family tree is quite tempting. Our ancestors explain lots of things about us. I just finished re-reading Jerry Lee Lewis’ biography, and his fate was written in his blood. Did you discover amazing stories in the McGuire genealogy?

Well, it’s frustrating to realise that most of the findings of your research won’t fit in the final book. Because if I were to include it all, context, main theme and the book’s ultimate goal would be missed. I discovered mountains of facts, not only about my family, but also things such as the fact that Benjamin Franklin had lived at the other end of my street. It’s fascinating, yes, but the plot isn’t about Benjamin Franklin. I don’t want to give too many details about that coincidence. I only made him appear walking about the place that would end up becoming my living room. I found funny having Benjamin Franklin walking on the ground that would later on have the house on. In fact, Benjamin Franklin’s house, which in the book is far away and in one corner of the frame, was placed right before where my parents’ house would later stand, and it was huge. It would have taken the whole page. I had to diminish its importance.

I could talk to you about Franklin, and his son, for an hour. I also discovered really mad stories about the guy who was the town mayor, an eccentric and inventor who had designed the first steerable airship (that you could pilot, I mean). He travelled to New York with it and landed there with great pomp to meet Abraham Lincoln later on and tell him (overexcited) that his invention would help him win the Civil War: he should bombard the Confederates with his new airship. Lincoln thought he was bananas. That’s all great material, as you can see, but it would have forced the story in a direction which had nothing to do with what I imagined. Because my book is not about Lincoln or about big steerable airships. It’s about a breaking glass [he laughs].

Or someone choking in a sofa.

The choking scene did happen. To a cousin of mine. Completely ridiculous. Someone is telling a joke about dying, and one of the ones listening to it laughs so hard that he suffers a deadly heart attack. Don’t tell me!

It sounds like something out of Airplane!

Doesn’t it? When my cousin told me he too was rolling around laughing! I decided I had to include it at all costs. I feared it wouldn’t be too funny for the survivor relatives, but in the end they had all laughed with that anecdote before. It’s a comical situation, so I decided to keep it.

I read someone defining Liquid Liquid as “fun avant-garde” and I think that could be applied to Here. It suggests advanced and risky aesthetic paths, but it tells an entertaining story, it doesn’t fall into abstraction or inaccessible experiment for the sake of it.

I agree. I want all my works to be fun, and at the same time a bit avant-garde. Not too much. But I do want it to try and find new paths. Things aren’t completely interesting if they don’t try and explore new paths. And I think that Here has a bit of both things. When I was awarded the Golden price at the Angoulême festival two critics appeared on TV discussing both why should I and why shouldn’t I have received the award. Both disagreed on everything, except the fact that what I had done wasn’t a “comic book” [he laughs]. I wanted to tell them that to me “comic books” aren’t that sensational, that I’m not exactly a firm defendant of the term “graphic novel”. When it comes to me, I just had an idea and that seemed the best way to express it; nothing more. Call it the way you want it. Now I’m trying to produce a virtual reality version of my book using a 360º vision, and I’m very excited about it, because I won’t be able to use the panel system from the physical books, which means I will have to alter the conception of the work in itself. I like being in situations where I don’t know exactly what I’m doing, or whether I’m going to be able to achieve things. It’s the only way to grow as an artist.

I also read you once in an interview getting very excited about the concept “go weirder”. Before any creative doubt, go weirder! I love the idea.

It’s a great motto, and one that I personally subscribe. Lots of people told me that it was impossible for the new Here to be better than its first 6-page version, the one I published in RAW years back. The fear of not being able to surpass that kept me awake. Even mid process I kept on asking myself: “What am I doing? It was impossible to exceed that! It was perfect!” [he laughs]. But that panic was positive for me. You’ll only do it right if you’re scared. If you doubt. Then you know it’s worth it. Not when you go in autopilot through your comfort zone.

I think that as a creator you know something is going OK when you know what to leave out. What is extra, or shouldn’t be told, as we mentioned earlier. What’s just put in the story as an artistic fancy, or to sound funny.

Yes, sure. And even more: I was obsessed to insert some things that the book itself finally rejected. It spit them back to me. Because they didn’t fit in there at all. At the beginning I thought that a long narrative thread was going to be the answer for the book (after all I’m talking about the whole history of the world), but I ended up cutting it, and cutting it, and cutting it, because that slowed down the story too much.

There’s an anecdote about a Galician journalist, Julio Camba, who sent his editor an article much longer than usual apologising because he hadn’t had enough time.

I understand. The trick of comic books (and I’ve talked with many authors about it) is space economy. Going back to the text and keep on cutting until it’s no longer possible. Always cutting. Making it shorter. I admire that perspective. I read a lot of poetry while I was working on Here, and I think a certain desire of maintaining only the basics was filtered there. Going straight to the point with each sentence or image.

Even with sound. Penny Rimbaud from Crass said in an interview with Jon Savage that some great music genres –like punk rock, merseybeat or skiffle– share one feature: they leave a lot of free space.

Without a doubt. Oh, yes, yes [emphatic and nodding]. She’s right. You need that space. And you need pauses. I don’t know who was talking about pauses in songs the other day. The moment in which everything stops for a moment to start again. And I started compiling in my head a list of all the songs that stopped completely for a moment, and I realised that, as a resource, there’s nothing better [he laughs]. There’s nothing better than a John Cage moment. The moment of shutting up. A moment that grabs your soul.